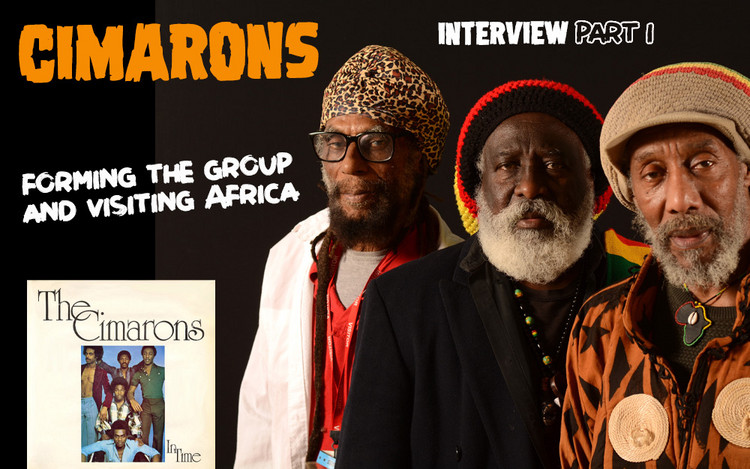

Delroy Washington ADD

Delroy Washington Interview (2012) Part IV - Community Activist

05/26/2020 by Angus Taylor

In the final installment of our 4 part interview with Delroy Washington, Delroy speaks about his work as a mentor and community activist. He also explains why he wasn’t involved in Kevin MacDonald’s 2012 film Marley and how it could have been improved.

It’s striking, looking back, how some of his ideas from eight years ago were ahead of their time. His thoughts on Rastafari and meditation are reflected in the lyrics of 21st century Jamaican artists such as Jah9 and Kabaka Pyramid. North West London’s reggae culture is currently being celebrated by the borough of Brent’s No Bass Like Home project.

Some reggae histories have suggested that you faded from view after you left Virgin. In fact you’ve been extremely busy with many community initiatives...

One of the first things I did was set up a service back in the day in Ladbroke Grove for musicians who were having a hard time that didn't know the business. And I can tell you - the amount of people that got helped through that. Jackie Mittoo who was somebody who is like a mentor to me that got helped. I sat down with him. In fact it was more than just a musical service. It was also a spiritual type service. Because people always wanted to come and talk to Delroy about Rastafari and how I live and things like that. So it was kind of like a surgery in the sense, as opposed to it being an office. Because my place was always open to the youths.

In the next few months we're going to be doing some stuff at a club called the Heritage Inn down here. Some of the things that we used to have in Ladbroke Grove. Because I went to a funeral down there and people were saying “Boy, Delroy you shouldn't have moved out of the area”. Because what we had down there was like a surgery. It wasn't just for reggae musicians. It was for anybody.

It didn't matter what colour you were from my perspective. I am one of three founder members of Twelve Tribes in this country. And Twelve Tribes has never been about the colour of your skin and what you look like. Which some people used to have an issue about until they come into Twelve Tribes and see how we function as people. We're not functioning as black people or white people. We’re functioning as Rastafari people. Of all colours and shades. When you go to Twelve Tribes in Jamaica you see from the blackest or darkest colour coming right through the spectrum to the whitest looking person. Some people might not like it. For me it's fantastic. It shows that people can get on together if they really want to, if we share a common interest. And all of what I was doing was based off a Twelve Tribes principle. His Imperial Majesty and the things that His Imperial Majesty talks about.

I'm into Buddhism. I read Buddhism. I love Buddhism. I've read all of the Vedantic scriptures. So I moulded my spirit as a combination. Just like my music it's a combination of all those different influences. So the things I've been doing are based on what I believe. We need some money to do things but it's not really money that does things. It's people that do things. Because once you've got money you still have to live and do what you have to do.

My thing is young people who lost their way and we help to guide them. This is one of the services I provide. If you go outside here you'll see them. There are scores of young people. I had problems as a young person growing up in this country. Because of ignorance. In my camp when we were at Ladbroke Grove, you're talking about little black kids, little Moroccan kids, little Somalian kids. All of those people were part of my thing.

The little white kids who seem to be dropouts from where they are. People like Frank, he's still around me (laughs) and he's probably been around me longer than most black kids. 35 years from when he was a kid. People like Penny Reel. Penny Reel was part of our crew. He was somebody that was maybe seen as a dropout among his people. Penny Reel came amongst us and got accepted. We never treated him differently. He came down and ate Ital food with us the same way. So our thing was a communal thing that talks about unity and love and trying to bring people together to live closer together. So was Tony and I at Addis Ababa studio which was something that I helped to finance. Look at all the people who come out of it. Soul II Soul.

When did Addis Ababa studio start?

Tony [Addis] started the studio around 1979 or 1980. It was actually an 8-track studio. A little girl, a friend of mine called Barbara, Jamaican Indian, was having problems with the studio. She used to be friends with Tony's girlfriend. She was running into financial problems with the 8-track so she gave him some money and said “Right, sort it out”. Tony came and I started helping him. Tony will tell you I never went in there and said “I want this, I want that”. I would just bring somebody there and introduce them to the situation and things got done. It was to help local people who wanted to get a little break. That's been my life. We're talking about being a humanitarian Rastafarian! (laughs) Soul II Soul is probably the biggest act that came out of it. Me And You - they had a couple of big hits. Caron Wheeler and Afrodiziak used to be the backing vocalists down there. Keith Douglas, Pablo Gad and King Sounds and other people used to use it as well. Everyone around here, Ruff Cutt, Courtney Pine, a whole range of people.

Tell me about how you started the UK arm of FORM and your Reggae Focus project.

The Federation of Reggae Music was set up 16 years ago. The Arts Council helped set it up and gave us some money. One of the successful things we did was called Music Means Business with the PRS and the Musicians' Union, BCAP and various mainstream organisations. We're going to be starting them again this year. I think people need to be educated and trained in the number of areas. Right now we've got four young people in university doing media studies degrees. Taking them from high school or academy into college or university.

I've been talking a lot about Reggae Focus 2012. The whole project is actually called Sounds of Jamaica. It's a three-year project we're doing, looking at turning UK reggae up on its head if we can. I'm an elder statesman but I'm trying to think in a modern type way. There are a number of things that are not happening with reggae at the moment. And most of the changes that tend to happen come from Jamaica and they're not always very positive.

But in terms of development of the music, some things you don't need to change because people like reggae the way it is to a certain extent. But we also have to keep abreast of the times. Where dancehall is going there is a lot of potential for certain things to happen but from a Jamaican angle I think it's a bit local. Particularly the type of lyrical material they are dealing with. It's very local to be talking about the Gaza and the Gully business. And because young people are looking to Jamaica for inspiration the negative things may spill over into these countries.

The PRS are going to be helping us. We need to put more emphasis on stuff that we do over here. I've talked to about six or seven Jamaican producers and we're going to be working with some of them who share the vision that we have for reggae as a whole. But one of the things we're looking at is we need to make it more fun. You can have conscious dancehall. We're not trying to say people must do conscious stuff but as I said so many times “How many times are you going to tell someone how good you look or how fresh you are?” It's all good but the rest of the world are dancing to another beat in a sense.

Some people don't like Lady Gaga, Rihanna or Nicki Minaj. But I find it all interesting. I understand it's people just playing the system and getting away with it! If you're making some money, not going over the top with certain things and having some fun then it's all good for me. I don't think there's anything wrong with dancehall going in that kind of direction. Nobody's getting killed as a result of it. We want to see dancehall enter into the pop arena. There's a lot of potential for it to happen with nice sexy girls and guys - let's get them on some proper rhythms. We're going to be having talks with the BBC about daytime and night-time radio play for reggae music. The Voice took it up the other day. And we're going to be building on that stuff.

But at the same time the onus is on us to do things. Because you can't take certain things to the BBC and expect them to play it. You might say that they're racist or whatever but I'm saying “if you've got something that's good and you're going in the right way about plugging it it will happen”. Because my music was not commercial when I was signed to Virgin but I was getting through with things because maybe I wasn't getting stupid? Some people say I was a bit militant but I don't think I was as militant as some people! But we're in a different time at the moment and I'm saying that people love reggae everywhere that I've been to. It just needs to step up a couple of places and join the rest of the world.

So how did FORM give birth to Reggae Focus?

Well we started Reggae Focus 16 years ago. That was the first thing that we did. But it was slightly different. It was like a touring concept where we had seminars with the musicians' union and PRS. They’ve got different chapters all over the country so we could work with them to inform reggae musicians about their rights, publishing and intellectual property. What they need to do if they need to gain access to stuff like funding. We've raised hundreds of thousands of pounds for people who do tours. Macka B was the first artist we actually worked with. People like Winston Francis have benefited from it. We started touring with Earl 16, Aisha, Twinkle Brothers, a range of people benefited from touring opportunities.

We are having a more multicultural approach to what we are doing. We always have done, it's just that we're advertising it a bit more. Because I grew up in this country where lots of young white or Asian people loved reggae. People like David Rodigan are a case in point. Because some people think Rodigan came in as a wagonist. He didn't. He was there all the time with us when we were growing up.

When I started Federation Of Reggae Music I called David Rodigan and he said “You know I'm involved in anything you're doing. Just count me in”. I'm happy with David. He's got an MBE and some people have a problem with it. More power to his elbow. David Rodigan is an ambassador for reggae music. He's researched, he knows about the thing, he can lecture and talk about it. There are certain of our people who are going to have a problem with David Rodigan because he is making money out of this. If you've gone to school and you done your work and you've graduated, you get a job! (laughs) That's how I see David Rodigan. And people like Nick Manasseh and all those other people who are doing really great work.

It's like John Masouri. John Masouri is a big part of what I'm doing, in terms of my connectedness with John over the last 40 years. Those people were there right from the beginning. He was one of the first people to do an interview with me back in the day. We've always kind of kept in touch regardless of what was going on.

What I'm doing is organising and bringing people in who fit in. It's like a Twelve Tribes thing. What you're doing today is part of the programme for me. We can't do it without people.

My thing is reggae music has always been a multicultural thing in Jamaica. The first man to have a studio in Jamaica wasn't a black man, it was a Syrian. I want to get away from the colour thing. And deal with the human thing within the business. My shop is open to everyone as long as they want to be positive. Any young person that wants to do reggae or dancehall, we can help them to do it. If they're going to set up a record label, we're going to help to set it up. If they want to become a promoter, we're going to show them how. The wider the thing gets, the better it is for everyone. You can't tell Japanese people “You can't do reggae”. The Chinese thing is really developing in China. And right around that belt in Indonesia. Reggae is really happening in those places. So we have to reach out to those people.

You mentioned on the phone that Gappy Ranks came out of one of your programmes. Tell me what you've been doing recently for music in this borough...

HPCC Bridge Park was Britain and Europe's biggest community initiative. It's a massive centre to help young people dealing with businesses. People have sporting interests. It’s there for anything that young people in the community aspire to. It's there as a platform to help them to get a start in life. So we developed the Talent Corporation International as part of Bridge Park.

A brother called Mickey D was like the Mr Fix-It reggae man. He lived in England but also worked in Jamaica. He and I and Lawrence Fearon, Delaney Brown and another brother called Arnold Curlew. A very good brethren. He was somebody who was all about business and getting money from the public sector. Flip Fraser had Black Heroes which was part of TCI. And eventually I got people like Paul Weller, Anna Joy David from Red Wedge involved in it as well. Anybody who was anybody at one time. Total Contrast - which was Delroy Murray. Stevie from the Adventures of Stevie V. All of those guys are part of this organisation.

Geoff Thompson, former five-time British and world karate champion, came and brought the sports context into TCI. Geoff has since gone on to set up the Youth Charter for sport, based on the same TCI ethos. And the Youth Charter for Sport is now based in about 36 countries all over the world. People like the BMIA. They were all linked to it. Byron Ley Fook and Root Jackson. Black Theatre Co-operative, Judith Jacobs, Phil Fearon, all of these people.

These are the things I've done just on the reggae side. People like David Grant who I used to advise and help them in management to help them get started. Hi-Tension and these people you've heard about. It was me that told Chris Blackwell that “These guys have done this thing and nobody is listening to them.” I got Chris Blackwell to listen to Hi-Tension and put out a record that was a big hit. There are so many people we have helped right across the country. Not just in London. If you look at Steel Pulse, it was me that helped get them signed to Island Records.

We set up the Federation Of Reggae Music as a trade and development association for reggae music. That was with the help of the Arts Council London Boroughs Grants Unit - Brent council, Barnet, Harrow, Ealing council. It's to help get more recognition for talented people. Not just reggae people but talented young people all over the place.

And then there was AIM, the Adventures In Music thing that we set up. AIM was specifically to help young people to make a difference in their lives through music. Now we weren't about to say “all of you have got to do reggae music”. The Arts Council put up a substantial amount of money for us to do some research and development work into the artistic and creative needs - particularly of African and Caribbean young people.

Lo and behold, I started going up and down the country and it was sad. It was tear-jerking. There are just so many talented young people in this country doing music. I'm talking about black kids, white kids, Indian kids, Chinese kids, we've come across all sorts. You go up to Liverpool and it's frightening. Britain in my estimation could be the talent farm for the rest of Europe or for the rest of the world. Because there's just so much talent and it's like a whole mine that is untapped. What you're seeing on X Factor and The Voice, that's not even the tip of the iceberg.

And there is very little support being given to these young people. There's nothing happening for them. In this country where they were born. There was no hope. There was a part of our project called Hopescope which was about providing young people, whoever they are, with some hope.

How do we do that? I teach. I'm a martial arts master. I don't look it now (laughs) but I teach a thing called Kateda. Kateda is all about the mental side of things. It's all about mind control - not in the sense of wanting to control people but showing people how to to control their actions and emotions through that particular kind of training. It's not a fighting form of martial arts. You can use it for self-defence but our argument is very simply this: “If you think peacefully it is highly unlikely that people are going to attack you”.

But your mind is always under attack. Wherever you sit down there something that's bugging you. Our thing is meditation. We're talking about using Dharma in Buddhism or its equivalent which is good moral livity. Backed up with meditation, it is key to survival. People say “Delroy, how does that fit in with your Rastafari?” and I say “It fits in perfectly”. Because from our perspective most religions are saying pretty much the same thing. It's just that there are a lot of people who politicise religion for their own particular ends.

If you travel all over the earth what do most people want to be? They want to be happy. Music is a force that makes people happy. I know reggae music is good that way. People don't have to learn any specific kind of dance or dance in some regimented way. People might say “You can't dance” but you can move any way to reggae freely. People just have a laugh at how you’re dancing and feel good about it.

Britain has a kind of positivity about it - if it is tapped into. My cousins come over from New York and say “It's funny how black people and white people live in the same area and they're not fighting. You'll see black people coming into your sister's house and white people coming in and some Indian people coming in and it's funny how that works over here. There's nothing like that in the States”. So for me that is positive.

I talk a lot about this British way. The way the people can be slagging each other off around the table and then meet up later and be fine. Some people call it fake. I call it diplomacy. It's like the way that Labour and the Conservatives can see each other in Parliament but when there's a war we all pull together. That's why I tell people there's a lot we can learn from this British way. We don't always have to be fighting each other because we don't agree with each other. We bring the British attitude to the table and we will promote the British attitude when we go abroad. I went to Jamaica and I spoke English on the radio. It sounded fascinating. A Rastaman is speaking English on the radio. And people absolutely loved it. It was on Dermot Hussey’s programme when I first went back. Sometimes white people phone up here and I say “Hello” and they say “Hello we're after Delroy Washington?” Because they think I should say “Wh’appen”! (laughs)

And I would like us to build on that success. The potential is here in England for this to happen. To convince the politicians or the policy makers it doesn't have to be doom and gloom. It doesn't have to be a charity for everybody. Because if people are not greedy there is enough for everybody to survive on the planet. The earth makes enough to feed everybody and more. It's just that some people want more than their fair share.

I'm positive that if young people knew there were some farms out in the country that wanted to hire them, a lot of people would be quite prepared to go out and deal with some agriculture. But because people are moving more towards the manufacturing type situation, everybody's forgetting about nature or what we need to grow to eat. I love computers but there are other things happening. Young people need to get out of London. We've done that with young people when we've been going on tour. People like the Status Crew and those people, a lot of these kids have been on tour with us.

We want to take more young people out of places like Stonebridge or Hackney and take them out into the country. We've done that with some of our people with martial arts. Taking them out of there for maybe seven days and they love it out there. Some of them don't even want to come back. People are in tears when they've got to come back. Because of the concrete jungle type situation.

So yes, music is good but we've got to teach people what it is to live. Because society is educating people for work when we should be educating people for life. When we start educating people for life things like racism go out of the window. This is not religion. It is a spiritual form of life. The meditation that we teach is not linked to a religion. Some people might say “All this looks Buddhist” but you could be Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist whatever - you can come and learn this thing, go back to your thing and find that your life has become improved as a result.

Some people might say “You're trying to create a new religion” but we're not trying to create anything because everything is already here. “There is nothing new under the sun” as the good King Solomon would say. Basically what we want to do with our music is share an alternative type lifestyle for people. We have to bring people back to the essence of their lives. What is the essence of your life?

I don't know but it sounds like John Paul Sartre - he talked about essence!

(laughs) Yeah, John Paul Sartre. That's who we were talking about earlier on! The essence of all of our lives is breath. No breath, no life. We can talk about God but God means different things to different people. We don't have to go into any kind of subjective religion to talk about breath. So our thing is to bring people back to the essence or the rhythm of their own breathing.

When we learn what it means to breathe, life is simple. It is as simple as breathing. It's not a man telling you about some big philosophy about religion. But we do say you have to practise your breathing thing regularly or you'll find it doesn't work for you. Because the first thing I did this morning when I got up was breathe. And I know I feel good right now just doing this. The martial arts side of what we are doing is great because you find out your own potential as a human being. What you're capable of in terms of what your body can take more withstand or what it can't withstand. But it's all done through breath. That's what I've learnt.

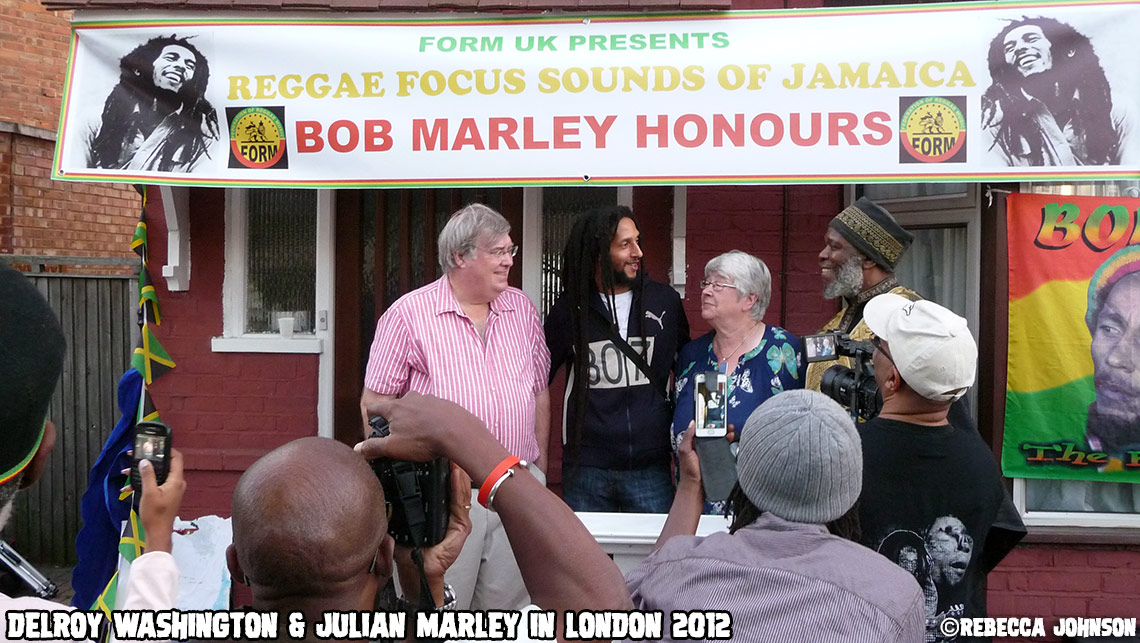

You've also been busy in 2012 putting blue plaques up in the places where Dennis Brown and Bob Marley lived...

The Bob Marley Honours project is part of the Reggae Focus: Sounds of Jamaica initiative. It's a 3-year initiative. The objective we would like to see at the end of 3 years is better facilities for creating music, better venues, particularly in Brent. Brent is meant to be the reggae capital of the UK. The Heritage Inn up the road is a start. We have Bridge Park around the corner here.

But to get back to the Bob Marley Honours, it’s part of a centerpiece of the Sounds of Jamaica. Bob Marley is the focus of what we are doing for major reasons. Bob Marley through his work and his action has proven that reggae can get to the top of the musical hierarchy. Right now Bob Marley must be the most famous musician on the planet. Yes people still talk about Elvis Presley and Michael Jackson but you don't see as much of Elvis Presley or Michael Jackson as you see of Bob Marley right now. So I'm saying the more we big up Bob Marley the more reggae will get big. Bob Marley lived in Brent. The whole of his mission that he had, began to be fulfilled here in Brent.

I get sad sometimes [about Bob] although after a while I feel happy. Because I was a witness to one of the most phenomenal mad things that has ever happened on this planet. I'm not talking about all the hype behind it. Sometimes I say I knew two Bob Marleys. I knew a Bob Marley who had some serious ideals, who could dream about wanting to see the most fantastic things happen for people.

And yet people got in the way of Bob Marley fulfilling a lot of what he wanted to do. Because people are often very fickle. Even his own brethren got in the way. If I'm going to talk the truth about it. I think people like Bunny will admit that when certain things started they didn't really understand where they wanted to take this. Bob was focused on what he wanted to achieve and that's why he achieved it. Bob stuck with one record company and worked with them until he got to the top of his game.

I was there with him from day one. I was like his little disciple. The little acolyte who followed the high priest around (laughs) and saw what was achieved because a man had faith. Everyone can talk about Rastafari this, Rastafari that. I knew Bob Marley and I know something about Rastafari. I'm saying that at the end of the day Bob Marley has given millions, untold millions of people all over the world, hope. Which is what we want to take from the work of Bob Marley and this is why Bob Marley Honours is important. We want to build on the work of Bob Marley.

Bob Marley's children are doing that. Cedella is doing it, Rohan is doing it with the Marley brand coffee. There's a lot of charitable good work. It isn't about them just putting the money in their pockets. I've been on this work here from a longer time and this is not something to put money in my pocket. A lot of people earn money or fame through some of the stuff we've been doing and that's good. But I'm saying famous is not enough. If you've got fame you've got to use that to enhance something. Like what Ziggy and Cedella and Rohan and the rest of them are doing. They're trying to change people's lives through the work of their father. I'm saying that hopefully, Jah willing, we’ll be working together with them.

What's the programme of activities?

The programme of activities begins with the blue plaque. We're going to be creating a map of blue plaques right across Brent. We're going to honour some of the people like Bob with the blue plaques. That's the first part of the project.

There's a little roundabout just down the road and we're looking at calling it the Trojan Roundabout. Because it's just in front of where Trojan Records used to be. We're looking at having the Trojan logo down there. And across the road where the courthouse is we’ll have a plaque saying this is where Trojan Records was here. Desmond Dekker lived in Cricklewood. Gregory Isaacs used to be down the road. It's all very exciting.

And Jimmy Cliff was over here for a while.

Jimmy Cliff lived here for a long time. Lived in Cricklewood and Willesden. Ken Boothe lived in the area, Alton Ellis lived in the area. Slim Smith lived in Kilburn. Dave and Ansell Collins and that whole gang live here. Dandy Livingstone lived in Kingsbury.

Down in Neasden we want to be putting up a big statue of Bob Marley and the Wailers. Because they're the most famous people who ever lived in the borough. People would come to Brent just to see those things from a tourism perspective. And it's something that ordinary people could feel good about. This was a man who is not a black man or a white man, he was human. I've said something like that and some people took it like he doesn't want to be black because he's famous. But it's politics that's made you and me black and white. The creator never made us black or white. Because you look kind of pink to me. (laughs) You're a different colour from Frank for a start laughs. We want to get away from the eugenics nonsense.

I'm saying we come from a community. Bob Marley would say he is neither black nor white, he was a human being. So our thing is really about showing people “All of us are human, we can all live together here”. So this whole programme has got that philosophy behind it.

Brent was where we created the One Love festival but that's gone. I created the One Love festival here to help roots music and people who want to create roots music. Some people had other ideas. When we did the first One Love thing we had Abyssinians on it, we had Twinkle Brothers, we had Royal Rasses, all for 8 quid. Tickets were selling faster than records in record shops.That was 1989. All the newspapers wrote good things about it because there was no fighting, no trouble. It wasn't about people hyping themselves up or pushing up their chest. It was a peace concert. Billy Ocean came and Billy enjoyed it. He wanted to do his song, it was such a good vibe. That is my vision for reggae. Like we say in the Bible, it's all Nations.

The blue plaque is about recognising a Bob Marley international reggae festival. It's not charging people big silly money to come into a concert. What does it cost to get into a festival these days?

Depends on the festival but in the UK could be £200 for a weekend.

Well charge 25 quid. and we can fill out Wembley arena probably five nights a week. No joke it can happen. We want to work with anyone who wants to help us create a better future. Creating a better present now. It's about bringing the community together. People whose potential is not being seen, giving them an opportunity to shine.

Let’s talk about the Marley film - many people questioned why you were not involved as a contributor…

I wanted to be involved actually. I would have gladly taken part in it had Kevin MacDonald's people not offered me what amounts to less than peanuts. They told me that they only had 150 pounds to offer me and you can quote me on that. They would have been better off asking me to do it for free - rather than insulting my integrity.

I did start telling them about certain things that certain people don't really know about, like the whole period with Johnny Nash. Because I was with Bob when Bob started from day one. I was at Ridgmount Gardens. I was at Cromarty Villas, Neasden, I was in all the places at Chelsea. Even when I had my deal with Virgin I was still there. I went and lived in Jamaica and I was the one that took care of the house while Bob was over here. I was the one that was rehearsing the Melody Makers with Rita up in Bull Bay. So there's all kinds of stuff that I know about the Wailers.

I don't want to do any kiss-and-tell sensationalist stuff but there are some other interesting things that people haven't heard about Bob Marley and the Wailers that I think people would be interested to know. For them to understand that he was a very human being. With a light side and dark side. And people have to understand why Bob was this way inclined.

I'm saying that Bob because he was mixed race - I don't even like using that term - but because he was a product of black and white, he had certain issues. Because one of the things that Bob wanted was he wanted to be more black. Then there were some issues with certain people saying if Bob wasn't mixed race he wouldn't have got to where he got to. I'm saying that's a load of bollocks. Bob Marley was genuine, he was a real talent. Maybe him being a certain way might have helped. Bob Marley was very good looking. Bob Marley was very marketable from a music business perspective. CBS records didn't know how to do it. Chris Blackwell did. Chris Blackwell knew how it could work and I'm saying to his credit he did it. Island Records almost got broke trying to promote Bob Marley. Chris Blackwell was the person that gave me my first big break. People might want to say what they want to say about Chris Blackwell. All I know is what he did for me. And I know what he's done for a lot of other people.

What did you think of the film?

From my perspective the film is ok to a point. Obviously you can't do everything in two to three hours but a lot of things are missing. The fact that I am missing in it, there is something wrong with it. There could be so much more to it which is why maybe there is scope for another Bob Marley film. There's a kind of soul that is missing from it. What Bob Marley aspired to as Rastafari. A lot of people say he was just a glorified hippie but there’s more to what Bob believed than what some people care to understand. Why did Bob Marley see Haile Selassie as God? How did that come across in the film?

They just focused on him as a man.

What made Bob Marley the man that he was, was what he believed. They start the film in Africa which is ok but why don’t you start in the hills of St. Ann or Westmoreland with some binghi man playing the drums? Start talking about Rastafari first and show some of those dread looking people in the bush. You start by showing Jamaica as Rasta country. When I was living in Jamaica what was really striking was every time I would wake up before the sun would rise, without fail I’d hear one drum going boom. You hear my record Chant One? This is it. You hear the crickets.

Like stick percussion.

Yeah! My Chant One is about that. You hear a cock crow. Then you hear one or two cars. And when you go over to Bobo Hill you hear pure drums. Like hundreds of horses coming through the mountains. The natural echo. I know why slave owners used to be really scared of the drums. It sounds like a mass army of people. If you capture something like that in the film then Bob Marley comes into the heart of all that.

You have to tell the story of Rastafari to really sell Bob Marley and where he's coming from to the world. There’s a whole pocomania thing going on as well. The poco thing and the Bobo thing have some kind of convergence.

It’s not just people talking. There’s a whole lifestyle going on. Where are the sound systems? I remember in 1976 when he did Smile Jamaica and it was like magic in Jamaica. There were two versions - the slow version and the fast version. People stopped in the middle of the street when they hear it, you know? Old women with things on their heads dancing. It’s magic. Smile Jamaica was everywhere. They failed to capture that.

The whole of Jamaica could speak about Bob Marley. All you’ve got to do is go to where the things are happening. Studio 1. Bob Marley came out of a live environment. I found it a bit static. It’s not live enough. It doesn’t capture the essence of what Bob Marley was about. And what Bob Marley was trying to convey. The interviews are ok but it’s not all about people being interviewed.

Show it, don't tell it.

Show it! You understand. You should do it. (laughs)

Final question, what’s the name of your book and when’s it coming out?

Ahhhh…. I’ve got a couple of books. Reggae A Living History - that is the first book. That’s going to be part of the Reggae Focus: Sounds of Jamaica project. We have a documentary that we’re doing: Reggae from JA to the UK. It’s the book, in film version. It’s looking at things that other people tend not to see when they’re writing or they’re making documentaries. Reggae is a very organic music.

I think sometimes in trying to sensationalise things they miss the point. Real life is far more exciting than a movie. Why was it that those kids in movies in America like Boyz n The Hood didn't take millions of pounds to do yet they made millions? Because they were dealing with real subject matter. Those were reality movies. So my book and my documentary are the same thing. The documentary is just the visualisation of the book. It's going to be difficult but I know all the people.

So what's the other book?

Well the Bob Marley book is the other thing. Because people are always telling me to write a book because I've got a lot to say. We're doing a synopsis of that within the Reggae Focus: Sounds Of Jamaica. We want to bring out a booklet that will tell certain things in pictures but we need to link up with all these people to get the rights to use some of the photographs.

But what about the story of Delroy Washington? Shouldn't that be a book?

Somebody said to me “Why don't you do a book of yourself and then put Bob Marley in it?” I could do a book of myself and I could put Bob Marley, Dennis Brown, Ken Boothe, Alton Ellis and all those people. Because the Delroy Washington book is about all of those people. It's like the whole story of the Twelve Tribes of Israel that I have got to tell. It’s part of the whole Delroy Washington story.

Because there are some people I know that are really interesting. Lloyd Coxsone is a very interesting person. Apart from the work he's done with sound systems in this country, in Jamaica he has done some mad things. I remember when I first went to Jamaica Lloyd set up an engineering company where they fixed cars. He was providing jobs for loads of people around his area in Harbour View. They also did things like bridges, civil engineering type stuff. One bridge that nobody in Jamaica could fix, a bridge that was falling over, his people went in and fixed it. It was big headline news in Jamaica. So he's doing a whole load of stuff providing stuff for kids in Jamaica and people don't hear about it.

God willing some of this stuff might come out but I need to be somewhere where Bob is buried up in St Ann. I need to be away from all of this to be able to put all of it into perspective. Because sometimes when I'm here it's too busy. I need to be somewhere far away - maybe out in the bushes somewhere in England. Or Jamaica or Africa would be ideal. Because a lot of the stuff I'm talking about needs to be done.

PREVIOUS INTERVIEW PARTS HERE: PART I, PART II, PART III

PHOTO CREDITS: Felix Foueillis - United Reggae & Rebecca Johnson (London 2012)