Delroy Washington ADD

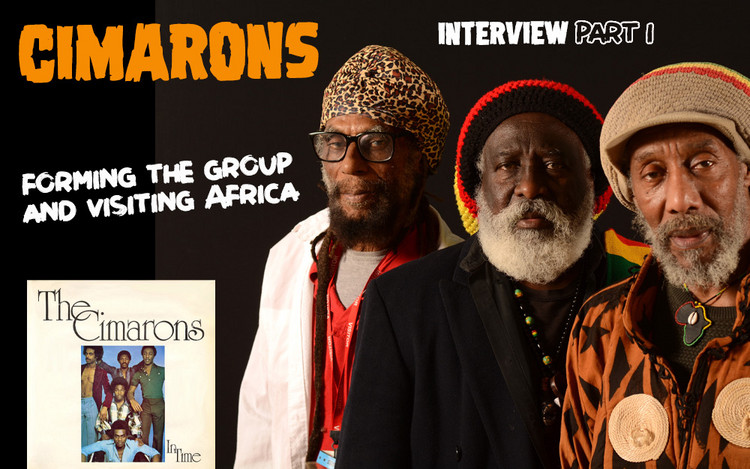

Delroy Washington Interview (2012) Part III - The Virgin Years

05/16/2020 by Angus Taylor

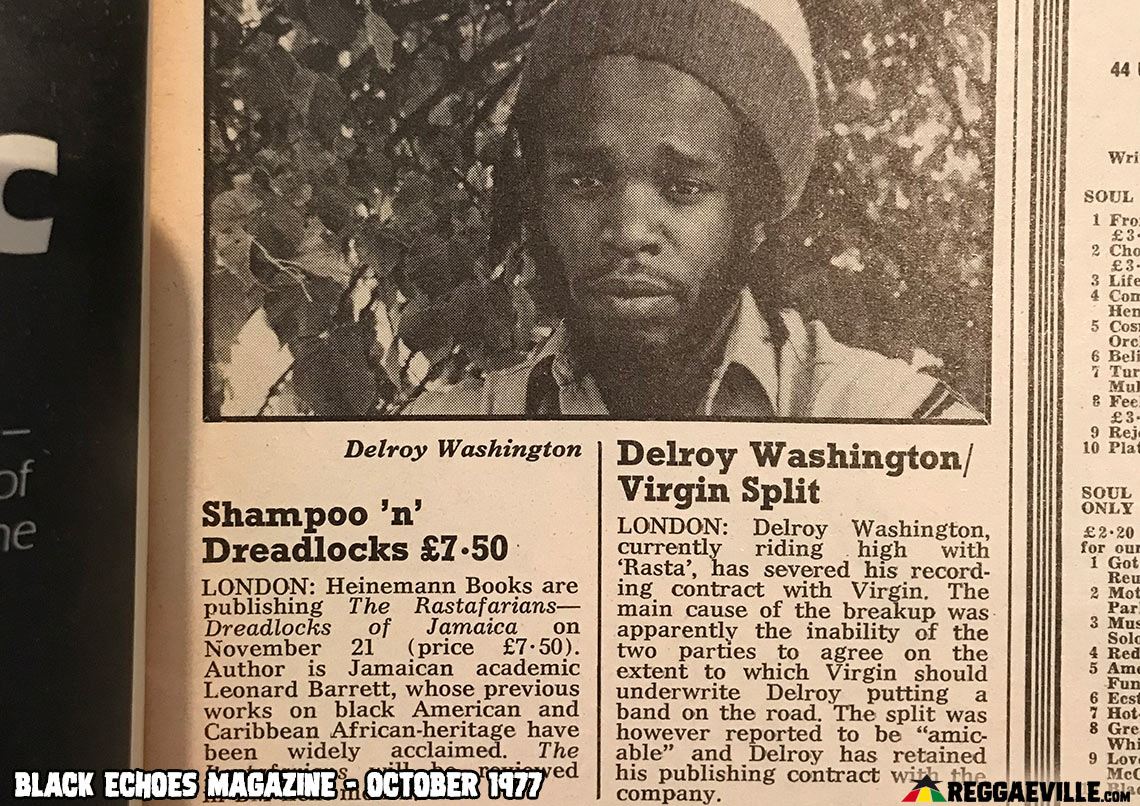

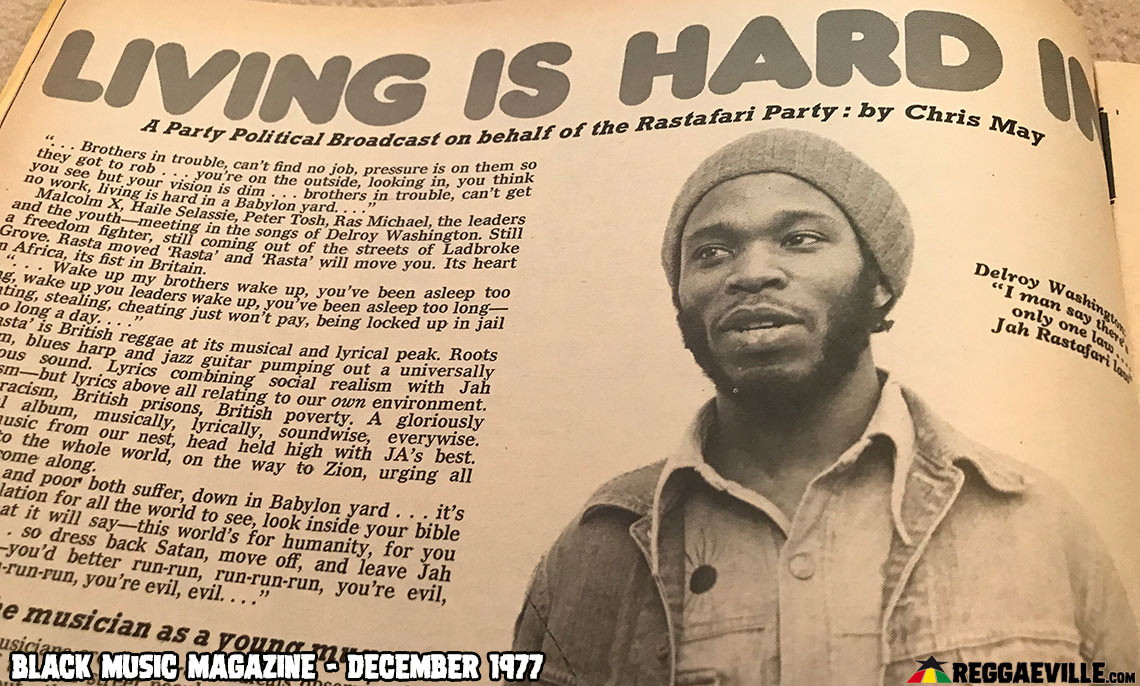

In the third chapter of our 4 part interview with Delroy Washington, he talks about his two albums made for Virgin Records. He also shares his philosophy of music, his memories of punk rock, and a poignant eulogy for his father...

It sounds like you were signed to Virgin while all the stuff with Bob and Aswad was happening...

Oh that was before.

Funnily enough the Virgin Encyclopaedia Of Reggae says you signed to Virgin in 1977!

Rubbish! (laughs) I was in the process of getting signed to Virgin from 1975 but I was signed to Island before that. In fact I had my own label before going to Island. Chris Blackwell heard my stuff, he wanted to know where I did the music because he thought I did it in Jamaica! I said “No, I did it in a little studio called Gooseberry studio up in the West End.” And he couldn't believe it. So he said he was going to give me a deal. “Start off with two records. We want two singles and then we'll look at doing the album after that”. It was like I'd won the pools (laughs) because I’d always been at Island but... [not recorded for himself].

Chris Blackwell gave me the studio time. I was on a retainer which was good because it kind of took some pressure off me. I started doing the rehearsals to do the two tunes but things were so easy that I ended up doing the album. Although I had problems with it. It didn't come out the way I wanted it to because I had problems with musicians. I could have played stuff myself but I got my brethren because it was a way to get them some money. You rehearse, you play on the session, you get money. So I brought in George and the rest of the men, some of them that were now going to form Aswad.

And Pat Thrall. A rock god you know? He is a rock music legend that played the solo on Freedom Fighters. Because those were the songs I was working on. He is a god for Slash and people like that. He's one of the most terrible guitarists on the planet. The first solo that played on Freedom Fighters - if people had heard that! But the guy I was working with in the studio didn't take it. I said “Right that's it! We don't want to play anymore” and my man said he didn't take it! His name was Guy Bidmead. I think that was who was doing the session. I was really upset because he didn't take it. I said “That was the solo that we wanted!” He did it right the first time. Anyway he went over and redid it.

My whole thing is I've got some music which I don't think people understand. I don't think some people understand where my head is at musically. I think if they had done we would have got on another level from way back in the day.

Anyway the first album, I was at Island, I had all the stuff finished and it was almost like I was stuck. It wasn't going anywhere. It wasn't going out. Chris was in Jamaica and I was kind of an independent person. So I was waiting around and waiting around and I heard about this company called Virgin. I really didn't want to leave Island because Island was like home. Because I'd been there with The Wailers, so being signed to Island myself was like “I'm on the same company as Bob now”.

But I heard of Virgin, and Mikey Campbell was always around encouraging me so I talked to Mikey, and showed him what I wanted to do. He took my tapes to Virgin and the same day Richard Branson said “Here's 2000 quid” and told me not to go anywhere. Gave me two grand! Send it back with Mikey. Mikey was over the moon. He had never seen two grand before. We're talking about black people in the 70s here. Everybody was broke in Ladbroke Grove! (laughs) If you weren't selling weed you had no dosh. Two grand, same day “Go and buy yourself some clothes, get yourself some things, go and do a bit of shopping”. I took a grand and gave Mikey the other one and said to go and set something up with his wife. Mikey just wanted to keep holding the two grand! (laughs)

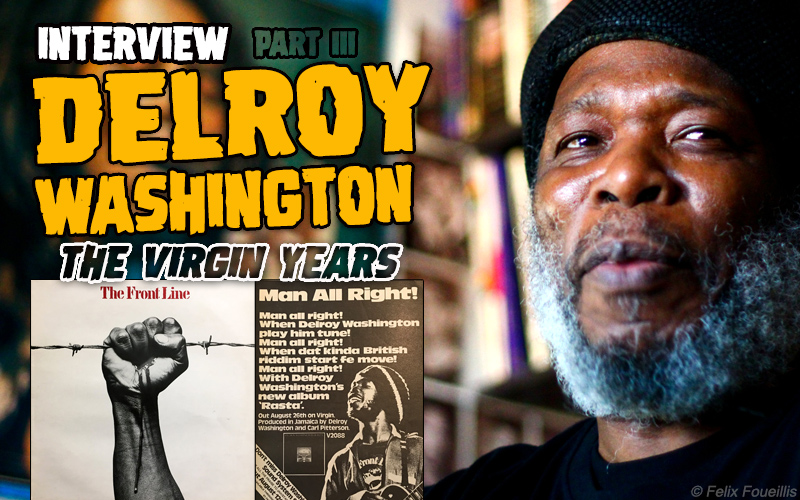

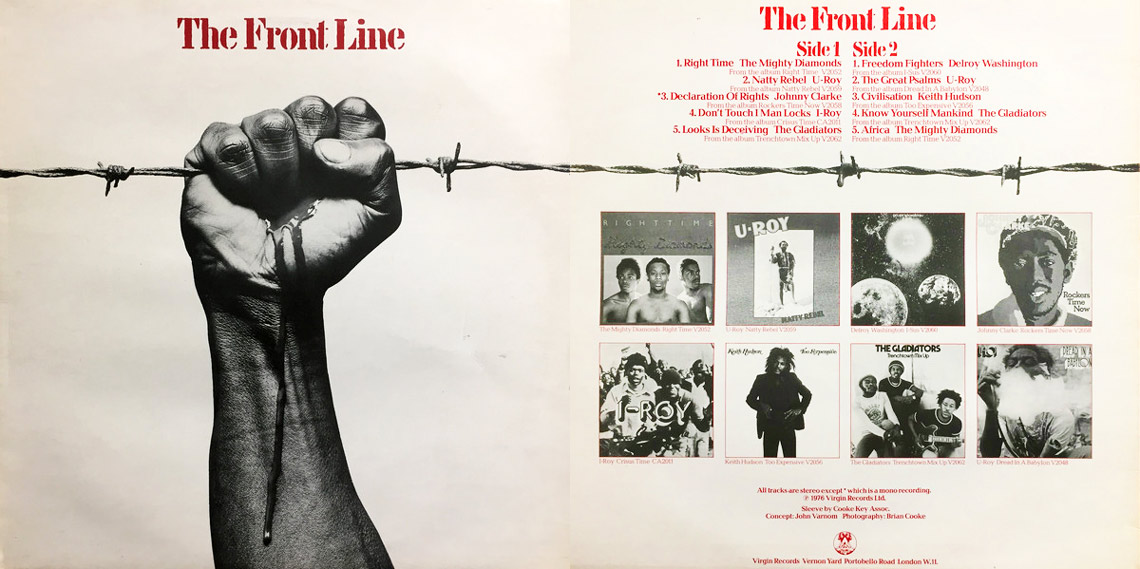

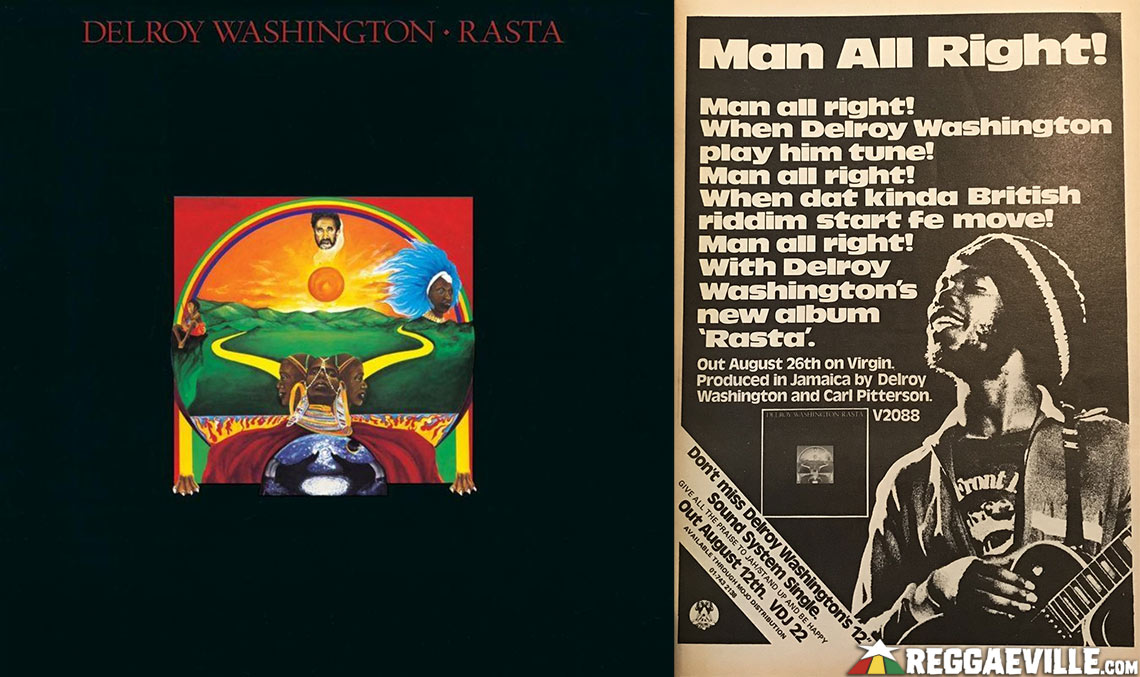

So I went back to Virgin who said “You're going to be the next biggest thing since Bob Marley. In fact we're going to make you bigger than Bob Marley.” They weren't joking, they were serious. I signed to them and I got 30 grand which was serious money - like 3 million quid to me in those times. I got 30 grand to do the album and then more money was to follow so I thought “Let me just follow the money!” And Virgin were true to their word. They said to us they were going to put this compilation album together. Remember the Tighten Up thing? They were going to do something similar to Tighten Up.

This was their 1976 Frontline compilation?

Yeah. They said they were going to put it at number one in the charts. And I thought “Number one, if you say so”. But they did. They brought it out and did major promotion on it. It was sold for 99p and the first week it came out it went to number one, top of the charts. And then we were going to start planning the Frontline Rockers tour.

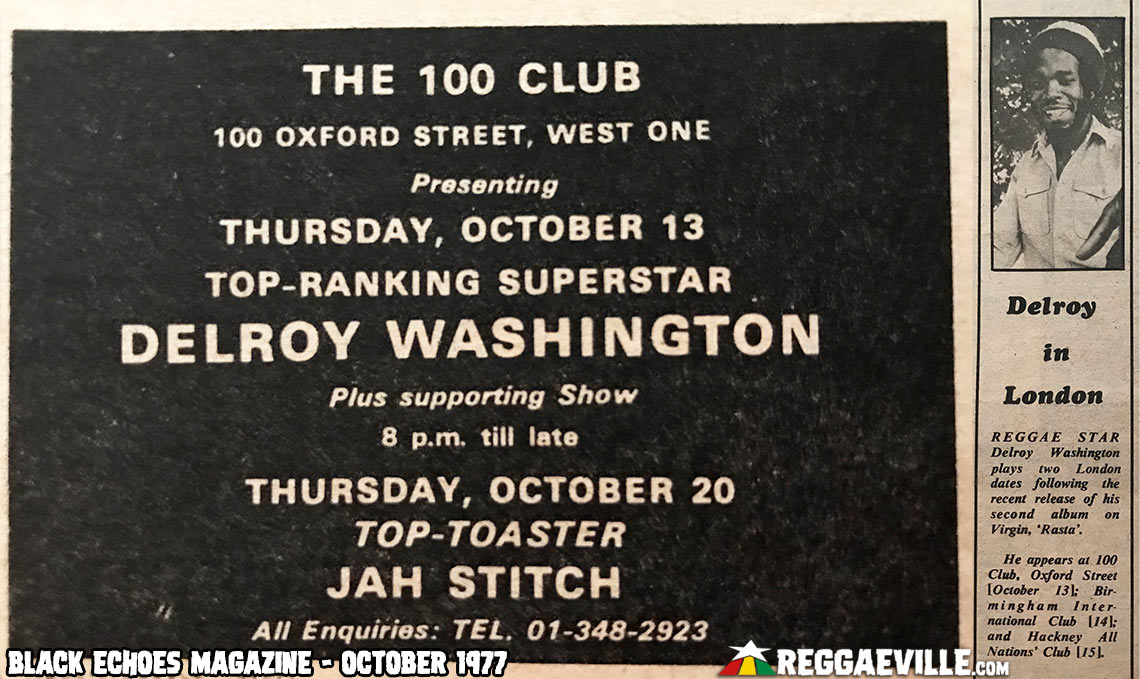

But we just came up against bad luck because we started at the Lyceum. I don't know if you've heard of the infamous Lyceum gig? The Lyceum gig was with myself, U Roy and the Mighty Diamonds. The three of us at the Lyceum. Trust me, pandemonium in the West End. It was just the whole West End. I went outside and almost couldn't come back into the venue. Police were saying “Why didn't they get a bigger venue? This venue is not big enough for this thing.”

So the police had to be out on the street. All kinds of nonsense going on out there. I think I've still got one of the papers and I still got the headlines. It was a very infamous gig. For the fact that a lot of white people came to the gig and some of the kids were mugging people and all that stuff was going on. Because black people were saying they can't get in and why should some white people get in, some racist stuff happened on the night. It was very nasty.

But it was a great gig. I think that gig made me in a way. The records went to America because then CBS Columbia signed me as well. They signed me over there through Virgin. Things were really happening. I was like moving around with The Wailers. I couldn't shake it all off! I was still doing stuff with Bob at the time.

But then I was still in the community thing with the kids. They were not having anywhere to live and there were a lot of houses empty. We found out about the squatting rule. Me and my brethren Sam Jones, we gave them houses because black people couldn't get any housing.

I've never been that far away from the community. Everybody knows that with me really. So more than just being an artist my claim to fame is that I'm the artist that's always been on the ground. I can be here today or I can go to a place in Brixton or I can go up to Twelve Tribes. I was one of the people who set up Twelve Tribes of Israel over here. That's another story. Twelve Tribes may have been the difference between a Rasta artist making it in this country. Because people were saying “Island did this, Island did that” - yeah they did. But I'm saying Twelve Tribes made all the difference. Because if you check out the records you'll find that most of the artists that made it came out of Twelve Tribes.

“You must be one of the Twelve, you can't be nothing else” - you know that tune by Little Roy?

(big laugh) Yeah “You must be one of the Twelve, you can't be nothing else!” With the exception of Abyssinians. But all I know is that with Twelve Tribes I've got an audience.

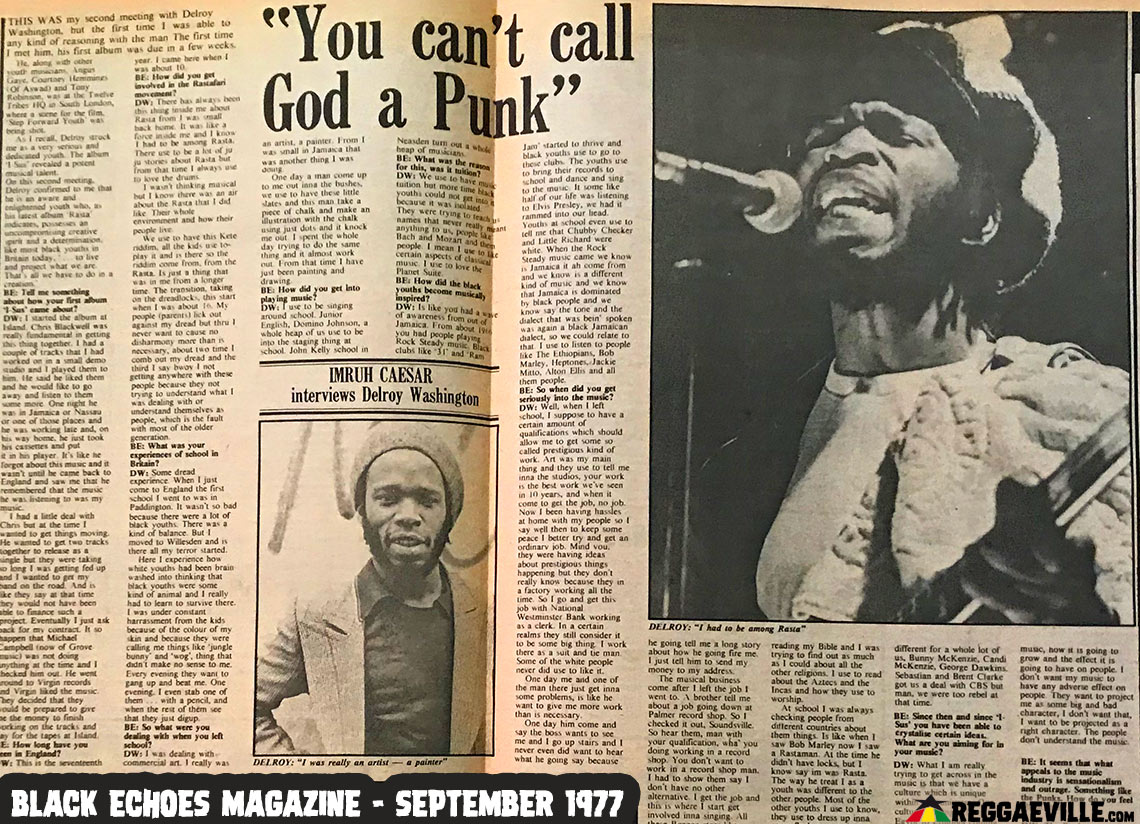

Can I ask you about punk rock and reggae? Because if you go and watch a documentary about reggae today whether it's about Lee Perry, The Four Aces, whatever, there's always a really long section about punk rock and punk and reggae walking together. You were there at the time, what was it actually like?

I think the media tried to play it up a certain type of way. Punk and rasta are different. They were miles apart. But it's like Johnny Rotten and Delroy Washington being miles apart. However, we meet in the middle and we find something in common. That's John and I. I think the punk thing was allowed to happen. It was tolerated in a certain type of way where what Rasta people were doing was not in the same light. While the reggae thing was more popular on the street but today punk is like god.

But no disrespect to it because my thing is: we don't live in a vacuum. A lot of white kids grew up hearing reggae music around them anyway. Because a lot of my white friends grew up on reggae or black music just like I did. Reggae, Motown, Stax, Atlantic stuff. So the music never grew up in a vacuum. Punk was engineered to happen. I think Malcolm McLaren was a very clever guy. People like The Clash. People wanted something to happen.

The night when Sting came to check me was a very nasty night for me. It was one of the turning points in my career. Because I had some very negative people in my band. Because my head was really confused. People are always reaching out. Sting and The Police reached out to me and they wanted us to go and do a tour. I thought it was a good idea but some of my brethren weren’t sure about it. They were saying “What do you want to go on tour with a white boy for?”

To me that night kind of did it for me. I just wanted to leave and get out of the environment. I had to phone up Sting afterwards. At the time we were a bigger act than The Police. I had a deal and they were just coming in. But I'm always up for something if somebody is up for it. Sting and I were supposed to do an album. Then guess what happened after I went to Jamaica and came back? They were the big things happening. So I said “You see? Look at that?”

I got Sting’s number from Vivien Goldman because Vivien was my brethren. She was the media person link in Ladbroke Grove. Vivien was always in my house and if you couldn't find me at my place I'd be down at her house down in Ladbroke Grove. Vivien and I were kind of tight. We’re still tight. Vivien was in tune with everything really. She was the person that knew what was going on. She would tell me “Have you heard of the Slits?” and people like that.

We were all tight in the sense of respect. For me it was just some deprived or poor kids trying a thing. So the punk thing and us wasn't as clear cut as some people want to make it in the media. Because a lot of Rasta resented what punk kids were up to. Rasta was a bit more conservative. The whole thing about spitting at each other at the gig - that wasn't happening. That was not something we were into. If a man came and spat at somebody they were going to be in a fight!

People at reggae shows quite like their personal space.

Yeah, you know what I'm saying? But the musicians like The Clash and what was the group that made the tune called Babylon’s Burning?

Ruts.

I went and bought that record actually. That's one of my favourite records. Bad tune! I also think Never Mind The Bollocks was a good record. It was a good Rock ‘n’ Roll album. If you really want to listen, apart from the fact that Johnny doesn't sing, musically it was a competent album. I don't know why people thought it was rubbish. But I think some people don't listen to stuff. They say “Punk, I don't like it”. But there was a lot of stuff going on in punk that I thought was quite interesting. It was interesting art, if you see what I mean? The whole punk thing was an art thing for me.

I agree, it was an art movement.

That's how I see it. It's a modern form of art. It was very clever stuff. It was like the clothing and stuff. For me it was modern walking living art. That's what I'd call punk. I'd be sitting down at my place and see these girls with their hair in a certain type of way, all colourful. It was all living art. I talk about reggae as living history and I should also talk about punk as living art.

We've talked about your views on a lot of interesting things but we haven't looked at your music in sufficient detail yet. You're one of reggae's great songwriters and there is a complexity to your writing and instrumentation. For instance, Al Anderson's psychedelic guitar intro on the title track to your second album Rasta. Tell me about the different influences that have gone into your songwriting...

I'm going to say this. The real Delroy Washington is still yet to be heard. Because some of the stuff I really wanted to do, I couldn't do it because people always wanted to do something else. I can play you a song now and play the movements and would people say “You can't do that as reggae! That's not a reggae tune”. I'm saying “Yes it can be a reggae tune”. Like this song I've got called Observance. The way it was done was not really how I wanted it to be done.

So did you have creative differences with Virgin in the end?

I was saying something to Virgin at one point and I really wish they understood what I was trying to say to them. It would have been better for me if I went to Jamaica and I found people there who could do what I wanted to do. I loved it in Jamaica because people were not limiting themselves a certain way. The easiest thing is the bread and butter thing where we go in there and we jam from G to A minor. Or we jam from E to G minor. Or from A minor to D minor. That simplicity.

But I met people like Geoffrey Chung in Jamaica. Geoffrey said to me one day “Listen to me. I know what you want to do man. You don't work with the right people. You see me? If I do one album with you, it done”. He said for some reason I'm not singing how I can sing. Because he heard me sitting down and singing with my guitar and he said “That way you sing is how you should sing on your record. It's almost like you're struggling with what you want to do because you don't have the people with the knowledge of the reggae to play how you want to play”.

When Geoffrey said that to me I said “Hallelujah”. Because he was absolutely right. When I went to Jamaica and saw the level of musicianship there... Third World they were saying something similar to me. I wanted to be in that environment. So I came back to England saying to Richard and the man “I want to go back to Jamaica”. I was going to take Drummie and Tony with me because they were my little brethren. I came back specifically to get them to go back to Jamaica because I know when I hit Jamaica, everybody wanted to play with me in Jamaica. Everybody wanted me to be producing for them in Jamaica. So I was on top of my game. Me and Freddie McGregor used to be going around doing sessions all over the place. I played bass. I played guitar. Because Freddie is a major musician and a lot of people don't know that. He is one of the baddest musicians in the whole of reggae music.

He played drums on some Studio One rhythms.

Not just a drummer. He plays keyboards, everything. He plays good guitar, good bass. He's an all-round musician. So I was moving with everyone and I was in the right element in Jamaica. So I came to Virgin and I said “I want to go back to Jamaica” but they probably thought I was just going to go there and leave the company! And I was saying “No, no” and I know that if Virgin had listened to what I was trying to tell them - Virgin would probably still be in the reggae business.

But like I said my stuff is still to be heard. My better stuff has never been recorded. Because I was trying it with people over here and to be quite honest there's a lot of ego in music. There's a lot of ego in reggae. Some people need to let go of the ego thing and we will get a better quality of music. That’s what I'm trying to work on at the moment with some of the younger people. The potential that reggae has... I think some people haven't listened to it enough to really take it to where it could go.

One of the great things Chris Blackwell would say to me is “Delroy if you'd stayed with us Island, right now it would be a different business”. To be quite honest, I was happy being ordinary. It's kind of funny. There was one time where I felt I was being isolated. It's almost like money puts you in a situation where you start seeing things in a different way. Because I think you have to be geared up for success. Like George Michael. I saw him going through it at one time. I saw Michael Jackson going through it. I know Whitney Houston went through it. Amy Winehouse - terrible story. I shed tears because she was just about ready to crack the bloody business.

I've listened to everything and I still listen to everything. Sometimes I'm playing people different kinds of stuff. I still want to do an album with Sting. I would like to do an album with Brian Eno. Because I know that every time I work with someone they bring something to the table. People would say “an album with Brian Eno - how is that going to sound?” I would say I have an idea of how it's going to sound. Because I listen to stuff that Brian Eno does.

My whole thing is all about collaboration. It isn't about music. It's about music as art. I think reggae has got to get back to that level where we stop looking at it as a quick money thing. I think what's happening with dancehall is interesting. I've done a dancehall tune because I know the potential that all this music has.

Stevie Wonder has been one of the biggest influences for me. I've listened to Earth Wind And Fire, Carlos Santana, I listen to Miles Davis. No one believed I listened to people like that. Because on Chant One you can hear Miles Davis in the background. You can hear Carlos Santana in things like Rasta, in what Al’s playing. It's not that I'm saying to those musicians that they should play it. It's just come out sounding that way which is really odd. There's a kind of spiritual kind of communication there. An unspoken thing.

I would have become the kind of artist that Richard Branson and Simon Draper wanted me to become if they were listening to me. Because I was saying to them “I do not want to go to America to go and work with Allen Toussaint. Because Allen Toussaint isn't dealing with reggae”. I know that I could have gone to Jamaica and sat down with people like Mikey Cooper, Tyrone Downie. I could have put all of those people together and I wouldn't have to expend the amount of money that I was spending in England to do stuff.

When I played my stuff in Jamaica people were saying that they didn't believe I did it in England. Some people did like Sly Dunbar, but those man were in studio with me every night. Sly, Robbie the whole of them would come down, sit in and listen to what I was playing. People were saying “Did you really do that music there? It sounds like a yardie did that music”. Some people thought I was making it all up.

But like I said, the influences are many and varied. Bob Marley, all of my brethren, Third World, Inner Circle, all of those bands. People like Harold Butler that I met in Jamaica. Beres Hammond who I think still hasn't done what he is capable of doing. There's so much good music everywhere. I'm into house, I'm into hip hop and rap, I'm into R&B straight, into rock - big time.

So I'm saying the first Delroy Washington album is still yet to come, if people really want to hear some art in a reggae thing. I thought Third World almost cracked it. From the perspective that they just kept doing what they were doing. It was a cross between [reggae and] the Pink Floyd conceptual type stuff. There is space for that. People like good musicianship. They do. I'm getting ready to deal with that because I've got some really interesting people I'm going to be working with over the next few months. What I'm working on now with the Federation of Reggae Music and looking at with the Sounds of Jamaica is taking reggae to that next level.

I got a text from my friend Abdel in Serbia who said he wants to ask you this question: what is the meaning behind the lyrics of your song You Know I Want To Be?

Isn't that amazing? Can you believe that! Serbia is an interesting place. That's near where Emil Shallit comes from. I would like to know that person in Serbia.

You Know I Want To Be is a song about my dad. My dad was a really special person. He was a very humble person. My dad was a really tall guy too. Somebody had to look up to in a really big way. My dad is somebody who had a load of potential. I think he should have stayed in Jamaica. He had a little farm. My dad had bought his farm from long time. It's a story about my father. It's a story about how he had certain ambitions. Maybe he didn't talk to a lot of people about stuff but I used to listen to my father talk and I knew some stuff that he wanted to do. He could have done all kinds of things. He came here and got stuck in a sense.

I think I'm very much like my dad in terms of being a very spiritual person. I remember his funeral. It's not like he was a famous person but people came from all over. They came from Jamaica, they came from America. People came from different parts of London and the country. I thought “He's just a simple guy but everybody spoke highly of him”. Even the minister officiating the funeral said - they used to call my dad Eggy - “You know one thing about Eggy? Eggy was sick and I went to the hospital to cheer him up and when I left, it was me that was cheered up!” That was the kind of person he was. He never worried about anything. He could always see beyond where he was.

A very strange thing happened after my father died. One day I felt I had something wrong with my stomach and I visioned that my dad and me were in England but we were staying in a house in Jamaica where we used to live. He came in and he gave me these two things to eat. He just said “Take them and eat them”. I remember when I got up I was on top of the world and I was better.

My uncle has some very funny stories about my father as well. My uncle’s done very well. He won the Pools twice in England - mad business. He's got a really nice place in Swindon. My dad always went to eat dinner around his house every evening. My uncle is not a superstitious person. He's the most cynical person you'll ever hear. He don't believe nothing. When you're dead, you're dead - that's it.

My uncle said that one evening just after my dad died, my dad always had a certain plate he used. My uncle was saying how he saw the plate move! When they didn't put the dinner in it. (laughs) My father's plate moved over to where my auntie was putting the dinner in! Like it was saying “Put the food in here”. My uncle said if anything was going to prove to him that there was life after death it was that one incident. Because he said nobody moved the plate. There was no wind blowing either. But it just moved across like it was saying “What happened to my dinner?”

Read Part IV of this interview where Delroy talks about his community activism from the 1980s onwards and shares his views on the Marley film….

PREVIOUS INTERVIEW PARTS HERE: PART I, PART II

PHOTO CREDITS: Felix Foueillis - United Reggae, Reggaeville Archive (Newspaper clippings)