London International Ska Festival 2014 ADD

04/17 - 04/20 2014

Interview with Dennis Bovell - PART I

04/09/2014 by Angus Taylor

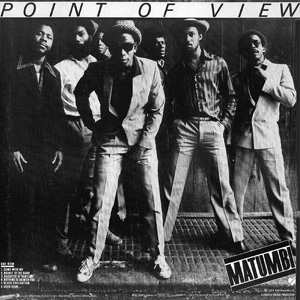

Who is Dennis Bovell? Is he the architect of lovers rock - who helped give the UK its own style of reggae and women more representation in the sound system dance? Is he the Beatles-obsessed songwriter who in the group Matumbi helped bring a broader palette of structures to reggae than just verse-chorus-verse? Is he the dub master whose music sound-tracked the political poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson as he fought racism and Thatcherism? Or is he the globetrotting, genre hopping producer and engineer who has worked with everyone from Fela Kuti to Malcolm McClaren, Boy George to George Clinton?

Dennis Bovell is all these things and more - which is why his importance in reggae and wider popular music cannot be measured. But on April 20th of this year an attempt to celebrate his impact will be undertaken at the London International Ska Festival with an afternoon show at Jazz Cafe titled the Dennis Bovell Songbook. Angus Taylor opened the book on this irrepressible personality and natural storyteller with this two-part interview - that only ended when the recorder ran out of juice. Part one dealing with his musical education and early days in Matumbi is below.

EARLY DAYS

You were born in Barbados in May 1953. What was the first music that you heard in Barbados? Was it religious music?

It was this a cappella quartet of my uncle’s, sometimes it was a quintet. They sang in the church and it was all religious because my grandmother wouldn’t have any other stuff in the house. Even when she had a record player it was albums and albums of American gospel. My uncle bought the Drifters, some Ben E. King, Ray Charles and we had some Sparrow and Lord Kitchener but they were hidden from the old lady because if she ever knew we played them when she wasn’t in the house it would be hell to pay! In fact once before she died I had occasion to say to her “Do you think that it’s possible for someone to be as I am, on stage and playing in clubs and still be a Christian?” and she replied “No” (laughs) - end of conversation!

Before you left for England, did ska have any influence?

Yes, because Jackie Opel who was the lead singer of the Skatalites was from Barbados, so we knew about what he was doing with his Jamaican band. Also my mother had two brothers who were studying in Jamaica. They would come home on holidays and tell tales of what was going on and bring some Jamaican music as well, and hide it from the old lady. “This is the latest and you dance it like that”. But when I came to London I didn’t have to worry about the old lady anymore because my dad was not religious. My mother is but my dad was not at all. He didn’t go to church every week and didn’t see that kind of music as the devil’s tunes. He had a sound system and a huge collection of music and I just used to browse through them all the time. One of the things that I was given to keep me quiet was a record player in my bedroom, so I had a Radiogram that was like a drinks cabinet. Then I learnt how to run a wire to the amplifier sections and plug all my mates’ guitars as an amplifier for when my friends came round and we were learning tunes.

Why did you make a move to the London in the mid-1960s?

Because my parents did. I didn’t want to come but my dad got a job working for London Transport and my mum got the chance to train as a nurse in the NHS. So it was like “You’re coming as well” and at 12 you don’t really have much say, you just go with the flow.

Had you picked up any instrument before you left?

Yeah, yeah, I was playing guitar. My mum’s younger brother, my uncle Sam, played, against my grandparents’ wishes, in a band that played around the hotels. So I was very interested and asked him to teach me the guitar. He started to show me chords, but only religious tunes because the old lady wouldn’t have anything else in the house, so I’d play [sings] Oh, When The Saints Go Marching In and songs from the hymnbook and stuff like that. So when I came to London I already knew chords, it just meant learning some other tunes, and because my dad had given me a record player and I had access to all his records and I used to spend my pocket money buying Beatles and Small Faces, The Foundations and Clem Curtis’ [sings] Build Me Up Buttercup and tunes like that that. I was interested in The Who - Can’t Explain, or Satisfaction by the Stones and all these tunes, to stay abreast of my mates at school. They’d go “Can you play that?” and I’d go "Yeah!” and then I’d go home and instead of homework I’d do some homework learning the tunes.

I guess the Bajan beat Spouge arrived in Barbados after you’d left?

Yes. What happened was Jackie Opel and the Draytons Two and them lot were creating this beat. The famous tune called Drink Milk was created with that beat. But I’d gone. I was already way into ska and Desmond Dekker, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, and The Beatles. I kind of didn’t listen to any Caribbean music for a while, not for my own pleasure anyway. My dad listened to everything from Jimmy Smith to Count Basie, to Stevie Wonder to Otis Redding. He also bought The Beatles She’s So Fine and Money because my young sister liked them. My sister also liked Shirley Bassey. I kind of stumbled on Jimi Hendrix and thought “Wow! If I could play the guitar like that!”

I guess a lot of people had the same experience.

I came home from school and the phone’s ringing. My mate Tony says “Are you watching Ready Steady Go?” I get it on and there’s this guy eating the guitar! I mean really like playing with his teeth. Jimi Hendrix on Ready Steady Go doing Hey Joe. It really was electric. Before then we were playing a bit of 1910 Fruit Gum Company, and Monkees and tried a bit of Cream, and Small Faces. We kind of went from there into Jimi Hendrix. After a while we started going back to the blues and rediscovering BB King. Before that I’d been a real Bill Doggett fan, so I’d learnt all the notes to Honky Tonk and amazed kids going “Wow, he can play that!” I spent hours in my bedroom with the guitar and my dad’s 78. I slowed it down to 45 and learnt it in that key. Once I knew the notes I put it back to speed and I learnt it in the right key.

Studio 1 pianist Richard Ace told me that tune was really important for the coming of ska…

Yeah! And lots of Fats Domino tunes as well. And Rufus Thomas, was it Walking The Dog? One of his dog songs… because he had Can Your Monkey Do The Dog, Walking The Dog, and The Dog Revisited [Somebody Stole My Dog], didn’t he? (laughs) He was the original dog man! One of his tunes, the intro of it was like [does intro to Carla & Rufus Thomas’ Cause I Love You], the one they use for Oh Carolina. They nicked that intro off of a Rufus Thomas tune.

You went to quite a musical school in Wandsworth.

You went to quite a musical school in Wandsworth.

Yes, Spencer Park in Wandsworth had the full orchestra. The music classes there were severe. When lots of other schools didn’t have music as a career, my school did. Also sound engineering was part of the syllabus. They even did bricklaying and carpentry, as well as science and maths. It was one of the first Secondary Comprehensives in this country where you didn’t have to do an entrance [exam] because it wasn’t a Grammar. Once you got there, if you wanted to be a sportsman they would notice that earlier on and then channel you in that. I was into music and art, so they just showed us the way to get into that. But they also said “You ought to have something to fall back on” so I was learning to be a contact lens technician, making contact lenses. It was quite a technical, intricate thing; measuring using the old scope, trying to get the right power, grinding lenses, shaping lenses. I went through the whole process of making a contact lens from a piece of plastic in the lathe, until you’ve got something very flimsy that’s going to go in someone’s eye. It’s got to be made with such precision. I quite enjoyed that.

How come you became a full time musician instead of doing that?

I did two years of a five-year apprenticeship. Because I was that keen on it I learnt the job and in two years was doing the same thing as people who’s been there for five years – so I went to the boss and said “How about upping my wages?” and he said “No, no, you signed a contract”. So I was like “What? I have to work for boy wages for the next three years, but doing a man’s job?” and he was like “That’s the way it goes!” So I thought “Hey, it’s about time I went out and did a few gigs for my sound system and with my band” (laughs). But I couldn’t hold down the two. I’d be going up and down the motorway with Matumbi and getting back at like 5 or 6 in the morning and having to go to work at 8.30, it was like urgh!

SOUND SYSTEM

By the early 70s while you were getting somewhere musically with Matumbi you were also on the rise as a sound system selector with Sufferers Hi Fi. How did you get into sound system?

At school, in the school studio I’d make dubplates to sell to the local sound systems, Jim Daddy, Duke Reid, Coxsone, Rocket 69. Another little thing I had going was they used to have these blues dances and they’d print invitations on these really, really frilly cards, kind of feminine looking. There was a printer who had a business near my house and I’d go to him and buy these cards and print these invitations to blues dances using the school press. One of the things I did in art was typography, so I learned to do typeset and we’d print Spark, the monthly school magazine. Having the knowledge to typeset I’d just lay a few lines and run off 150 cards or something (laughs). So I always knew where the sound systems were playing because I was printing the invitation cards. People would go “Oi, where’s so and so playing?” and some of these cards, you’d have to have an invitation to get past the door, so I’d just print a few for my friends and go “Yeah, go on!” (laughs)

How did you start cutting dubs for the sounds?

I decided that we could use the school studio to do recording, to make dubplates to sell to the sound systems, exclusive specials, so went into that as well. Once I’d recorded a few I needed someone to cut them, so I found this guy called John Hassell in Barnes and he offered to teach me about disc cutting if I helped him do his mobile recording. His eyes weren’t very good and his wife used to drive him, but his ears were immaculate and he could hear everything. I used to go with him on Saturdays and Sundays, he recorded Jasper Carrott when Jasper Carrott was a folk singer and things like the Latvian Song Festival at the Royal Albert Hall. We went in there to do that with a 500 voice choir. John’s got his recorder out, we’ve gone there early and he’s traced all the wires and he’s going “Right, I’m having that one, that one, that one…” and he’s found the wires that the BBC have got for stereo pair microphones, 50 feet in the air, left there for their recordings. John just found where you could source them and plugged into there and used the BBC microphones to do his recordings. He was that kind of cheeky chappie, you know? He was one of the directors of Capital Radio. David Rodigan lived in the same street as him, so David used to come by.

This was when he was working at the brewery in Chiswick?

Yeah, right. And then he got a job and he was acting at the Royal Court, and all that time I was friends with him he used to come down and we used to give him dubplates because he was very curious about what was happening in John’s house. In fact one day John said “Here, I’ll give you a tip. David Rodigan’s going to get a radio show” and the rest is history! (laughs)

How did you end up becoming a selector on Sufferer’s Hi Fi?

I’d made all these dubplates and I met an old mate from school called Owen who said his cousin’s husband was building a sound system and they were after some dubplates. So he came round my house and I played my collection to him and he went “Yeah, I’ll have that, and that, and that…” and bought the whole selection. So I was like “You’re making a sound system. Perhaps you need a DJ” and he went “Yeah, yeah, we need a DJ and that’s you”, so I was in and then I was sort of straddling the sound system world and the groups world. At that time sound systems were much more popular than groups, so to get into sound system was quite difficult. I mean they had heavyweights like Coxsone, Duke Reid, Count Shelly, Fatman, Neville the Enchanter, all the big heavyweights, and then then was us: Sufferer, little sufferers, right? (laughs) So we had to make a name for ourselves. We started playing in a club called the Lansdowne in Stockwell and quickly would get hundreds of kids in on a Sunday night.

How did you get a spot at the Metro club?

The guys running the Lansdowne got a call from the guys who were running the Metro in Ladbroke Grove who asked if we would like to do a residency because Duke Vin had just been shut down there by the police. The selector and a couple of other people had got put in jail, there was an affray of some kind. So Metro was sort of rebooting and the guys who were asked to do it were a soul sound and they said “No, no, no. Ladbroke Grove is reggae territory and we’re not going to play soul over there because no-one will come”. So we said “We’ll do it” and within a month we’d built up a really heavy following there and it was the happening place. Then we moved to the Carib Club on a Friday night and we played Whisky A Go Go in the West End on a Saturday. Then there was a place in Fulham, a school hall, then we played in the Crypt on Wednesdays in Battersea. So we had almost a full week and then sometimes at weekends we’d go and play in Birmingham or Leeds or Manchester or occasionally we’d have seaside excursions where we’d rent a couple of coaches. The sound quickly got really big.

So you were holding your own in both when sound clashing sounds and also playing live music in clubs like Four Aces, were people could get a rough reception. Would you say that doing these things well came down to confidence or knowing technically what you were doing?

Mate, both. You had to have the confidence to want to do it in the first place, and you had to have the technical ability to do it. My mate Errol Francis was an electrician and he also did private work like rewiring people’s houses. We helped him, there was a posse of us who did the manual work like digging the holes and tearing the walls down and tearing the wire out, and he was a qualified spark. He got a job to rewire the Barbados embassy and made a few quid and decided that he was then going to invest that money into a sound system and get some amplification. So he’d do jobs apart from his own job and we’d help him and he’d give us a bit of money and we’d buy records and amplifiers and turntables and vehicles to move around in. The sound wasn’t making money to pay a wage for everybody but it was making enough money to buy records and it meant that we didn’t have to put our money into it. It was kind of paying for itself and it was good entertainment for the lads, out for a night and listening to some tunes. Then there was the pride of playing in a place with Count Shelly and suddenly Shelly goes “All right, I’m not going to play anymore, you lot carry on for the rest of the night”, not admitting defeat but kind of thinking he wouldn’t have done that if we weren’t good enough.

Did not being Jamaican make any difference at that point? Did anyone care?

Close friends knew, I suppose everyone else just presumed. I was of the opinion that “If you don’t know me, you don’t have to know my business”. People that know me know that. I acquired a hefty Jamaican accent because of working with all these Jamaicans, you know? Actually the only other person from Barbados that I knew as a musician was Jimmy Haynes, and Eddie Grant was from Guyana. In the sound world there were hardly any non-Jamaicans. There were a few but the sound system world was mostly a Jamaican thing and the music certainly was. Occasionally you’d get a soca tune or James Brown or Kool & the Gang or Aretha Franklin, but predominantly reggae would be the thing and we immersed ourselves in that culture.

You’ve gone into some detail in Lloyd Bradley’s book Bass Culture about how you came to spend six months in prison for “causing an affray” after a raid on a dance at the Carib Club in Cricklewood in 1974 – but you weren’t actually arrested on the night.

You’ve gone into some detail in Lloyd Bradley’s book Bass Culture about how you came to spend six months in prison for “causing an affray” after a raid on a dance at the Carib Club in Cricklewood in 1974 – but you weren’t actually arrested on the night.

I wasn’t arrested. Well I suppose I was technically, once I was charged, but what happened was after the fracas I was in Ladbroke Grove and someone went “Oi! The cops are looking for you!” So I went to the police station to say “What’s this all about? I hear you’re looking for me” and they went “Yeah, come here, we want to talk to you”. And then they accused me of starting the fight which I deny to this day. Basically a policeman just went in court, put their hand on the Bible and lied.

What was it like in prison? Boring? Frightening?

Actually it was a learning curve. I had the chance to do lots of exercise and make my stomach muscles tougher than old lead. Also I had a chance to read and write songs because there was no telly. I had a chance to look into myself. I read Muhammad Ali – The Greatest. Also I started a little business in there because I worked in a warehouse where I had to paint Paddington Bears. There was a guy in that same workshop who was from another block where he had access to olive oil, so he used to bring the olive oil and I’d get it off him and flog it to the guys in my block, and the currency was tobacco. This guy was a heavy smoker. People didn’t have olive oil and we black guys used it to oil our skin and put in in their hair. I became known as the man you could get olive oil from, so there were lots of guys in prison who I knew or who knew me, either as a sound system man or as a musician.

How did being inside affect your music career?

I got sent down on the Tuesday and on the Friday Matumbi’s After Tonight was released and all the time I was in there it was being played on the radio. When Tommy Vance had that Capital radio show he was playing my tune and on the Saturday night we’d be listening to that in the nick. When it came up in front of the appeal courts they set me free. I won that. I think it was just a case of the jury being hell-bent on convicting someone, even though of the twelve people charged nine of them were farcically thrown out on appeal. My standpoint was, this is England and if you’re innocent until proven guilty, you didn’t prove my guilt and therefore I must be innocent. And the judge went “Yeah, that’s what you think. There’s going to be a retrial”. They retried me and two other guys for a crime that was supposed to have been committed by twelve people in the first place. I don’t know really how it even got to that. The police fitted up a lot of evidence, for instance the policeman that identified me said that he came in and had all the lights on and I was standing on the stage with a microphone in my hand geeing up the crowd, and that never took place.

Someone else had the mic?

Oh yeah, but I weren’t telling them who it was! (laughs) It weren’t me!

MATUMBI

So while the sound system thing was going along what was happening with Matumbi?

The group was coming along, we were writing a few tunes when suddenly I got a break where Lloydie Coxsone said “I want to do a reggae version of this tune” and that tune was Caught You in a Lie. I did that and it became really, really popular. So then I was kind of moving out of the sound system world and moving into the recording world, group writing songs and touring with the band. In the interim Pat Kelly had asked Matumbi to be his backing band, so we did that, then we backed Johnny Clarke, I Roy, Ken Boothe, Derrick Morgan, and Nicky Thomas. Then we got a sort of record deal with Trojan, made a couple of cuts and fell out with them quickly.

In Matumbi you supported the Wailers. What was your take on them?

I’ve always been a big Wailers fan! I can’t comment on them as people because I don’t know them as people. I’ve met two of them. I never met Bunny Wailer but I met Peter and I met Bob. I met Bob when he was doing Exodus and I met Peter when he was doing that thing with Mick Jagger.

But it was all three of them when you supported them live?

They were all three together at the Sundown in Edmonton - that shop there that’s now a Lidl. We knew we were going to be on the same gig as them, so we did a lot of rehearsal and we had a sound engineer. They were relying on the engineer of the house, they didn’t have someone working the boards specifically for them, but we did because we were so scared that we were going to sound crap that we rehearsed up until about two hours before the show. Also at that time we had a single out on Trojan called Reggae Stuff. We’d done a version of a Kool & the Gang tune and it was our single, so we had to perform that properly. We recorded that at Morgan’s which is now Assault & Battery [Studio] in Willesden.Our keyboard player Nick Straker just graduated to Hammond whereas before he’d been playing on a Vox Continental, so we had to work with that because there was an organ solo in the tune (laughs). So we’re like “We’re playing and the Wailers are in the show, so we’re not going to be booed off!” It was a benefit for Ethiopian famine relief. We went on nervous but rehearsed. We did our set and it got well applauded and everything went without a hitch, but when the Wailers came on there were some glitches in the PA system and there was feedback. Nobody likes feedback and as soon as you hear feedback it puts a dampener on things. I personally think it was because the stage was probably too loud, and we’d learnt not to have the stage loud.

But you didn’t interact with them at all? They just showed up and did their thing?

No. But our drummer was at school with Bob in Jamaica. When we formed Matumbi I knew this guy called Euton Jones who used to have a group called the Gladiators. Not the Gladiators but a group called the Gladiators in London. Him and another guy called Earl Matthews. And another guy called Eric Able - him and Michael Bruno, Frank Bruno’s elder brother, had a group called Black Volts. These guys were older than me – when I was like 16, they were 25. Sometimes I could fill in with them on keyboard when they had this soul band and they played at the Greyhound in Fulham on a Sunday night. Euton, the drummer, liked me. I was a younger kid hanging out with him.

How did Euton join the band?

How did Euton join the band?

I said we were going to do a reggae band. Before that I’d had a pop band, a blues band, and a progressive rock band. So I was like “We need a reggae drummer. Everything else is fine, guitar, keyboard, whatever, but to play well we need a reggae drummer” and I knew one and it was Euton Jones. I also played drums in a rock band at school, so I went round his house and borrowed his drum kit. I sent him a message and said “We’re forming a new band. It’s going to be a reggae band and you’re playing drums. If you don’t come to rehearsals you’re not getting your drums back, I’m keeping them”. He laughed his head off and was like “You, you little scamp!” Obviously he could have kicked my head in but it was to say to him “Look, this is going to be important” and he liked me because I was quite cheeky. He played drums on Caught You in a Lie, on After Tonight, Man in Me, Chatty Chatty. He was like an elder person who knew how to do the one drop without us having to tell him. All we had to do was keep up our end of it. So he became the drummer in Matumbi, so we had a head start in an older drummer who could play reggae.

Was the key to your success in Matumbi that you had a wide musical palette while also being able to play reggae properly? There must have been other people who were adventurous but didn’t get the beat?

That’s right. And I could lift things from my Beatles or Monkees pop culture or from my Otis Redding or James Brown and incorporate it into reggae. For instance when I first thought I was going to use a wah-wah pedal and a fuzzbox in Matumbi the lads are going “Where are you going with that? This is reggae and you’re supposed to go ‘tchick-kik, tchick-kik’ and be done with it” I was like “And what about when I need to do my solos ‘whaah-wah’?”, “Oh bloody hell, you don’t need all that! Why don’t you just play a nice solo like Hank Marvin?” And I was going “No, why can’t I do a solo like Jimi Hendrix? With some feedback or something”, “That’s too wacky, man. People are not going to like that”. So I thought “Well, I’m going to do it anyway”. If you listen to Chatty Chatty or them tunes I’m playing what I thought was some pretty good guitar. Then I met John Kpiaye and I heard him play guitar and I thought “Oh no, I’m never going to be as good as him!” So I invited him to be the guitar player in my band.

What was behind Matumbi’s acrimonious split from Trojan? Different things have been written about it. Some books have said things about solo projects, some about cover versions.

They treated us badly. We wanted to write our own songs, and we did. But they thought that our songs weren’t all that. Even to the point that someone ripped off our intro to the tune we wrote about Enoch Powell [sings Go Back Home]. The intro of that tune miraculously is the same as Everything I Own. I wonder how that came about! And ours was recorded well before. Ironically enough, we backed Ken Boothe before he’d done Everything I Own. Then we stopped when Everything I Own was a hit because there were financial arguments and we refused to play in a show one night at Hammersmith Palais until we got paid. Then they paid us and then they went to get Cimarons to back Ken Boothe, but we didn’t care because we’d had enough. We’d done the tour and then suddenly he was going to go Top of the Pops and it was like “Are you going to do it?” and we went “No!” (laughs) And they got Cimarons to do it and that was the end of our relationship. We didn’t get to be on Top of the Pops until Point of View.

So then you linked up with Lloyd Coxsone to release several big tunes through him.

Correct, and did Caught You in a Lie. That was at the same time as After Tonight. If you listen to those two records they sound the same, just a different singer. That’s because I’m the bass player on both tunes and I’m also the guitarist and the keyboard player, and the drummer is Euton Jones on both records. We were a kind of a two-man band. We were members of Matumbi, but Matumbi as a band didn’t play on those records, so the sound of Euton and myself is: Caught You in a Lie, After Tonight, and the Man in Me. Those three records, they sound exactly the same because it’s the same players, him and me, with different singers. Me on the bass, him on the drums, me on the keyboard.

When you did the Man in Me, had Freddie McGregor already done I Shall Be Released on Studio One? Had you even heard that?

Freddie McGregor? But that was not like the Man in Me.

I know, but it’s Bob Dylan.

Oh, oh, oh! That tune! Bob Dylan’s the writer, yeah. Yeah, he probably had done that before. That Man in Me tune, I heard it from the Persuasions. I didn’t even know it was a Bob Dylan tune. I heard the Persuasions do it on their Street Corner Symphony album and I liked the tune, but I changed it around and faded it out so that it could go for three minutes, because if you listen to the Persuasions version it goes [sings] “Never found a lover after loving you-oo-oo” and I thought I won’t be doing with all that, I’ll just have that song. I didn’t know it was a Bob Dylan tune until someone said “Hey! Listen to Bob Dylan’s version of it” and it’s completely different. Freddie McGregor recorded our version - well Jet Star did. I phoned up Jet Star and said “Where’s my arrangement rights on there? You’ve done my arrangement of that song, so it should have ‘arranged by me’ on there right?” and I kicked up a stink about it, but they folded anyway.

READ PART II HERE