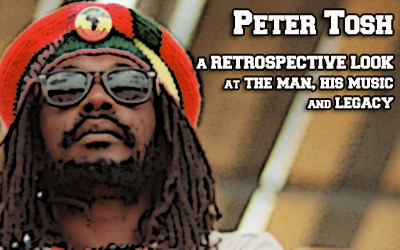

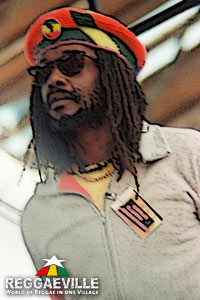

Peter Tosh ADD

Peter Tosh – A Retrospective Look At The Man, His Music & Legacy

10/19/2011 by Stan Smith

"I want people to get sensitive to the music…if you’re not listening to the message of the music it’s like a fool dancing to calamity” ….Fool dance to comfortable promises" – Peter Tosh

Peter Tosh would have been 67 on October 19. 2011. It has been 24 years since one of the worlds and reggae music’s greatest artists and most articulate and influential voices were silenced by an assassin’s gun.

The government of Jamaica has yet to honor him with a national award for his monumental contribution to the development of Jamaica’s reggae music. Nor, have they seen fit to highlight his achievements. Tosh was recently profiled in the United States on National Public Radio. NPR is the equivalent of the BBC in England. He has received many honors from around the world including a Grammy award in the United States for his timely 1987 album “No Nuclear War.”  The album reflected his concerns about the cold war tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was timely because in the mid 1980’s Europe erupted in massive demonstrations over United States president Ronald Reagan’s, Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s and NATO’s decision to deploy SS20, Pershing 2 and Cruise Missiles in West Germany. In the United States, the ‘Sun of Reggae’ was also presented keys to cities where marijuana is decriminalized, like Atlanta, Brooklyn, New York city, (he accepted at steps of City Hall with his ‘spliff’ in tow) and also Nigeria.

The album reflected his concerns about the cold war tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was timely because in the mid 1980’s Europe erupted in massive demonstrations over United States president Ronald Reagan’s, Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s and NATO’s decision to deploy SS20, Pershing 2 and Cruise Missiles in West Germany. In the United States, the ‘Sun of Reggae’ was also presented keys to cities where marijuana is decriminalized, like Atlanta, Brooklyn, New York city, (he accepted at steps of City Hall with his ‘spliff’ in tow) and also Nigeria.

The history of reggae music – or the reggae story, and its importance – is invariably and inextricably linked to the Wailers: Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer and Bob Marley. They single-handedly transformed what popular music could be used for as an instrument of liberation. As the Wailers, they created a complex music, reggae music, and redefined popular culture by shifting the focus from words and melody to concerns with the realities of the poor and oppressed and their quest for equal rights and justice.

Peter Tosh, the musical artist and Pan Africanist Rastafarian, is a fascinating study in contrast, because, like most revolutionaries, he was a multi-faceted and complex human being. As an authentic artist who rose from common culture, Tosh's importance as a world figure, for me, occurred when as the first reggae artist, and possibly the first western artist I can remember, he highlighted and then educated us about the evils of apartheid as a political system. On his 1977 epochal Columbia Records album 'Equal Rights', Tosh details "apartheid inhumanity." With his mantra of “Equal rights and Justice” Tosh challenged the world community to end apartheid. More importantly, this was done before apartheid became a fashionable political issue. Many were surprised at Tosh’s grasp of this unpopular issue so early before this issue penetrated the public consciousness.

I had the good fortune to produce and host four retrospectives on the life and times of Tosh on "Reggae Roundtable" hosted by Habte Selassie on his programme, Labrish, which aired on WBAI 99.5 FM in New York. The guests included Tosh’s former bandleader and Chairman of the Jamaica Association of Artists and Performers, Steve Golding, dub poet Oku Onuora, musician/producers Sly and Robbie, former manager and lecturer, Herbie Miller, musicologist and Director of Reggae Programming at XM Satellite Radio, Dermott Hussey (who visited Brazil with Tosh in ‘83), Fikisha Cumbo, (who had a nine-year association with Tosh and is the author of ‘Get Up Stand Up: Bob Marley and Peter Tosh’ and radio personality Karl Anthony. A deeper understanding of him and his work could help to accord Tosh his rightful place in history. Peter Tosh should be honored.Peter Tosh was musical pioneer, a multi-faceted musician, singer, song-writer, composer and performer. Writer Mat Cibula described Tosh as "truly one of the great lyricists of modern times." He was also an authentic political revolutionary artist whose political ideology was Black Nationalism or Pan Africanism. Tosh espoused his Rastafarian views through his music. Described by Rolling Stone magazine as reggae’s Malcolm X, Tosh has been compared to John Lennon for his cynicism and artful use of word play, however according Matt Cibula, “Lennon’s weak and passive Monty Pythonisms pale beside (Tosh’s) holy wrath.” Peter Tosh was forced to work against bruising criticism and misunderstanding from his own people who failed to recognize his accomplishment and greatness. While Peter was clear about what he wanted to do the implications of his work was far less obvious to some of his critics because they couldn’t interpret him or his work, or chose not to, whether by design, or inability tended to not explore Tosh, the man and his mission with any great depth. A purposefully melancholy soul of an artist, Tosh, was a simmering cauldron of righteous black anger for his oppressed generation because the central focus of his musical activism was human rights. Peter’s vitriolic and incendiary speech at the historic ‘One Love Peace Concert’ in 1978 is a classic example. It was, arguably one of his finest moments of his onstage career.

While Peter was clear about what he wanted to do the implications of his work was far less obvious to some of his critics because they couldn’t interpret him or his work, or chose not to, whether by design, or inability tended to not explore Tosh, the man and his mission with any great depth. A purposefully melancholy soul of an artist, Tosh, was a simmering cauldron of righteous black anger for his oppressed generation because the central focus of his musical activism was human rights. Peter’s vitriolic and incendiary speech at the historic ‘One Love Peace Concert’ in 1978 is a classic example. It was, arguably one of his finest moments of his onstage career.

How important was Peter Tosh in the history of music, and what is his contribution beyond the world of music? Tosh as a serious, politically committed artist, both solo and as part of the reggae triad, the original Wailers. He, Bunny and Bob, exerted a powerful influence on society. Tosh’s influence went well beyond music to politics, religion, liberation theology, anthropology and culture and has become a part of more than just music history. Tosh had a finely-tuned and discriminating understanding of his role as a political man. Because he came from the bowels of poverty and oppression, from a place University Lecturer Carol Cooper described in the Village Voice: “The ghetto in Jamaica is… an area where black people live without the social connections to advance to upward mobility. It is here the (1) “inborn talents”…are “neglected and rejected for reasons of color or poverty.” Peter was about getting black and oppressed people to realize who they were, and, at a given point in time in their history, how they got to be where they were, and more importantly, where they needed to go and how to get there.

The misfortune of this seminal artist, who was one of the giants of music, is that in his prime, his resonant voice was stilled when it had so much more to say. As a deeply spiritual, yet feisty and fierce, revolutionary political activist who was ready to die for his unpopular convictions, this complex freedom fighter and warrior artiste had few equals in his time. He remains for many, a salutary, misunderstood, controversial and complex figure. He was a controversial figure because of his political radicalism and his unceasing championing of equal rights and social justice as well as the legalization of marijuana. Tosh's talent, greatness and musical achievement have gone largely unheralded and his music has yet to receive the acclaim it so richly deserves. Why he is not celebrated and honored in Jamaica?

Despite Tosh’s accomplishments as a solo artiste, his voice and perspective is rarely ever written with the prominence ascribed to Bob Marley. Yet, his work was equally important and Peter is “Just as much an architect of reggae music” as Bob Marley is. Tosh summed up his life’s mission this way: “Reggae is spiritually revolutionary, and the message is divine. The message content opens the eyes of the people to the evils of the system… inside the music are the seeds of destruction of the said system. But the music, like a germ, is contagious, so it must germinate and all the guardians of the system can do is delay the process… It must happen! The system must explode from conflict, modify to accommodate the pressure or transform to a brand new day.”

His critics did not write much by way of in-depth critiques or analyses of Tosh's ideas and philosophy. Not many sought to go beyond the fascination with the exotic myth of the “noble savage.” It became all too "easy to be absorbed by the novelty of Peter Tosh's culture and forget that he has his own ideas" and it was also easy to dismiss the reality that these ideas were rooted in political, cultural and religious philosophy. As Carol Cooper noted in the Village Voice "Critics raved about the imagery and spectacle of Rastafarian music without ever touching on the heart of the message." This is part of the reason the media and others rarely asked Tosh serious questions. Nor did they probe beyond his public persona to find out who he was, or what he was trying to accomplish. Tosh was as well-read as he was articulate in his advocacy of the issues he believed in. His drummer Santa Davis stated, "Peter used to read a lot of books, like, intellectual stuff, deal(ing) with world (issues)" and according to engineer Dennis Thompson, "Bush’s” (as he affectionately called Tosh); house was always filled with books because he read a lot."

Tosh had an intelligent and informed grasp of world issues he considered important. This included a very astute understanding of the role class and race issues played in the discrimination against blacks and oppressed people living in impoverished in Jamaica.

Sly Dunbar, who recorded and toured with Tosh's band in the 1970s, told me on a 1996 edition of my "Reggae Roundtable" special on WBAI, that he was amazed Peter knew about apartheid in the early ‘70s. "The things Peter use to talk about, although we didn't understand at the time, all come to pass. It was like, he was seeing ahead of all of us." His knowledge of apartheid was so thorough, yet none of his peers or brethren had ever heard the word, much less knew what it meant at the time.

Critic Stephen Davis’ questioning of Tosh about the beating he took at the hands of Jamaican police is an example of how little Tosh and what he was fighting for was understood. Davis asked Tosh if the police knew who he was and the fact that he was international celebrity, implying that this somehow might have made a difference in the way Tosh was treated. Peter replied "you don't have to know a man to treat him the way he should be treated. Because I don't ... drive a Mercedes Benz, I don't look exclusively different from the rest."

Critic Stephen Davis’ questioning of Tosh about the beating he took at the hands of Jamaican police is an example of how little Tosh and what he was fighting for was understood. Davis asked Tosh if the police knew who he was and the fact that he was international celebrity, implying that this somehow might have made a difference in the way Tosh was treated. Peter replied "you don't have to know a man to treat him the way he should be treated. Because I don't ... drive a Mercedes Benz, I don't look exclusively different from the rest."

Davis’ implication missed the point by his assuming that had the police known Tosh's status they may have been inclined to be less brutal. What Davis failed to grasp is that, at that time, blackness of skin was treated by the society as badge of inferiority and the celebrity culture of entitlement was not what Tosh and his revolution was about. For Peter the fact that he was an international celebrity shouldn’t be the reason he was treated differently. He saw his mission as fighting for the common man, who he saw himself as part of. He sought too, to have his humanity affirmed. In other words, one need not be a celebrity for your basic human rights to be accorded you.

For art to be valid, it has to make a social statement or advance such concepts in more important ways. Art without a socio-cultural context is useless; therefore there can be no such thing as an artist who is divorced from his social context. Art is the artists’ expression of his vision, social context and his socio-political circumstances and cultural milieu. Langston Hughes in his essay ‘The Negro and the Racial Mountain’ wrote about the obstacles and pressure the black artist faces in being true to himself and his racial identity. The black artiste, whose work must, like all true artists reflect his life experiences, is instead forced into the false option of being just an artist. In a racially discriminatory society, black skin proved be an impediment to civil and social equality, claims to black individuality were ignored, and their indigenous language and culture marginalized and suppressed, which creates the "urge towards whiteness." Peter Tosh was forced to work against bruising criticism and misunderstanding from his own people. This is mountain Tosh as a true artist had to climb. Tosh was an artiste of the common people and through his assertion of his cultural identity he was never afraid of being himself. His was comfortable with his Africanness and he was able to maintain his own individuality as he developed his art and became a great artist.

Let’s celebrate this great warrior and musical pioneer and hope the government of Jamaica will recognize and honor him for his achievements. It is time for the government of Jamaica to recognize Peter Tosh’s important contribution as reggae music’s Black Rebel Prince’ and his distinction of being reggae music’s most influential stylist, with a national honor in recognition of his monumental contribution to the development of Jamaica’s reggae music.