Lone Ranger ADD

Lone Ranger Interview - From Studio 1 to Sunsplash

04/03/2020 by Angus Taylor

At the turn of the late 70s and early 80s, the deejay phenomenon was bubbling on sound systems in Kingston, Jamaica. As roots reggae began to shift towards what would become dancehall, the sound of the day was a pleasing combination of microphone lyricists chatting in wide-ranging and humorous fashion over reggae rhythms played on live instruments.

One of the more influential and inventive exponents of this re-alignment was Lone Ranger. Harking back to the way U-Roy had galvanised deejaying at the start of the 70s atop repurposed 60s Treasure Isle rhythms, Ranger brought a similar breezy melodious flow to augmented Studio 1 backings, adding his own infectious vocal dancehall gimmicks.

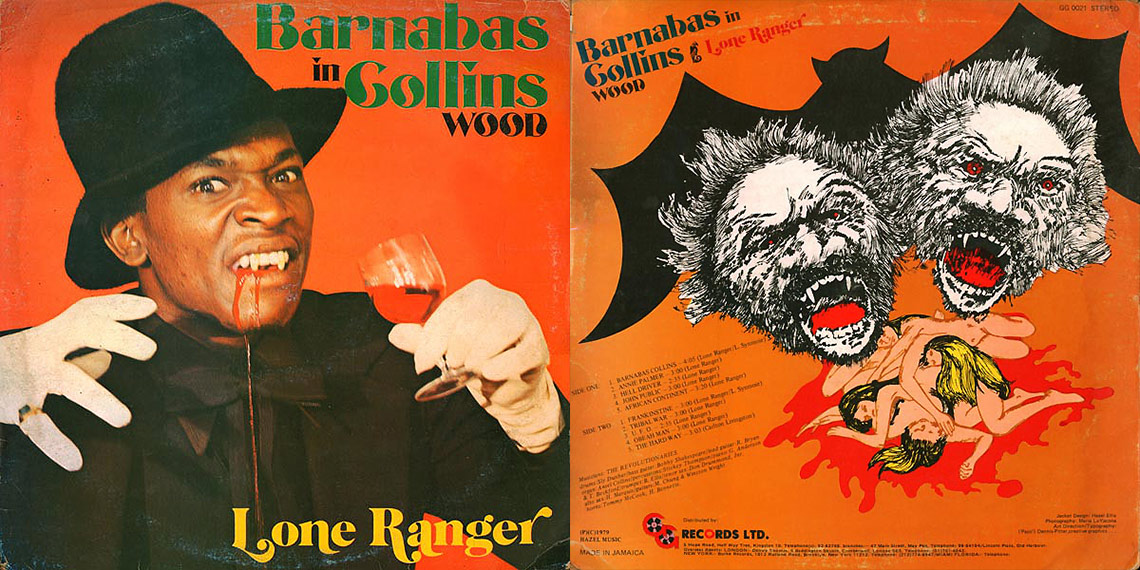

Born Anthony Waldron, the young Lone Ranger grew up briefly in Kingston, spending a large portion of his childhood in London. On returning to Jamaica, he tried his voice at singing before switching to deejaying and becoming a rising star on the local - and then national - sound system scene. He learned his recording craft at Coxsone Dodd’s Studio 1 Records, which yielded him multiple Jamaican hit singles. Meanwhile he was making waves in England with debut album, Barnabas Collins, produced by the Synmoie brothers and distributed by Alvin GG Ranglin, featuring its iconic cover of Ranger dressed as a vampire.

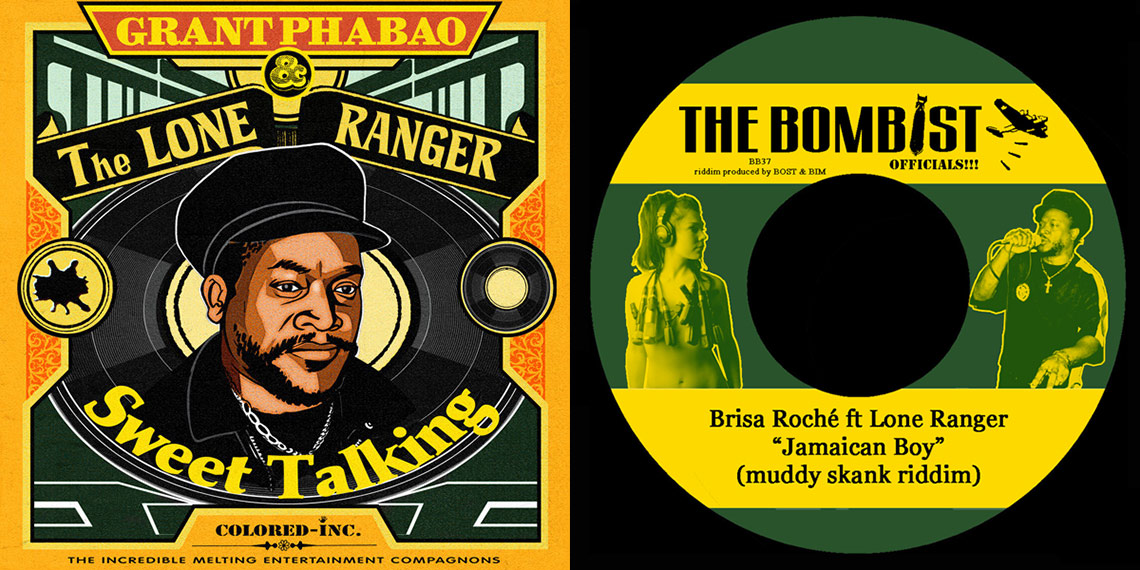

As his fame rose, he began travelling to Europe and the USA during the mid 80s, settling in New York until a second return to Jamaica in the late 90s. In the new century he has continued to keep links abroad, releasing albums with producers Bost & Bim and Grant Phabao (France) and Tandaro (Germany).

In person, Lone Ranger has a similarly world-weary laconic humour to his favourite singer as a youth, Horace Andy. Like Horace, he is not a prolific giver of interviews, only agreeing if it is suggested by someone he trusts. In this case, it was his old friend and sound system spar from East Kingston, Carlton Livingston - who was over from New York visiting Jamaica at the same time as Reggaeville’s Angus Taylor.

Ranger drove up to Carlton’s dwellings in his car, sat in an armchair and announced that he didn’t really like interviews, suggesting that both time and topics would be limited. Yet he spoke happily about his beginnings, his influences, his relationship with Coxsone Dodd, and his experiences as a child of immigrants in Britain, which sadly, ring all too true today...

You were born in Whitfield Town?

Yeah, call it that, Whitfield Town or Rose Town.

But you went to England for a while?

Yeah, in 1963 my mother was up there and she sent for me. She had three boys. I'm the small one and in 1963 she decided to send for her kids. I lived in Tottenham. N17, Park Lane, White Hart Lane, North London.

What was it like growing up in England in the early 60s?

England is nice. I love England but the only problem was in the 60s the racial thing was up. Up up, real up. Because even me, I had problems going to school all with the skinheads and all that. My brothers them, they could always fight. They would carry me to school and pick me up.

Is it right that you went to drama school?

Yeah man. That was in England too. Because once you were in England, the schools there, drama is a subject, swimming is a subject, everything is a subject. Not like Jamaica where swimming is there but they don't care about it, if you want to do it, you do it. In England it is a subject so you have to take part. So I was doing drama for a little bit, standing on stage reciting poems and acting. So all that was in me from early.

I guess not only did that help you perform as a deejay but when I think about the album cover for Barnabas Collins, it's quite theatrical…

(laughs) Yes! It was drama, yes!

So how come you came back to Jamaica?

Well after a while it was getting really really hectic, for even my mother. Because my mother is a nurse, you know? And in England in the 60s, yes, you had the Conservative party which is not really for the black people. You had man like Enoch Powell shouting “Blacks go home, niggers golliwogs” and all that - willing to pay your fare back to Jamaica but if you take that money there you can never come back to England. So my mother didn't even deal with that. She just booked her ticket, her passage and we took a ship, the Begona. A Spanish liner from Southampton all the way back to the Caribbean; Caracas, Venezuela, Tenerife, Trinidad, Tobago, right back to the Kingston harbour. This was in 1971 we reached back.

How quickly did you find your way onto sound systems when you came back to Jamaica?

Well it wasn't much too long. Because when I came back back in ’71 I just came back and got into school, everything was new, you’re listening to the radio, there is reggae going on. I'm hearing all sorts of artists from the 60s. Because my mother used to keep house parties in England. So I came back to Jamaica and I'm hearing this new sound and this deejaying, this U-Roy, this Big Youth, I-Roy, Jazzbo, Dillinger all these artists. And it sounds good to me.

So what I did now was when my mother would take me to school, I’d take my lunch money and when I would leave school now I didn't bother to eat lunch. I shared my lunch with somebody so I saved my money and I’d walk downtown to Randy's Records or Joe Gibbs and buy all the latest U-Roy and all the latest Big Youth and hide it in my bag and go home. And when I’d get there I’d turn on the stereo and play the part one and write it out. And it being in the 70s you would flip it over and the version is there so I would write out the A-side and rehearse on the B-side. Perfect. I’d just keep that to myself until one night we started to go to parties in my area. Ellison school used to have a sound named Merry Soul and I used to deejay one or two songs around there.

And then, you know, Arrows was the king in our area, in the east, and we used to listen to Arrows. Because I used to go Vauxhall and Vauxhall playground was adjoined to the backyard of Arrows International. So if Arrows was testing the sound you could stay in the schoolyard and hear it, so there was a crowd listening to music.

Is it right that you were a singer before you were a deejay?

Well after that now, it was me and Carlton up in Franklin Town. Because in that time Arrows deejays were Puddy Roots and Crutches. So in those times we really didn't have the name yet. I was going by the name of Jah Waldron and Carlton was the Original Postman (laughs). So we just draw out our thing on [our sound] Express with Carlton, Noel Smith and the next man, running a little champion sound and Carlton would deejay and I would sing.

My favourite singer in that time was really Horace Andy. I used to buy all of the Horace Andy them, and do the same thing, write them out, study them and rehearse on them. And so when I started to go on a little area sound and start deejaying I sounded different. And everybody was wondering why I sounded different? And the reason I sounded different was through I did grow in England and I have the English accent and when I speak you can hear every word I am saying clearly. It was a plus for me. And then through I liked to write poetry and write songs, you know I'm a writer, I stick to the topic from start to finish.

And I got into it, that was my groove and everybody was loving that style until Express boom! Big, nice and controlled East Kingston and mashed up the place! Franklyn Town, Rollington Town, Vineyard town, Rockfort, Mountain View, Raetown, Southside, Allman Town, the whole East Kingston, Wareika Hill, me have that locked. And the other sounds were there like Stereophonic, Arrows… But what got me ahead now was in 1979 that Barnabas Collins came out, Dark Shadows, that did it. That one set the foot right in.

Before we get to that - can you tell me about your brief recording career as a singer?

(Laughs) Alright, the singing career now it was my brethren Chester Synmoie and we formed a group named the I-Fenders. I was lead singing, Chester was harmonies and a male nurse from the Bellevue Centre was doing harmonies. I wrote a lot of songs and we harmonised and we rehearsed and then one day we went up to Channel One and recorded a song named Anne Marie and a song named Girls Shouldn't Stay Out Late At Night. Two songs we recorded for JoJo [Hookim].

How did you take the name Lone Ranger?

Well, it was a dance in Rollington Town deejaying on the same sound Soul Express and we were playing at a place named the Studio 1 bar. Nothing affiliated with Studio 1 Records just the name Studio 1, right on Van Street and Jackson Road somewhere right after Giltress Street there was a sound clash. I was the only deejay on Express and the other sound had about three, four, five deejays. They were all going at it and nicing up the place and then like it was our turn, our time to play. I was thinking hard and I remember the tune that Clint Eastwood did, Eastwood Is My Name. Where he said “Right now, I’m badder than Dillinger, tougher than Trinity, Eastwood is the name”. So I just took the mic and said “Right now, we're badder than Dillinger, tougher than Clint Eastwood, harder than Trinity, my name is the Lone Ranger, that's why I act like a stranger”. And the dance bust! And from that night the name stick (laughs). From Jah Waldron to the Lone Ranger.

How did you start recording at Studio 1?

In the same period of time Barnabus was doing good and then I was introduced to and was rehearsing for Coxsone now. I met a guy named Tony Walcott and Tony Walcott said “Alright now, [I want] Lone Ranger, Welton Irie, Carlton Livingston, Dexter McIntyre” and it was supposed to be Puddy Roots but Puddy Roots wasn't there… he kept missing the rehearsal! So we would do our things, riding dubplates, riding off of the rhythm, crashing here, crashing there, lose track of the rhythm.

This was done every Sunday morning after Tony Walcott came from church because he was a churchman. And they had a gramophone system, the old gramophone that he put up, up, with the Coxsone dubplate them. I can remember the first rhythm he gave us to ride was a tune named Pearl, the Alton Ellis. Man, that was one of the hardest rhythms to ride! (laughs) It was hard. But we did it and we got it and we got through and I wrote and I wrote and I got through and we firmed up ourselves.

Until one Sunday now, Mr. Walcott said “You hear me, next week Sunday, I'm going to pay Mr Dodd a visit”. I said “Alright, good no problem." So the following Sunday now, we all met up at Studio 1 and met Mr. Dodd individually. Mr. Dodd said “Ok who are you? Ok, Carlton Livingston.” Who am I? I said “Lone Ranger, Anthony Waldron”. He said “Who are you? Welton,” he said “Welton... Welton ‘Irie’... I'm going to call you ‘Welton Irie.’” So you know say Welton Irie was the first irie deejay. (laughs)

And then Mr. Dodd said to me “So Ranger, which tune do you want to choose?” He didn't pick a rhythm, he just said “Ranger pick some rhythms that you want”. So I just remember the good old Arrows Hi-Fi the big sound, they used to play some real hardcore Studio 1. These were the rhythms that I chose. And even Mr. Dodd was surprised and said “You want those rhythms there? Ok ok”. Where Eagles Dwell, Noah In The Ark, Apprentice Dentist, Quarter Pound Of Ishen - rare Studio 1 that deejays were not riding. And those were like taking candy from a baby (laughs) because I was out deejaying on sound system. I was immaculate in the soundsystem field and I was immaculate in the recording field. Everything I touched was just boom! Going, going, going.

You were on some wicked rhythms for Studio 1. All the biggest rhythms. And you made them your own. Like Answer used to be called Never Let Go but after your tune it was called Answer.

(laughs) Yeah, all the biggest rhythms. Yeah, I named them. Yeah man.

History books have said that when you came in it was like a change away from the Big Youth style more back to the U-Roy style.But you said you listened to Big Youth and Jazzbo.

Yes. All those were the apprentice parts to be a deejay… U-Roy, Big Youth, Dillinger, Prince Jazzbo, I-Roy. With a little of my originality in the mix! Until I found my real voice and the firmness, so that when I go to a dance now I can deejay like me, I can put in my little U-Roy style, my little Big Youth style and keep a dance going all night because...

Versatility.

Yeah, versatility.

So tell me a bit about the Barnabas Collins album.

Well Barnabas Collins, now, was known as Dark Shadows. Everybody in England and even in Jamaica when it touched 9 o'clock everybody's gone in, everybody watching Dark Shadows and people are scared too! It was the in thing. It was the phenomenon of that era. So I had a brother named John Steele, he's a deejay, John Steele said “Ranger, that movie series Dark Shadows, why don't you write something about it?” And he himself had two little lines to give me and I heard his two lines and I said “Wait it sounds good, ok” and I went to work, sit down properly writing, according to how I know the movie goes and that was it. Mad hit. Crazy.

Can you tell me about the cover for Barnabas Collins? How was that conceived? Because it must be one ofthe most iconic covers not just in Jamaican music but music generally?

(laughs) Yes it was! Well the cover of Barnabas Collins… I have to give credit to GG Alvin Ranglin. Because a lot of people think that he was a producer. He wasn't a producer, he was a distributor. And he had a very top photographer, Marie, I can't remember her name but she was big so he arranged for me to meet her somewhere up in Hope Road to take this Barnabas album with the fangs and the modern Barnabas drinking blood out of a crystal glass! (laughs)

So what started happening? You started touring?

Yeah. After that now Island started getting involved, Chris Blackwell got involved and at that time I was deejaying Soul to Soul. I got Deejay Of The Year in 1979, I got the the El Suzy award and then Reggae Sunsplash 1979. It was the biggest tune and I met Bob Marley there where I did Sunsplash ’79 and ’80. I opened up for ’79 Sunsplash because remember ’79 was Barnabas Collins right? Then when ’80 came around Love Bump came around and destroyed the place.

The gimmicks you came up with on Love Bump - how did you come up with those?

It came up spontaneously. Until today I can't explain it. Because when I deejay with the recording on sound system, these gimmicks or slurs, while I'm deejaying they just interject. I don't make them up and say “I'm going to do gimmicks” it just happens. It just happens. It just fits in. It's a part of the style.

What did you talk to Bob Marley about?

I didn't really get to talk to him. When the time was near they said “Ranger you have to go and line up to go on stage”. So I had to put on my Barnabas jacket and outfit and backstage I was looking and I see a white Volkswagen and I'm looking at it and I see like Bob Marley sitting in it with a baby - which I presume was Junior Gong. And so he was looking at me and he said “You alright?” and I said “Yeah” because I have a great task to face right now and the place was blocked out and my name was out there. And I went up there and did two tunes and mashed it up and the next day the Star wrote “Lone Ranger Captivates Audiences At Sunsplash”.

And this is when the world started to take notice and all producers wanted to record you...

Yes firm. The whole world. And then the tour started in France and Europe and everything. And then by ’81 Rosemarie came again and destroyed the place and all these tunes mashed up London, England, Canada, destroyed. That's when America said “Mr Ranger we need you at Madison Square Gardens.” So at that time it was me Tristan Palmer, Louie Lepke, Sammy Dread, Tony Tuff. Made a power move on the 17th of September 1981. To the United States of America.

Did you go to England? When did you go? You can hear your influence on the UK deejay thing around that time. If you listen to a deejay like, for instance, Papa Levi, you can hear the very soft, clear voice with inventive lyrics.

Yeah, clean. The first time was 1983. Same crew. Played Dingwalls, the Rainbow. I worked with Trevor Walters in the venue Balham Studio 200, David Rodigan and all.

So how come you moved to the US?

Well after being touring the US you realise that all my family, like Carlton, is in New York. My mother, my brother, my sister, kids, uncle, my niece, my nephew - everybody is in New York. I was there because of the music and other things and when I went up there now and played at the Felt Forum - all my family came. Then touring the whole of North America with Mighty Sparrow, Calypso Rose, you name the calypso kings. Me, Carlton, Louie Lepke, Sammy Dread, Tony Tuff, Tristan Palmer we all hit the road style to Canada. We went right across the North American continent and performed. So then when it was time to go back now I didn't see a reason to go back to Jamaica because I mean all my family is there. And then I went up there and started making babies (laughs), so I was just comfortable there.

What did you think about when the music went digital?

Well it was a changing point in the area but digital was ok still because we can ride rhythm same way. It's just like the same game but with different players for me.

How come you moved back to Jamaica?

Well after a long period of things I'm in America going on and going on, you know evolution, things and times change and I kind of cool out and doing different things you know? Get too comfortable, get too relaxed (laughs). Went on hiatus and then certain little things which we can't mention, so ended up back in Jamaica now and said “All right back to basics again”. I just took it from there and followed the same path and in no time - whoosh!

Because when I left Jamaica in ’81 I had about five tunes in the charts. The number one tune, the number two tune, number three, number six, number seven. Love Bump, Barnabas, Keep On Coming A Dance, Lovelorn, M16, Johnny Make You Bad So, Fist-To-Fist Days Done. Coxsone had his radio programme every Saturday morning, Sound Dimension (sings theme), all of Jamaica would wake up in the morning to Coxsone’s music. So when I came back it was like everybody said “Lone Ranger - where is he? He's back!”

Did you keep in touch with Coxsone in New York? What was your relationship like with him?

Straight through the years. That's where I was. Father son. He's a cool guy, him nice. Jovial, kind, yeah man, and he had direction. He knew the thing too. He didn't pressure you with the recording. He don't pressure you. He'd let you record and you record and when you are finished he did say “You're sure? Listen again. Make sure you're sure”. And then you do and you do over and try to fix everything that you can and he’d say “Ok alright, you're comfortable now”.

Let's talk about your friendship with Carlton. Because you've been working together since the early sound system days through the years and you still record together.

Yeah man, it's a team. Team work you know? He's my brother (laughs), so long entwined and we know each other good. He can go there and talk to me and so it goes.

In the last decade you’ve been working with European producers like Tandaro, Grant Phabao and Bost & Bim (for whom you did a cover of Estelle’s American Boy)?

Yeah, yeah, yeah, sadly Bim died. He passed on. That was a good tune, yes. American Boy - Jamaican Boy (laughs). Well Tandaro is Helmut from Germany and Christian Frank. They have some new style of rhythm that they make. Just like how they make in Paris with Grant Phabao, TIMEC Records and Djouls. Same thing with Helmut and Christian, new flavours, new ideas. We’re doing some things and it's working and it's good.

Tell me how it feels to be doing a lot of work with the younger generation of people in Europe and around the world?

Well they understand my work, you know? Because me and a lot of them work and even the language barrier is no problem. They listen to the rhythm, they know the beat. They know reggae music is a heartbeat, the drum and bass heartbeat, so if you have the timing on the beat you can do anything on reggae music. It's an international music.

Do you ever get nervous before you perform?

One time. No, well, (laughs) what I know about this music business is no matter how big you are in the business, how powerful you are, there's always a little bit of butterflies. When you're about to enter the stage and they say “Ladies and gentlemen…” and you go “Christ!” “People are you ready…” and you go “Shit, oh no…” “Get ready…” “I going to start this now?” It's that. And when they call you and you have no choice but to go on stage that's when everything changes and everything transforms! Because you're on stage and you better do what you're doing now! Because you're as good as your last performance! (laughs) It's helpful. That little butterfly is good because once you start and you start strong then it all goes away.

Final question... you said at the beginning you don't like interviews - why not? You seem fine in this one?

Yeah well you have to dig because there are so many missing parts! (laughs) Too private. Too private. I mean the top part is ok to talk about but when you go deep into it people try to find out certain things that you left in the past.