Linval Thompson ADD

Interview - Linval Thompson Still Moving Strong

09/30/2019 by Rafael Konert & by Angus Taylor

Few artists have embodied reggae music’s fundamentals like singer and producer Linval Thompson. His mellow, mellifluous, almost mocking voice, set to heavy drum-and-bass, created a vibe that stands out among many of his more traditional song-crafting peers. His productions, usually recorded at Channel One studio using the Roots Radics band, are quite simply the finest examples of late 70s/early 80s roots reggae and proto-dancehall ever assembled.

His music aside, Linval Thompson is far from your typical Jamaican artist. Where lots of his contemporaries are big talkers, Linval is a soft-spoken man who has kept fairly quiet about his accomplishments. Despite producing only sporadically since the 1980s he has continued to earn a living licensing his considerable catalogue. His live shows are exemplary in their standards: his voice unchanged and his choice of band always top notch and rehearsed to perfection.

Angus Taylor and Rafal Konert joined forces to interview Linval before a triumphant performance at Rototom Sunsplash in Spain - backed by Roberto Sanchez and the Strong Like Sampson band. It took their combined efforts to get the never overly talkative Mr. Thompson to open up about his life and career. He shared some hitherto less known details from his early days in Jamaica, New York and London, staked his claim as auteur of his amazing productions, and announced that some forthcoming new music with Roberto Sanchez and Luciano is on the horizon…

You're the only person in your family who made music. What did your parents do for a living? What was the family business?

No, nobody, no. They used to own a mini supermarket. In New York they did domestic work, like a nurse's aide and things like that.

What kind of music were you exposed to as a youth?

You had the ska. Like the Derrick Morgan, the Prince Buster, Delroy Wilson, Alton Ellis, John Holt and Dennis Brown.

How did you discover you had a voice and get interested in singing?

Well, I never said this before but when I was a youth, I used to keep dances. Like sound system, big sound and from there I kind of got into the music. I never said that before.

Which sound was it?

The sound was named Sir Percy. The sound came from in the downtown area. I kept that dance in my mother and father's place in Crescent Road, Kingston 13 area. First time I said that.

Where did you start singing? Because you didn't sing in church or in school competitions…

The only time I would sing was in my yard. In the yard I’d sing but that wasn't really singing. I never really went to any place to sing then. Nothing like that.

You moved to New York City with your parents because your parents wanted to take you away from dangerous influences. How did Jamaica compare with New York?

Well it was different. Because when I went there in Queens I started to make friends with Jamaicans, one or two or three or four. And when I remembered my friends that left me before for Jamaica to New York, I tried to find them. So it wasn't violence like Jamaica at that time. Because in Jamaica you remember you had the political two sides that were going on before my time and it still was going on. So it was a problem. And I wasn't thinking about music as a professional to do anything. I was just thinking to follow my friends doing different things that were not right.

Johnny Clarke was a good friend of yours when you were growing up. Did he spend time with you in New York and did he encourage you in your singing?

Johnny Clarke, yes, he was my friend from the same neighbourhood where we came from. He came out to New York because he was touring so he would always come to where I would stay. We never really talked about singing. He would just come to do his show but I don't remember him encouraging me like that.

You recorded your first tune No Other Woman in New York City. Can you tell me a bit more about how you got to the studio and how it came about?

Well I never knew about where to find a studio. The same thing in Jamaica. I’ll tell you this. I never said this before because things are just coming back… Jacob Miller, we used to go to the same school. He said he was recording. I heard that he was recording songs so I asked him take me to the studio. It never happened but I heard that he went to… I think it's Coxsone…

Yes, he went to Coxsone. He was meant to record on the riddim to Nanny Goat but Coxsone didn't release it…

Right. And I said “I want to go, take me there, man” but it never happened. I never said that before, never, but that was the first time. We used to go to Melrose School, that's long before going to America, with Jacob Miller. Johnny Clarke, I think he was singing but he wasn't a hit yet. But me and Jacob Miller were more like that because we went to the same school. Me and Johnny Clarke never went to the same school. It's through singing that I linked with Johnny Clarke. But it never happened. We never went to studio until when I went to America. My friend named Patrick Alley, you must know Patrick Alley, check to know a song that he sang. I'm trying to find him right now I can't find him. I don't know if he is around still but he is the first man who took me to Brooklyn and said “Here is the studio”. I don't know if I remember the name… Art Craft? It was a white man studio and it was a nice official studio. It wasn't like something like Tubby’s or Channel One. It was those big-time studios. And he introduced me to some musicians. The name was Buccaneers but I can't remember who were the players, who played the bass, who played the drums, I don't remember that. But I remember that Bunny Rugs was around there. No Third World.

Before Inner Circle or Third World.

I met him before he died and we talked about that. I said “Remember me man” and he said we could even do some production but we never made it work.

He was a nice person.

Yes man. He was always smiling.

I think we should talk about your first recordings in Jamaica…

The first one was for Keith Hudson and Stamma. Stamma was Keith Hudson's good friend. He had the tapes for Keith Hudson and he heard my first song that I recorded in New York and I brought. I also pressed the song too. That's the way I did it and people started to hear the song and say that I sounded good. So that's the way I got confident now and said “Yes”. But when these producers heard me I never knew that they were big producers because I wasn't in the business to know who was big and who was not big. And they said “Yes, we're going to take you to the studio”. I said “Yes, no problem, I'm ready”.

The song Westbound Plane was recorded in Randy’s Studio. How were Randy's vibes? Randy's was one of the favourite studios back in those times…

Yes. For special artists, not for every artist. I went there with Bunny Lee but I don't remember if that first song it was there we did it? Maybe it was there that we did the Stamma song. It had a good sound man. Big sound, professional thing in that time.

In the Rototom Reggae University you spoke with David Katz about recording Kung Fu Man for Lee Perry at the Black Ark Studio. You said Lee Perry came up with the Kung Fu lyrics. Lee Perry had a reputation for dancing in the studio, so was he acting out the Kung Fu moves?

He was making a move like “Huh! Ha!” Yes, because he got excited! We did two songs but I don't remember the name. I think it was something like “Girl you've got to run, you've got to run” something like that. But I know we did two.

Where did you learn production skills?

I would say at King Tubbys. Right there. I had been there with Bunny Lee. We would sleep there. We would wake up there. Then after I started to do my thing with King Tubbys, do the production, so it's got to be right there.

You were recording Rasta lyrics from early. How did Rasta come into your life?

Well I'll tell you the truth, the Rasta it just happened. Like a miracle. Because I saw what's going on around me, many Rasta in the '70s, Rasta all over Jamaica. I saw that and that gave me a vibes and it just happened to me. That vibes.

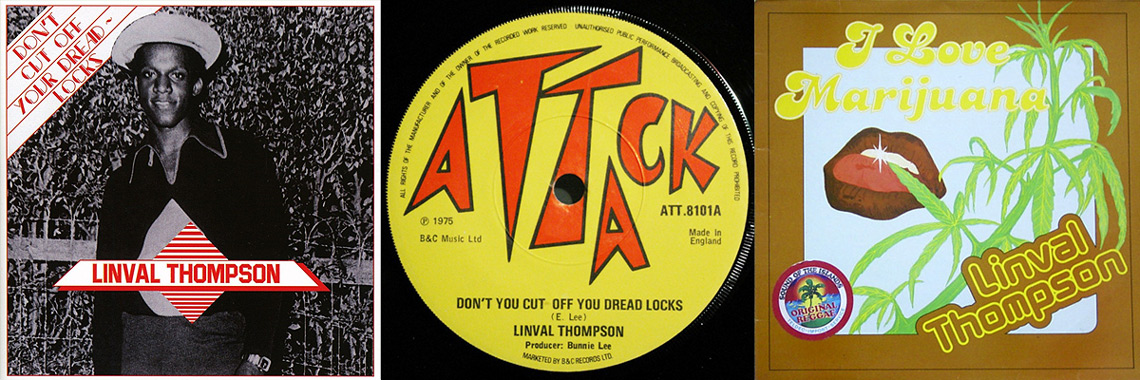

For Bunny Lee you recorded Don't Cut Off Your Dreadlocks and Long Long Dreadlocks. Later your label name was Strong Like Sampson. Was the story of Sampson significant?

You know, it was in the dance. When they would play a Linval Thompson, the selector, guys like I think maybe U-Roy, right in that time, they would say “Linval Thompson, strong like Sampson” and that's the way it happened.

At the time that you sang Don’t Cut Off Your Dreadlocks were the police still trimming Rasta?

Yes man, I think so. Yes, the police never liked Rasta at that time. Everybody was against Rasta. That's why when I sang that song it exploded. London was the same problem. Hit! The whole of London was Rasta and nobody was singing for Rasta. Remember it was pure Lovers Rock singing in London. I never forgot when I started to sing roots songs, the guys on the radio started to talk and write in the paper “Linval Thompson only sings about Rasta”. I never forgot until I had to change the style and start singing Lovers Rock. Yeah that's why I started to sing Lovers Rock in London. I never forgot that talk.

Your second album I Love Marijuana was your self-produced album. Which studios did you record that album in? Was anyone helping you, like an engineer?

No nobody. I rented Channel One and I made the tracks. Then I went to Tubby’s and I rented Tubby’s. Many times, I couldn't pay Tubby's and I had to leave my tapes and said I would come back and pay. So when I left the tapes, Tubbs would use the tapes and sold specials. We didn't call it dubs. We called it specials at that time. And the people who came from the country he would play the tracks and say “You want a special off of this?” And they would say “Yes”. And “Now we're going to know whose song is a big song”. One more thing. Did you know I was the first man to sing a special? Well I want to prove it. Did you know I sang the first song for Tubby's – Whip Them King Tubby’s? I just released it a couple of years ago. That was a Tubby track. I voiced it for Tubby's. Tubby's just played it for the sound. Whip Them King Tubby’s. Check it out and find it out for yourself.

As well as your career as a singer you also started producing different artists. Did your skills behind the microphone help you to become a good producer?

Yes, because when I listen to an artist, I know what I want. Because I see what the public is interested in. That's the first move. And I see what’s going on in the ghetto. So I try to do what is going on with the youths. Some people just make music because… but I don't just make it like that. I have to see the vibes and listen to the sound. The style and the lyrics and listen to truths and rights. I don't write something but don't mean it. That's just in me.

Let's talk about your experiences with Trojan Records as a distributor. You spent some time living in England for a while.

Well when I came to Trojan you had those big artists like Ken Boothe there. Some big-time producers and big-time singers were there. So I came as a little youth because they didn't hear about me with Don't Cut Off Your Dreadlocks. So when I came with I Love To Smoke Marijuana and a dub album named Negrea Love Dub and a Big Joe album named African Princess, those were the first three albums I made. I never had enough money but I used the tracks if you understand me? And you’ll never know this, but Gregory Isaacs was the first man who gave me a couple of rhythms. If you listen to that dub album, enough of those tracks are Gregory tracks. When he gave me those tracks, I voiced on the tracks at Tubby’s and then I made a dub out of it.

So they are African Museum rhythms?

Right. But enough people don't know that. That's the first time I said that.

Let's go back to the Channel One days. At Channel One there were two bands: the Revolutionaries and then the Roots Radics came in the '80s. You worked with both of them. What was the difference between them and which did you prefer?

I started to work with Sly and Robbie first. But when I started to work with the Roots Radics I just tried to have a different flavour, a different sound. And I noticed that the public really loved the Roots Radics’ style. So I kind of stayed with the Roots Radics. But Sly and Robbie had a different style. It was like for different kind of people. But my style was for people that dealt with the roots. Remember we were in England and they love that style. Because in England we used to base. You talked about dub.

As a producer how would you define dub?

Well when I came with the dub style it was exciting. Because Scientist says that it was him that made it happen. How could Scientist make it happen? And he never produced one tune. You tell me. How could Scientist make it happen? When we went to Tubby's, Tubby's was the first man who mixed I Love To Smoke Marijuana in dub style. Scientist wasn't there. Where was Scientist? So I saw what Tubby’s did and I listened and I said “Yes, we want the same sound”. So when Scientist came long after we told him we wanted that style. We wanted that sound. Scientist never came to England. Scientist didn't know what the English people want. I went to England and saw what they want. With that big “Bo!” “Slam!” “Bo!”. And then we made it happen. Scientist says it's him that made it happen. He was working for Tubbs so we did need an engineer, right? We needed an engineer and Tubbs had him as an engineer. He says a different thing.

In a 2013 interview for United Reggae, Al Campbell said that he was the one behind your productions. He had the golden touch that made them hits.

(laughs) Okay, well you see everybody tries to say. So if he was the one why wasn't he doing things for himself to make it happen then? Answer me! (laughs) Was he there when I was making Don't Cut Off Your Dreadlocks? Ask him that. Was he there when I was making I Love To Smoke Marijuana? Was he there? I was hitting myself before I started to produce different artists. Am I wrong or right? Big Ship Sailing On The Ocean came long after when Freddie McGregor came to my house and he looked and he saw the ship. If I never had my house at that time the guys would say it's their money buy my house! If you understand? So I always say it. I sing and I make it happen and I had everything before I started to produce. If you check back the record. I hired them. They never hired me. But you see everybody is looking for a big fame now. That's the problem. But that's no problem to me. I'm still making songs and it’s still working. Me and Roberto Sanchez are working on a big project. New songs. New everything.

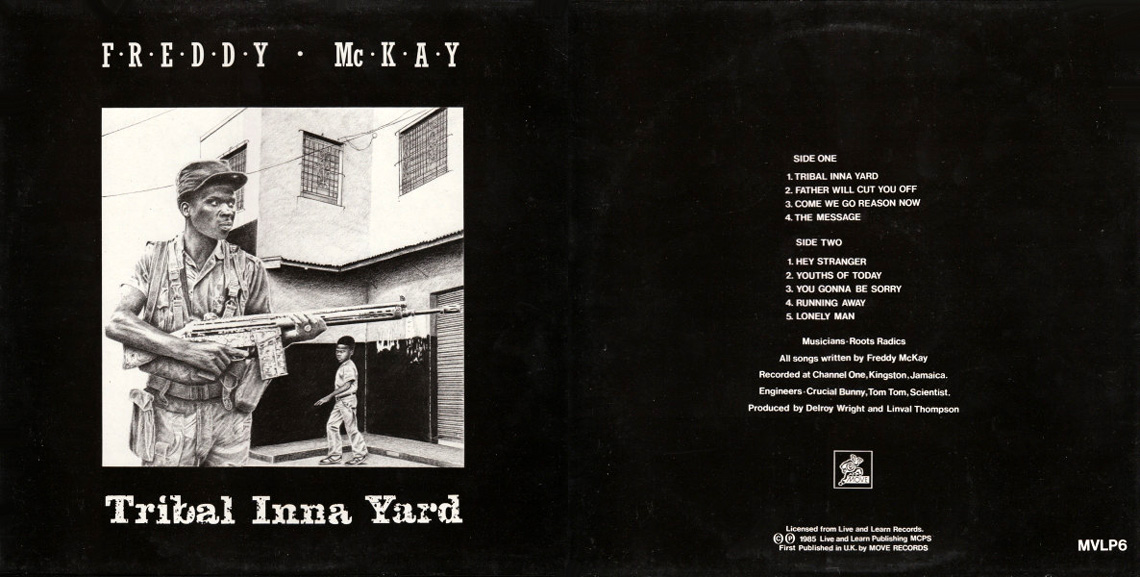

You recorded the last great album by Freddie McKay, Tribal Inna Yard released in 1984. He passed away in 1986. What kind of person was he?

Well I just knew that he could sing. I never really knew him for a long, long time. But just because I was making songs at Channel One, you know when a guy comes he wants money, so I tried to find the money. So that's like they are ready to sing. Because without money those guys are not going to sing. That was the vibes there really.

Tell us more about this new project with Roberto Sanchez.

LINVAL: Well as I was saying, some of these guys that used to be alongside with me like Al Campbell were saying that he was the one making things happen. I'm producing songs still. I never stopped. I'm working. Me and Roberto Sanchez are working now. And you’re going to see. We're going to have hits. It is there right now. You're going to see. Hot hit right? I come with my ideas, Roberto Sanchez he has his ideas and we’ll make it work.

ROBERTO: You know it's just amazing having someone like Linval back in the business with such a great catalogue and such a great sense for producing good music. He has a special skill for recognising good songs, good artists and he had it from the beginning. He is back. He just needed an engineer. To mix his stuff, to push his quality and his skills. He's voicing new artists, and back-in-the-day artists on his old-time rhythms from Channel One and massive things are going to come now. That's all I can say.

LINVAL: So we're going to see all these guys who say that they make things happen. When I come with this Luciano, this brand new Luciano album and some singles, you tell me if they are the ones who make it happen. And we have these new girls, female artists coming - you tell me if it was those guys who make it happen. I want you to find them and say “Linval Thompson is moving strong”.