Freddie McGregor ADD

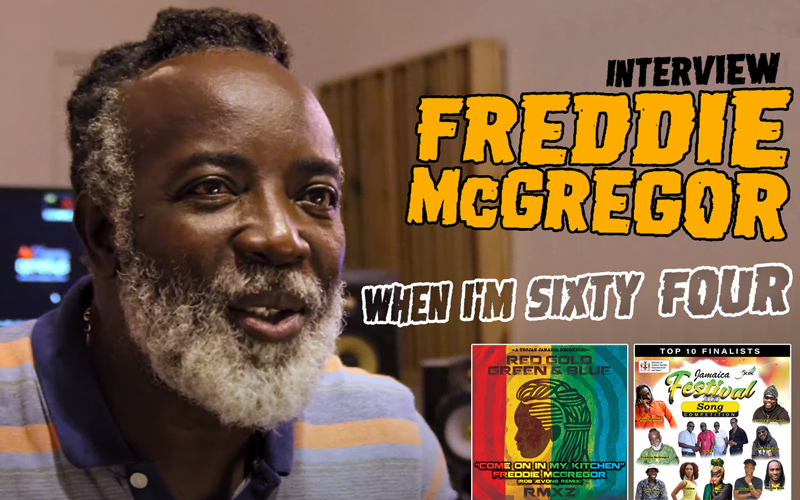

Freddie McGregor Interview - When I'm Sixty Four

07/08/2020 by Angus Taylor

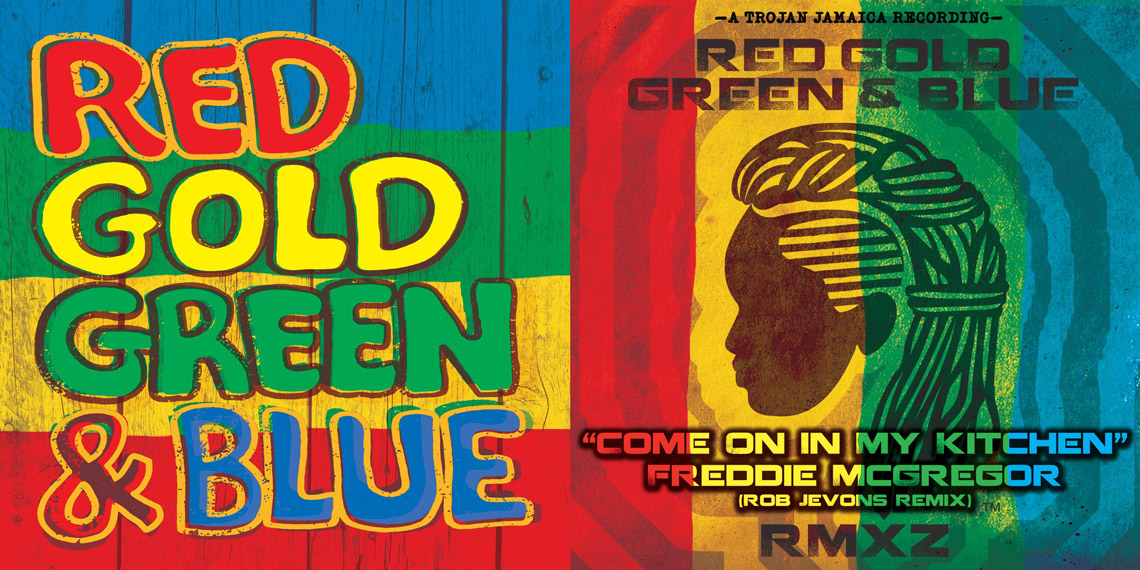

Lockdown has been busy for enduringly popular singer and Big Ship patriarch Freddie McGregor. He celebrated his 64th birthday with a star-studded streaming concert featuring Cat Coore, Christopher Martin, Dre Island and Naomi Cowan. He’s entered and reached the finals of the Jamaican Festival contest with his song Tun Up Di Sound. His cover of Robert Johnson’s Come On In My Kitchen, from 2019’s Trojan Jamaica album Red Gold Green & Blue, has been remixed by Rob Jevons. And he's been in the studio working on an unnamed new solo album, due next year.

Paul McCartney, a songwriter Freddie has covered more than once, sang humorously of being unwanted at the age of 64. Yet Freddie is as successful and loved as ever. Having started singing aged 7 in 1963, then joined the legendary Studio 1 records, he has amassed more hits than he can deliver in one setlist. And while his closest peers Gregory Isaacs, Dennis Brown and John Holt are no longer with us, Freddie’s Big Ship, crewed by his children Stephen, Chino and Shema, prows on.

Angus Taylor got a brief chance to chat with Freddie about some of his favourite underplayed tunes at Rototom Sunsplash 2016. This time they discussed broader, more emotional topics - past and present.

Freddie had lots to say on the Festival contest, his birthday concert and his forthcoming new album. He is proud to experiment and collaborate with the Red Gold Green & Blue project (co-produced by Zak Starkey, co-founder of Trojan Jamaica and son of Beatles drummer Ringo Starr). Simultaneously, he is driven by a desire for self-reliance, informed by his Rastafari principles.

Although he is modest about his abilities, Freddie is an all-round musician. As well as famously overdubbing drums on the rhythms that revived Studio 1 in the late 70s and early 80s, he plays bass, guitar and piano. Much of the history part of this interview concerns music and musicians above all else.

Freddie shares some poignant memories from his journey with the Clarendonians, Bob Andy, Dennis Brown, Earl Chinna Smith, Dalton Browne, Robbie Lyn, Stingray and Steely and Clevie. He also reveals a softer, caring side to producers Coxsone Dodd and Linval Thompson.

Can we go back to the very beginning? Can you tell me how you went from being a little boy singing in Clarendon to go into Studio One?

We lived in a community called Hayes. I learned there is also a place called Hayes in London near the Heathrow airport! Ernest Wilson lived around the corner from my house maybe less than a mile. Peter [Austin] lived in another community called Savanna. Less than a mile away. So we were basically in the same community. I used to go to Hayes Primary School and so did Ernest Wilson. Peter was a past student by then, but he also attended Hayes Primary School. We used to have singing concerts every Thursday after school and there was an acoustic piano. Ernest was fluent at playing piano, bass, guitar. So Ernest used to play every Thursday and I had to sing.

I made up a little song called Roll Dumpling Roll. “Roll dumpling roll, if you want to know how dumpling sweet, dip it in a coconut oil”. And word got out that there was a little boy who made up this dumpling song. I started to resonate in my community. Where I come from dumpling is a staple food for us youths. So in the evening time, coming from school we would see the people playing dominoes at the corner shop. And a man would shout out to me "Hey Tiny bwoy" - because my mum was called Miss Tiny. She was a teacher and was respected in our community - “Tiny bwoy, sing the dumpling song, let me hear it man!” (Laughs) And I would start busting (sings) "Roll dumpling roll, If you want to know how dumpling sweet, dip it in a coconut oil." But in a baby voice, you know?

And people used to give us thruppence, as it was pounds, shillings and pence back then. Some people used to give you a penny which was a lot of money then. So you and your friends had money to buy snow cone, ice cream. That in itself was a good vibe and made me excited. And as I grew up I started to think about how I would love to go away to foreign and sing for people. You'd close your eyes and imagine yourself abroad singing for people one day.

So one Thursday evening, Ernest’s mum, she worked at Vere Technical High School, came round to the house, and she and my mum were in a conversation. She was telling my mum that Ernest and Peter were going to Kingston the following Sunday for a recording session and that she didn't want them to leave me. Because I used to go by Ernest's house when they were rehearsing and usually as a little kid when those people are rehearsing you would dip in.

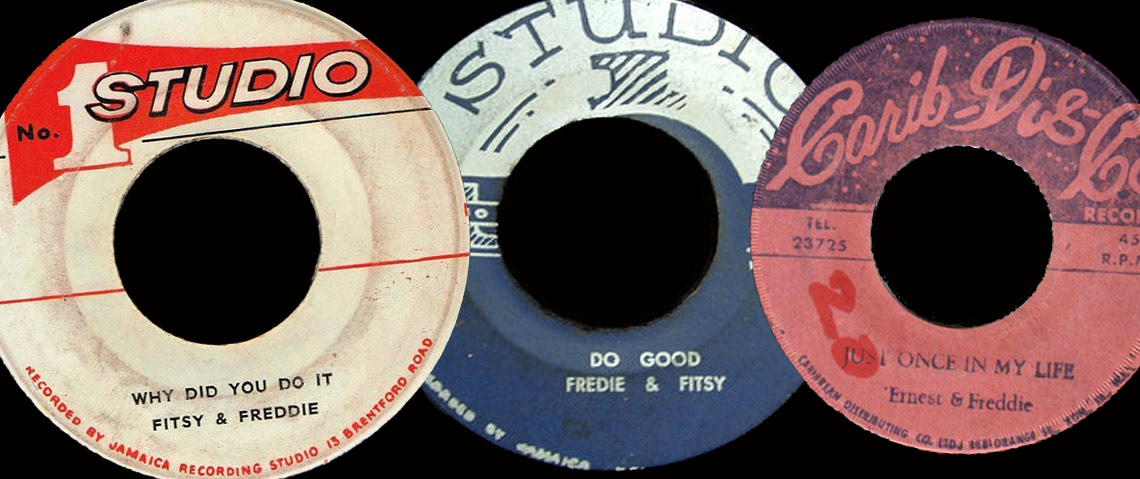

And then that Sunday came and we went to Kingston. We ended up at Coxsone Studio 1, 13 Brentford Road. And the rest was history. When we walked into the studio that Sunday there was a long line to begin with at the studio gate because people were there for audition. And we walked in because Ernest and Peter were already so famous, they had songs like Shoo Be Do, Can't Be Happy, Rude Boy Gone A Jail. I wasn't really a member of the Clarendonians group as most people think. But then they brought me into Kingston and everybody had me as Ernest's little brother. And because we started to sing everybody just associated me with the Clarendonians. However, there is a song on the Clarendonians album called Do Good And Good Will Follow You, sung by myself and Ernest Wilson solo. Peter Austin did not sing on that song. It came out on 7 inch as Fitzy and Freddie on either Coxsone or Studio 1 label.

Who did you audition for? Did you audition for Mr Dodd himself?

I didn't have to audition!

You just passed the line because if the Clarendonians said “This boy is good” then this boy is good?

Ernest and Peter were famous, so he's good. So when we walked through the gate there were just crazy high praises for Ernest and Peter because at the time those two were busting up the place. Rude Boy Gone A Jail, Shoo Be Do, Can't Be Happy, just a bunch of hit songs. So that Sunday everybody was excited, all the musicians were shouting out to them, greeting them. And everybody was saying "Oh, your little brother this?" And they said "Yeah man, little Freddie, he can sing you know? Sing your dumpling song and make them hear." And immediately I had to bust the dumpling tune because I wasn't shy like that. So everybody got excited “Whoa you can sing little baby bwoy” and I guess I was in! At the moment that I came, I got in.

And then later on I got introduced to Mr Dodd. And the same thing happened. Because by this time all the musicians were telling Mr Dodd “Little Freddie, him can sing!” And Ernest said “Sing your dumpling song, make Mr Dodd hear”. And I bust Roll Dumpling Roll as a little baby and it was pure excitement again. So I guess I was in with Mr Dodd at that point. And I was there for like two days. I lived in McGregor Gully out east, Rollington Town, with Ernest's aunt. That's where me and Ernest stayed. It was ironic because my name is McGregor and the first place I lived was McGregor Gully! And after about two days Mr Dodd asked Ernest where I was staying and Ernest told him.

I'll tell you something, I love Mr Dodd, you hear? I truly love that gentleman. Mr Dodd looked at us and said “When you come in tomorrow, bring your stuff”. I had no idea what was being planned. So Ernest brought my bag the following day to the studio. And that was the last day Ernest and I lived together. Because Mr Dodd took me to his house to live. With Mrs Dodd, his three daughters and his son. I ended up living in Pembroke Hall with Mr Dodd. The first time I saw a living room chair. The first time I saw a fridge. The first time I saw a lot of stuff. It was Kingston and that was a real, what you call, an upper class neighbourhood back then. And that's where I stayed going forward. My mother used to come up every month and come look for me. And Mr Dodd would always make sure she had money. Mrs Dodd taught me everything. How to use the knife, the fork, she taught me everything. I became her little son.

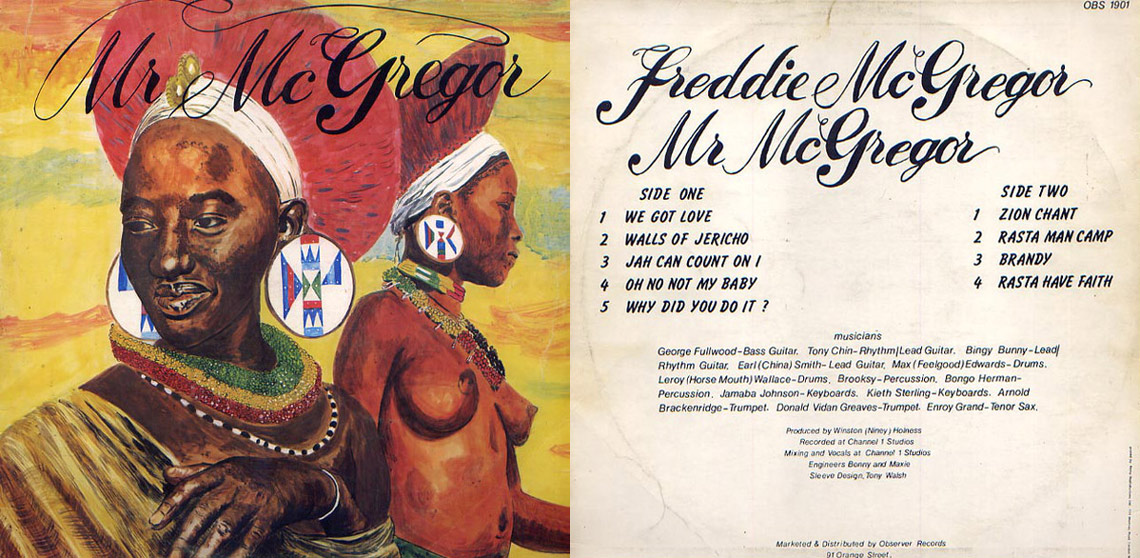

Looking back at it now, for someone to do that, that person had to have a great heart and at least had to see something in you to want to take a chance with it. Later on he boarded me out with a Christian family and sent me to a Junior High School on Hagley Park Road. Ernest and I went to that school together. And we just continued on our journey and our main thing was studio - every chance we get, studio. After my schooling stopped at that school I didn't go back to any other school. The rest of my schooling was 13 Brentford Road. And that is where I stayed from 1963 to 1979, when I did my first project outside of Studio 1 with Niney Holness. We made the album called Mr McGregor.

One of your favourite albums to listen to is Bob Andy's Songbook. I guess you met Bob Andy at Studio 1?

He was there when I got there that first Sunday. He was one of the persons doing the auditions. Him and BB Seaton from the Gaylads, Tony Gregory and Bob Andy. And there were people lined up outside. That happened every Sunday. And by then I became friends with all those people because I was like Mr Dodd's little son at the studio now. I could get the chance to be in the studio when sessions were happening. So I learned everything that I know today. That's the best university that I went to. Because I hadn't gone to school other than what I told you earlier. So everything else I know today I just learned.

I learned a lot from Mr Dodd. As I stayed there and I watched him struggle I saw our struggle. As he struggled, we struggled also. So I could relate to his struggles. And then when I went off and started my own studio I started to experience the same struggles. And I recognised even more what he was going through. But it was a great experience. And one that I'm most thankful for. Mr Dodd gave me a name “Freddie McGregor” that I can live by today. Because that is all I needed. He didn't have to do anything else for me. He did all he could. He did the greatest thing for me. And I love Mr Dodd. He's my father. He's my daddy. He's my mentor. I look up to him so much. And I miss him.

That really shows such a caring side to Mr Dodd.

Yeah man. The man is great, man. He's done so much for so many of us. So we should really be thankful in our hearts. Because for every good people do for you, you have to be thankful for it. He didn't have to do anything but he did it. What a great heart. I love Mr Dodd and I say that loud and clear always.

Can you tell me about how you learned the drums? I heard it was in the early 70s when you were touring with Generation Gap as a dance band?

Well I started learning the drums before that. Because being at Studio 1, whenever Horsemouth or whoever the drummer was, took a break, I got the opportunity to go in and fool around. Once Jackie [Mittoo] walked off the piano and they went for lunch I would fool around on the piano and start banging something. Because in there watching them every day it was like learning to drive a car. If you start watching your daddy drive every day, looking at how he moves the gear stick, how he puts his foot down and how to change gear, you'd say to yourself “I can do that”. Until you get the chance to physically do it. You know you can do it. I used to watch everybody play and tell myself “I could do that” so when they took a lunch break, I'd always go over to the instruments and fool around. When you’d hear the door screech, you'd know they were coming back and you just go in your little corner and be silent again. That's when I learned to play drums and stuff like that.

But when I joined Generation Gap, I was the lead singer. Then one New Year's Eve night we happened to have a concert in St Elizabeth. Horsemouth was our drummer then and we took a break at about 11. We had to go back on at about midnight. And Horsemouth found some friends on the beach, it was in Treasure Beach, and took a boat with them to go to Sav La Mar to find some weed. So at 11:55 the band was ready to go on - no drummer. Everybody getting anxious and excited, people started to clap because we had to ring in the New Year.

So there was one alternative now. To put the mic in the booth and turn it to me. So I was going round to the drumset and I wasn't sure how this was going to happen! But every night I performed the songs so I had a feel, in terms of being a musician, of what the songs are. So I tried and it worked out. And everybody was super excited. For a while they had me doing it and doing it as if I was going to become the drummer and the lead singer. I had to protest quietly and they eventually got another drummer and I got back to the vocals.

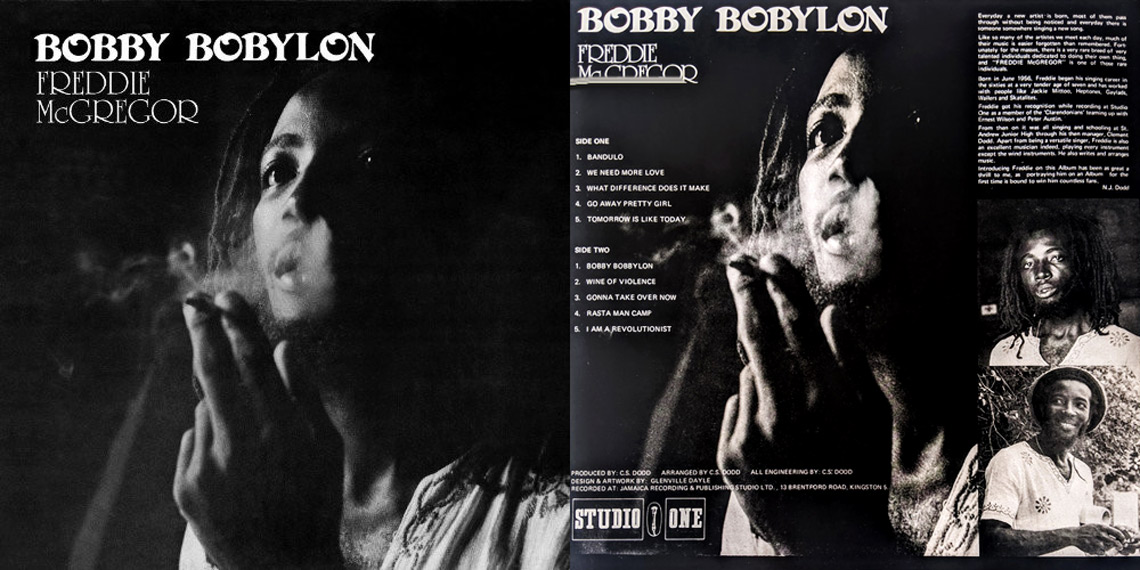

But in the same way that's how I played around with the piano and the guitars. I taught myself everything I know musically. I wish I went to a music school. But my parents never had it like that and I never had the opportunity. I was too caught up trying to find a hit song at Studio 1. And it was when Bobby Babylon came that I got my real break. And then I told myself that “once the Lord blessed me with one song that's all I want. I will find the rest for myself. Just give me one”. And he did give me one. Bobby Babylon. And that's all I needed. From there I would take care of the rest of it. And I've recorded many songs since Bobby Babylon. Many hit songs. I'm just fortunate to be here still doing what I do best.

Was Studio 1 where you met your musical director Dalton Browne and another favourite producer Clevie Browne? I know Clevie was in the Studio 1 band.

Actually I met Dalton when I joined Generation Gap in 1970 or ’71. We met then and we formed a band because Dalton is a truly talented person. We always had the same musical vibes so we stuck together. Even when the band broke up I just decided “Dalton wherever I go, you go”. And if you notice, over many years, as many years as you can think of, you'll never see me without Dalton Browne. Rarely ever. We work together like that. From our boyhood days until today.

Clevie, same thing. Clevie was a member of the Studio 1 band which all of us were part of. And it was out of the Studio 1 band that Steely and Clevie was created. Because Clevie was our drummer and then one day he brought Steely along to play, along with Pablove Black as our keyboard players. That's where Steely and Clevie really hooked up. And at the end of the tour, Clevie bought a drum machine. And after he bought that drum machine, Steely bought a keyboard and they went back to Jamaica and they started to do stuff. And that turned out to be Steely and Clevie.

And then later you and Steely and Clevie would do some of your most popular songs, mainly cover versions, in the early 90s.

And they got a great run. And we miss Steely so much because Steely was just a talented musician who was self-taught also. That's the genius with all of us, we are all self-taught so they really have to love music to get into it the way they did. And we would just meld and gel when we created stuff together. We’d look at each other and we’d laugh and it was just a magic moment. And that's how we do it. We never do it any other way.

Can you tell me about working with Soul Syndicate guitarist and producer Earl Chinna Smith from the mid 70s? This was while you were still at Studio 1 and around the time Rasta had come to you. You recorded some of my favourite songs with him.

Chinna is another source of inspiration for me personally. It was about in 1975. I knew him before that but ’75 was when we hooked up. That was after Generation Gap had started to phase out a little. I met Chinna and he said “We rehearse at Delamere Avenue and when you have the time man, you can always pass through and sit in and hold a vibe with we”. And I liked Chinna you know? Chinna was so musical and always an inspiration. I started going by the rehearsal and I hooked up with Tony Chin, Fully Fullwood and Max Edwards and the whole Soul Syndicate team. And we started to jam and eventually started to record. That's how I recorded that album in 1979 for Niney.

And when I started to rehearse with Chinna, he introduced me to a tour that was coming up in 1975 with Soul Syndicate. They had just lost their lead vocalist, a brother by the name of Donovan [Carless]. So Chinna urged me to come and I did and that was a great move in 1975. We ended up in Boston where we rented a house for a month and that's where we stayed and we did gigs all over the country from that point. It was a great tour and a great experience for me too.

Chinna was the kind of person who would carry some way-out music for me to listen to! That's the thing I liked about Chinna the most. Chinna was the first person who turned me on to a group named Steely Dan. I listened to their tracks and I was freaked out. We used to listen to this group Earth Wind And Fire. And while we were in Boston, Earth Wind And Fire had a concert in Providence, Rhode Island. We all went to that concert that night - amazing! I will never, for as long as I live, forget that concert. I saw Earth Wind And Fire with Maurice White, Philip Bailey and the entire original group. We even signed a copy of Soul Syndicate Harvest Uptown album and gave it to Maurice White that night. It was magical. I've never seen anything like it before. And I've not seen anything like it after. Just magic, can't explain.

That's how my interest in soul music started to build. Chinna saw that I loved it and he started introducing me to some way-out music. We built a great relationship. And while doing so we started to look at songs and we looked at Love Ballad.

George Benson.

I heard Chinna playing it one day and I started singing the line and didn't know the words. Chinna said “Yo, we could record that song. It's a bad tune”. I heard him playing Natural Collie which was My Starship. I don't think a lot of people know that that song is actually My Starship by Norman Connors. Chinna brought me the rhythm track he did and said “Yo, you can write a nice song to this”. And I just came up with a melody using the bassline. (sings) “Being down in the valley, smoking natural collie, getting inspiration, spreading it to the nation”. But the way I ended up creating the melody, Norman Connors couldn't recognise the song. It would have been very hard to recognise that it was even My Starship.

Chris Blackwell at the time became very interested in the song and wanted to release it. He thought it was a hit. Chinna and I had to tell him that it was actually a cover of My Starship. Then he had to send it out to the publisher for approval. And then the guy Connors said he didn't smoke and he didn't use drugs and he didn't want the song covered. So the song didn't get the treatment that it would have gotten. Some people do smoke weed, some people don't. I can understand that.

I want to ask about one lesser known 45 you did with Chinna that I missed at our last interview at Rototom. As well as Mark Of The Beast and Sergeant Brown you did some wonderful covers like Mission Impossible but also a version of John Holt Strange Things with crazy backing vocals.

How you know those songs? (Sings) “What the hell is going on?” You see what it was? Soul Syndicate at the time with Chinna, we were like an Earth Wind And Fire, you know? That's how we felt. We felt like we could create anything. We felt like we understood what they were doing and we could go to places that they don't think we could in terms of music. That was the whole thing about that era. We were searching for stuff. Like when we came up with the song All In The Same Boat, it was the same influence. I was like “No man we could create stuff. We're outstanding”. You just have to go inside of your brain and just find it. And those were happy times because we were truly creative with great musicians around us. It was hard to do anything wrong during that era.

What was the first song that you produced for yourself and what was the first material you produced for another artist?

Well, that's a good question. And I would answer it this way. In our early years a lot of the work we did, we were actually the producers without knowing. We gave credit to the executive producer who was the person who would pay for the studio time and get us to do the session. But we were always the ones who produced the tracks because they weren't in the studio. When the musicians were ready, they would say “So Freddie what are we doing today?” So because you would have to decide what you are doing, not the producer, I would just go around the piano “Alright, this is the track we're going to do. F Major 7, G Minor” (sings intro to Big Ship). And that became Big Ship.

I was just going to ask you about that song. Flabba Holt told me that song got recorded when everyone was packing up after the session had officially ended. Scientist told me Linval wasn't in studio much for Channel One sessions.

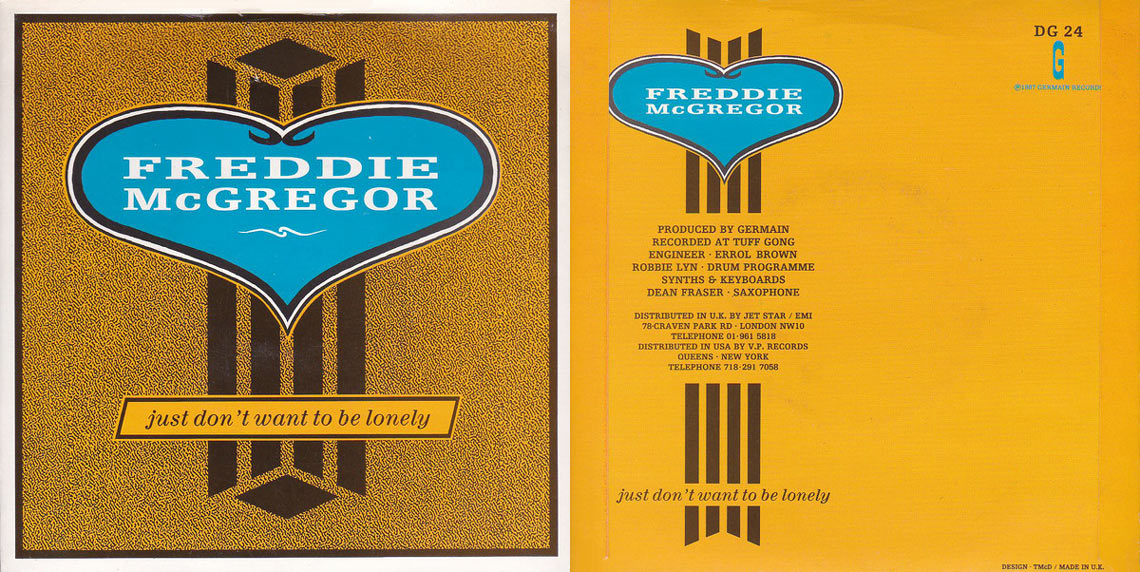

Back then, a lot of that happened with people like Niney, Germain, enough people. Because what producers usually do is book the studio time, bring the tape and put the tape in the machine and then they're gone about their other business. They only return when the song is complete. And listen to a nice song and get the credit as producers when we actually do the work. Just Don't Want To Be Lonely was the same. Donovan didn't produce that song. It was myself and Robbie Lyn. We produced the song. Robbie Lyn worked out the chord arrangement, I gave him the bassline, he programmed the drums and… history. Just Don't Want To Be Lonely. Germain only heard the song when he came back in the studio to listen.

And stuff like that happens along the way, a lot of people get the credit but we never feel a way over that because we didn't even understand it. We were just excited in making some wicked tunes. So it all worked out well and great and we're able to move on and still have friendships. Linval and I are still so close. He just came and looked for me the other evening and I was really longing to see him too, you know? We went to Bobby Digital house’s when he passed on. Some of the rhythm tracks, Linval made them for different things and I just happened to write great songs on some of them. And I didn't hesitate to share the publishing with Linval. And every song on that album, Big Ship, we went half and half. Linval is a great spirit, a great producer, a great brother with a great soul. He shared the record with me and I shared the publishing with him. And that's how we move, as brothers.

Again, another side to Linval. Can you tell me about the writing of Push Come To Shove in 1986?

Well, I was signed to RAS Records at the time. I was going back and forth to Washington DC a lot. Air Jamaica had a flight from Baltimore to Kingston. I boarded the flight and was sitting at a window seat which is how I always prefer to fly. I always wanted to write a song about the airport because we were travelling so much back then. I just sat there in my seat and had my boarding pass, looking through the window thinking “Yeah, I'm going to write a song about flying and ting”.

And then the idea came “I'm longing to see you, I want to know how you've been doing over yonder”. It just started that way and I kept writing on the boarding pass “I'm going to catch this flight, I'm going to reach my destination, I hope you'll be smiling, longing to see me, and then keep thinking, thinking thought you drop me a line, just to say ‘Hello my dear I've been fine’, but it doesn't matter anyway because my love for you will never change”. And I wanted to use a hook that people would relate to. I ran through some things that old people would say “When push come to shove everybody wants to put the blame on me”. Because old people always used that saying in Jamaica. Little did I know it would resonate.

What about the rhythm? Was it an existing rhythm? I've heard that it was based on one of your songs at Studio 1, I Don't Know. But listening to it, it's hard to make out.

Well it wasn't existing. What I did was, I had the song, called I Don’t Know, which I recorded for Studio 1. It's on the Horace Andy Just Say Who. So I basically pinched a piece of I Don’t Know but used my creativity. I used a different bassline, I created an entirely different horn section. The only thing still there is the chord progression. But other than that I just fitted a bunch of ideas and arrangements around it. I wanted the song to have a jazz feel and that's why I created the horn section the way I did. Like I said, in those times the creative juices flowed. I was trying to create things that others would be impressed with as Jamaican youths.

Did your experiences with Polydor and the Freddie McGregor album lead you to want to set up your own label or have you always had that in mind?

I always had it in mind but that experience definitely fuelled a quick movement of setting up my label. Because coming from Studio 1 again and the struggles that we witnessed, everybody wanted to do something for themselves. And growing up around Bob [Marley] he always would say that too. If you had a conversation with Bob when he was around then he always aspired to have his own thing. "Man should get their own thing and make we own thing". And even myself, when I started to record and I did some songs I said to myself “Why didn't I have this song on my own tape?” As opposed to all them other people's tapes. So those things really spurred me forward to set up my own thing.

We talked about Dalton and Clevie but another producer who you work with a lot is Stingray in England.

Well, Stingray is family. Blood family. McLeod, McGregor, we have that link. So I love working with Dillie. Dillie has one of the best vibes as a producer. How can I put it now? Dillie knows my style. He knows the flavour. He knows what I like. So whenever I go to England I always look forward to going to the studio and sit down for most of the day with just ourselves. Vocalwise. “Dillie what you have?” And he'll say “Man! I have some things man”. And we'll go round the studio and Dillie will have a way to come up with some of the craziest tracks. And when I hear a track that is crazy I get crazy too. So I have to find a big tune for that track. And that's the combination we have. Always, always. Right now I have this track that I just finished for Dillie. This is going to be on my new album. Bad bad bad bad bad - and I smile because that's Dillie! Always has the right tracks for me.

When you did your Di Captain album in 2013, celebrating your 50 years in music, you covered The Beatles You Won't See Me which is a tune that the Clarendonians did back in the day.

(Big laugh) Yeah that's a song I always loved. And I wanted to kind of give back some shine to Ernest you know? Because people would remember that that was done by Clarendonians. So we chose that song. And yeah, I love the song man. “When I call you up, your line's engaged”. It's a beautiful song.

Let's talk about the remix of Red Gold Green & Blue that you did last year for Trojan Jamaica. Your reggae cover version of Robert Johnson Come On In My Kitchen has a much more bluesy sound. The history of blues and Jamaican music are intertwined. Dr Carlos Malcolm told me that New Orleans blues came to Jamaica with Us soldiers during the second world war, and that was influential in the birth of ska.

Well, I am certain there is a strong link there. Blues was a little, I would say maybe before my time. I came through in 1963. I enjoyed the ending of ska. If you listen to some of my first recordings they are ska. But that was the ending of ska. There was a track called After Laughter.

The Wendy Rene cover that you did as Little Freddie.

And a song called I'm Too Young To Love. Those were songs when I was a little baby boy like 7 plus. So you can hear the rhythm tracks. They are ska. But it was towards the ending of ska. Because earlier ska, they were fast. But as we faded out in the 60s it became slower. And then it became so slow that it ended up becoming rocksteady. Courtesy of Lynn Taitt, Carlos Malcolm, all of those great people like Ernie Ranglin of course. And then it evolved into what we call reggae after rocksteady and then it just continued into dancehall and we're here.

But the album, I wasn't familiar with some of the tracks when it was introduced to me. But I always like challenges and I love music so it doesn't matter. I love Zak’s vibe. That's what draws me to the project. We had done a concert for Peter Tosh a month or so before. And I really admired him because I knew about him and wanted to hear him play. Because he's a wild drummer. I've never heard him play the drums yet. But I saw him play guitar and it's really crazy. I was drawn by that and we got a chance to meet and I was introduced to the project. I immediately said “Yes” because we're always excited to try new things. Because one never knows what will come out of it.

So we went up to Ocho Rios for the recording session and it was a great vibe. We had Sly, Horsemouth, Tony Chin, so many musicians there. We went through the tracks one by one and when I recorded that song about In My Kitchen, I found it funny! (Laughing) I really like the song. I went back and looked at the original. That's a wicked singer! But I wanted to put my spin to it and it turned out the way it did. I really love that project. I certainly hope that project will do very well.

Your legacy continues in your children. Stephen even recorded your Roll Dumpling Roll song with Tiger. You must be very proud of them and what they achieved.

I am indeed. I wish everybody never chose music but… (laughs) yes I am. The music thing is difficult, you know? To be honest with you. I love it. I thank God that he chose me for this. Because I understand today why he chose me, the reason why I left country and what he wanted me to do.

My whole journey was about my parents though. Let me get back to that first. Looking back now I know what my journey was all about. Because as a youth I used to wonder how my mother can survive. Because where we come from there's no industry. My father worked in the sugarcane industry to take care of so many children. His heart was real big, man. So from an early age I'm thinking “Bwoy, I'd love to do something for my mother so she can't struggle all the days of her life like that.” That was one of the things that drew me to go to Kingston. Because at 7 years old no little average youth gets to go to Kingston. They're supposed to be with their parents. That's how I recognise now what my whole calling was. And I'm glad it worked that way.

I never really wanted my youth necessarily to be musicians. That kind of life is too hard and difficult, man. And nothing is guaranteed. But just seeing my kids grow up around me and then seeing that you love what you do, oftentimes it ends up that way. Stephen did love the music bad. And from an early age he did go for it. And then when we built the studio he became more excited. Then after a while we realised this is what he really wants to do. And look at him today. One of the better producers. And I'm proud of him and I'm glad for him, man.

Chino is a bad bad bad musician. Witty, great writer too. And I have my daughter too, Shema. She sings with Wailers and lots of other things. And they are doing what they are doing. So we'll just build another studio so that everybody can get a chance to do their thing when they want to. I think that is one of the most important things. That we are able to do what we want to do when we want to. Because we can do it on our own.

How are you dealing with the lockdown quarantine situation? Have you been farming? Have you managed to do the things that you love doing outside of music?

I'm good, I'm hanging in there, fighting this Covid thing. Yes, I've got a chance to do some of that. Not as much as I would want to. Because musically we are really busy, in the studio working on a new album. But we're not rushing because this album is for next year. We are working on tracks and so you spend time on that, on planting food on the farm and taking care of the horses.

Who are you working with on the new album? You mentioned Dillie. Are you working with Dalton and Clevie again?

Yes. Plus more. Dalton and Clevie, those are my main producers I work with. But yes we work with a lot of people like Kirkledove the drummer, Mark, who is Shaggy's drummer, Robbie Lyn, my bass player, a bunch of different people. Because we're trying to sort this record out and get a different vibe, different feel from different people that we believe in musically.

Do you have a title yet?

No, we're just recording. We just record tune. We also have a Gussie Clarke, some outstanding rhythm. I can't wait to approach that one too. So this album is going to be diverse and that is something I look forward to. I have a new single with Romeich that's called Bawling and that is definitely going to be on the album. It might even become the title track. Because that song is going very hard. I have a single out called If God Is For Us. I think that song should end up on the album. I have a song that came out earlier last year called Go Freddie Go. Those songs will be revisited. But we don't know what's going to happen. We're just recording. We just laid eight new rhythm tracks that I haven't even started writing for yet. So we're good. We just want to be early out of the gate. So when things clear up we are ahead and not “trying to get ahead”.

Can I also say happy birthday? Did you enjoy the streamed concert last weekend? How was it logistically putting something together like that compared to a normal stage show?

(Laughs) Yes sir! Thank you! We all did enjoy that. The logistics is fine. We have people here we approach and that was the easiest part. But to buck up the stream is really the more difficult part. To make sure the signal is fine. You need adequate Wi-Fi for that. And we had all of that in place so no, nothing was an issue as it relates to us getting it done.

You did a tribute to Dennis Brown, who you’ve said is one of your favourite singers. You must have known Dennis well. You recorded with him with Gussie Clarke. You've appeared on memorable stage shows with him like Sunsplash in Jamaica, and on Clapham Common. What are your memories of him?

Dennis is my brother. Dennis Brown and Gregory Isaacs are my brothers. I love them. I think those are the two closest people to myself in music. We always had a great vibe. A great friendship. We’d talk to each other a lot. We'd link up a lot. We’d hang together a lot. We'd tour a lot. Those are two persons that I admire greatly. Love them. As a brother and as a family. So it's always easy for me to sing Dennis Brown. And sometimes get into Gregory. Dennis and I, we had that relationship. There wasn't a Reggae Sunsplash that Dennis wouldn't call all myself, Gregory, and John Holt back on stage in the morning for what we call the Morning Ride. That became a signature moment at Sunsplash, because every year all of us would be on Sunsplash. Everybody would look forward to when the sun comes up, Dennis Brown would be on stage and call his brothers up and we'd go on to just wreck the place!

You’re also a finalist in the JCDC’s 2020 Festival Song contest, with Buju Banton, Papa Michigan, Shuga, LUST and another man from Clarendon, the original 1966 contest winner, Toots.

(Big laugh) Alright, firstly I never saw myself as entering a Festival song. The furthest thing from my mind. It's something I enjoyed. Back in the day when Toots won with Bam Bam and Tommy Cowan and Desmond Dekker and all those great artists, that's when I was quite interested in it. It was something everybody looked forward to. You wouldn't want to miss the Festival back then. I think things have changed as the years went on. I think Cherry Oh Baby may have been the last really big proper Festival song that turned out to be a big international hit. Because Eric Donaldson nailed it. After that people started to lose interest in Festival. Roy Rayon was one of the later stars of the Festival era. But then that started to fade. People just started to forget about Festival.

But Festival is really a part of Jamaica's cultural heritage. And the last couple of years it hasn't been interesting. The writing ability waned a bit. So the Minister of Culture, she actually asked us if we could help her, try and build back the writing skills of the festival song competition. She asked if we could either write the song and get someone to perform them. Or if we could write and perform the song it would even be better for her. I was kind of shocked when she asked because I didn't know who else was asked either. But as a patriotic Jamaican with my involvement with the music industry it was hard for me to say no to her. Because it's not about pride. When things like this happen, it's not about pride. And I don't want to be called a Festival singer or anything like that. At the moment my thought was “We need to do this for Jamaica. We need to do this for the country”.

So I said “Minister, yes. I will write a song and I will get someone to perform it”. And she hinted like “Well if you could perform it then it would be even nicer” and I laughed! So when we got the song done I was thinking “Who could I get to do this song?” And I couldn't immediately think of anyone who would do the song quite the way we wanted it. And we had a short time period in getting it to her. So I did a demo track on it and I sent it to her and I told her it wasn't completed but I wanted her to get a feel of what it was. And she said “Beautiful vocal, beautiful melody - this is a BAM! I suspect you are going to sing the song”. And at that point I said “You know what? Let me just do the song”.

And so we re-voiced it and it is what it is. Tun Up Di Sound. Originally my title was Jamaican Paradise. But when they announced the finals another artist had a song with the Jamaica Paradise stuff. So I just immediately changed the title to using the chorus of the song Tun Up Di Sound. I wanted to write, not just a Festival song but a song that could last past Festival. Because that's what she asked us to do - get out of that box and create something more international.

So when I heard that Buju and Toots and Michigan were in I started to get nervous! “What the heck is this? I'm in competition with these people? That's not what I wanted”. But then also I understood. Because I was the one who introduced LUST to the Festival to be honest with you. We were at Mixing Lab doing a session where LUST and I were recording a cover of George Michael Careless Whisper. I told Lukie I just sent in a Festival song. He got excited. He said if he had known, he had a song that he would definitely have sent in. I told him “You might still have a chance because the deadline should be today or tomorrow”. So we made a call and we were told that we could send the track because he was just right at the deadline. And it ended up in the final 10.

After I made it to the final 10, I became excited. Because at that point I understood that I was doing this for my country. Not to win the Festival song competition or to compete with my peers but to create a nice song as my contribution to the Festival. I haven't heard the Buju song in completeness. I heard LUST’s song because Lukie had played it for me at the studio that day. I hope she has 10 strong songs that could sell that CD. And whoever wins the Festival song competition, really “Well done”. I think at the end of the day it's not going to be who is the most popular. I think it is going to be the song that everybody wants to sing. I think that's what it will boil down to. And I want to stress that “May the very best song win”.

I want to say one last thing. When you're on stage everyone can see you're singing your heart out but you move in a very relaxed way. Like a big ship through the ocean. You can tell you work very hard in your career. But you never make it look like you're straining.

(Laughs) Rocking and rolling! Yes, and you know why? Because that allows me to preserve me. So I can continue on. Because if you strain yourself through a career of so many years it's bound to affect you. So you have to recognise that for longevity you want to try and be as comfortable as you can, doing what you do. And put less strain on your body. But it's a rough road I can tell you! Because to stand up on the stage for 2-hours and sing so many songs there ain't nothing easy about that! Sometimes I wish I was plugged in like a guitar amplifier! But that's not the case so I have to do what I have to do.