Linton Kwesi Johnson ADD

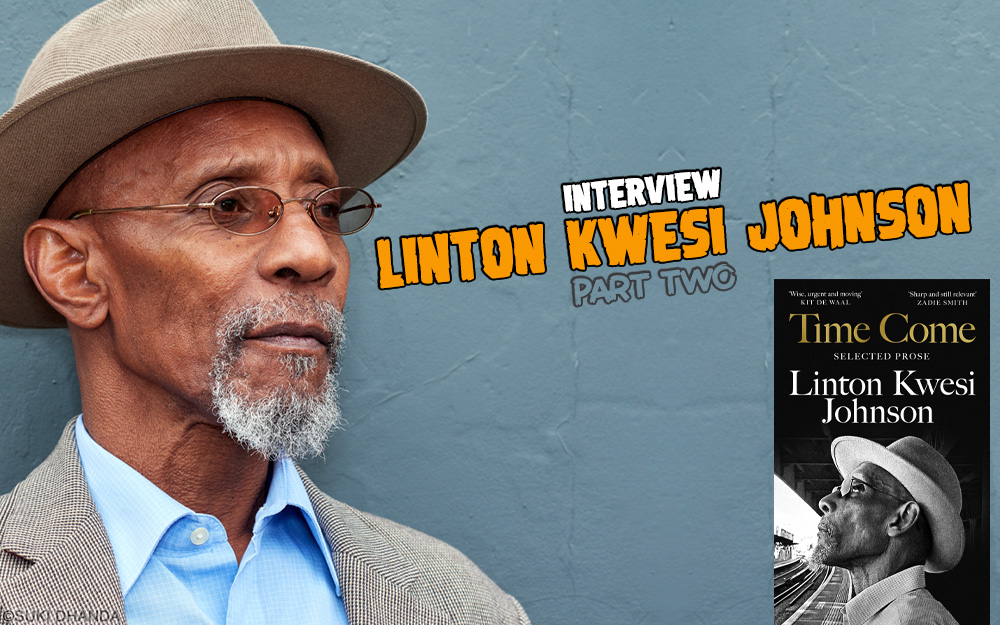

Linton Kwesi Johnson | Interview Part II

09/11/2024 by Tomaz Jardim

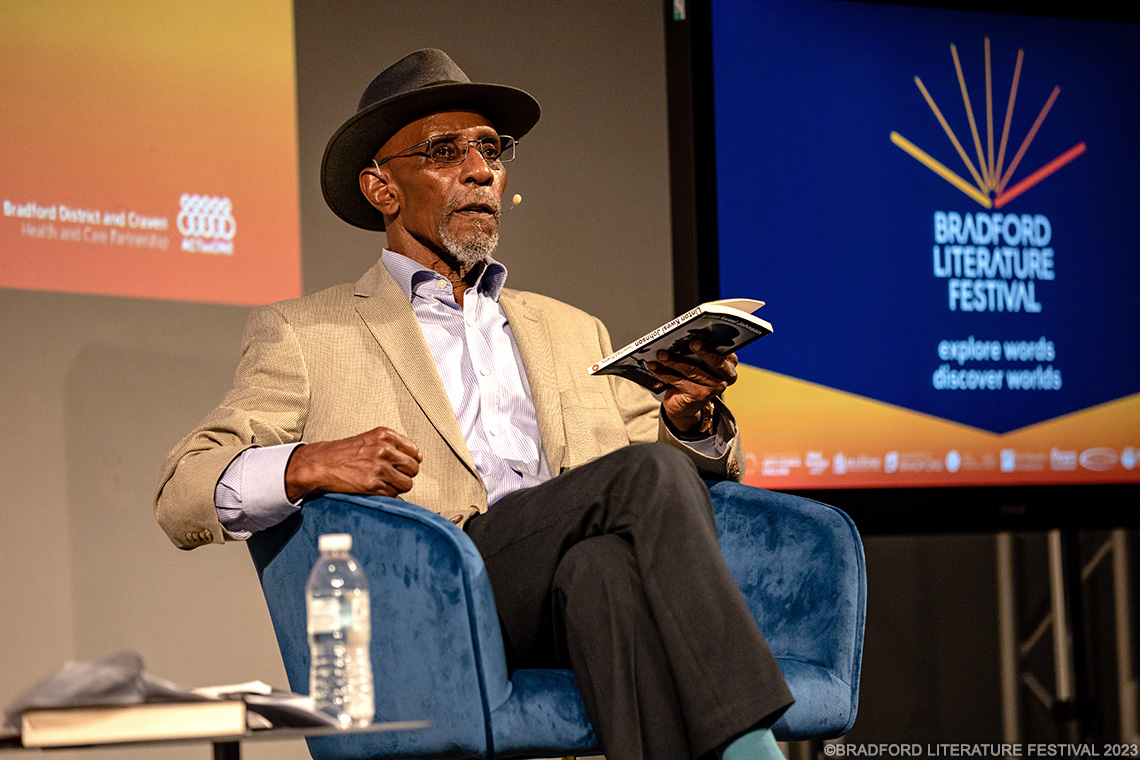

In this second part of my interview [read PART I here] with dub poet and author Linton Kwesi Johnson, he reflects on the evolution, impact, and political dimensions of reggae music.

You arrived in England in 1963 as a relatively young boy, really at the moment when Jamaica was embarking on a remarkable few decades of unparalleled musical creativity and output. In writing so much about reggae as it was emerging with such force, I wonder if you can account for that explosion of creativity in Jamaica - why then and why there?

I don't know if I have the answers to that [laughs]! It seems to me that there'd be a lot of different factors that contributed to that. Jamaican people are very creative. There's a whole heap of talented people in Jamaica and very strong folk traditions rooted in some African influences and a lot of other external influences. Jamaicans used to listen to American stations before we had our own radio stations. We used to pick up stations broadcasting out of New Orleans or places like that. So we were hearing American music and even though Jamaica is a little tiny island in the Caribbean, it was part of the modern world. And some of our musicians were schooled in Western traditions. Alpha Boys School, for example, played a crucial role in the birth of Jamaican popular music, because that’s where a lot of our horn players got formal training, where they’d be playing classics, marches, film themes, and so on. So there were diverse influences - the influences from our African roots, the local Jamaican folk tradition, the European influences in the folk… I mean if you to listen to a lot of Jamaican folk songs, you can hear a lot of Scottish and Irish influences, like the Scottish reel, the Irish jig and so on. Then there’s the African-American music which came out of the plantation experience, which parallels the Jamaican plantation experience… It’s all very complex. It’s a unique melting pot out of which this sound came.

Well, they say “out of many, one people,” maybe it’s also “out of many sounds, one sound!”

Absolutely! I mean, it was a great big melting pot, with a lot of diverse influences which uniquely produced this sound.

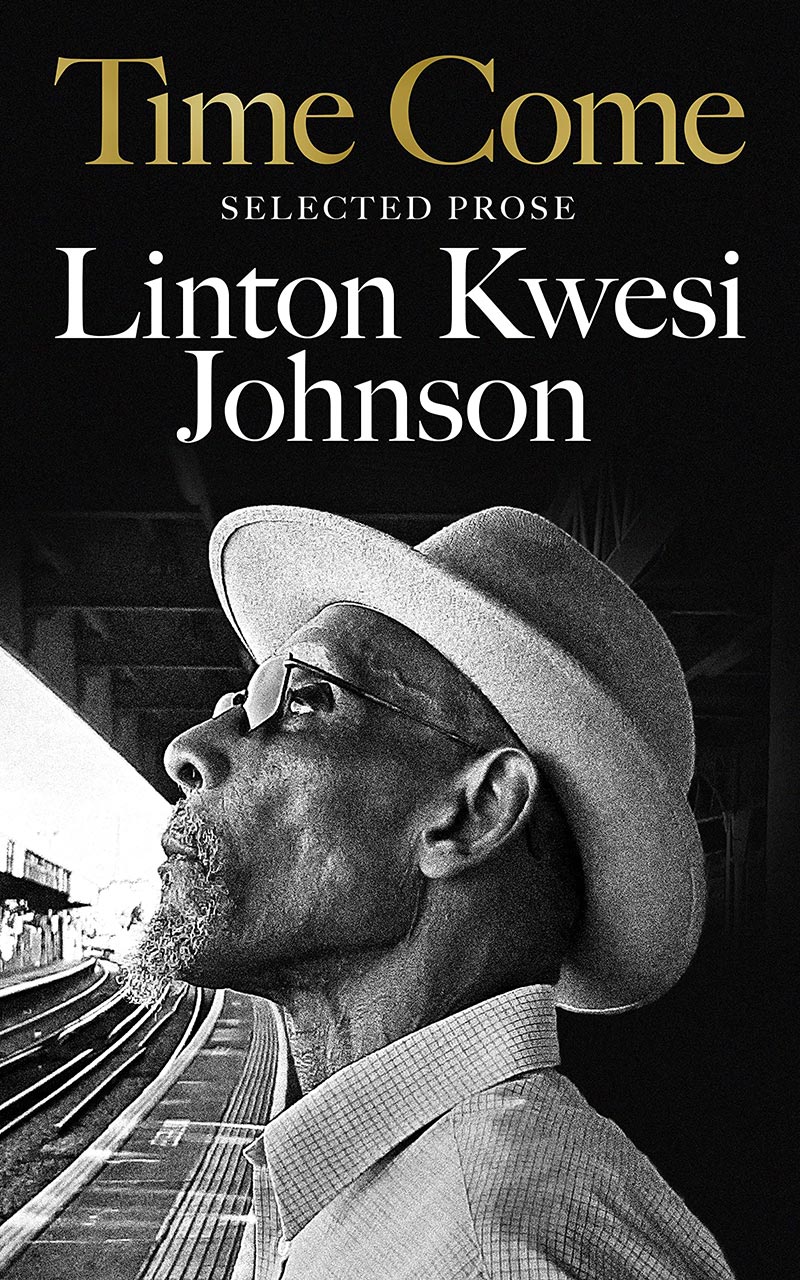

In your writings on reggae in your wonderful new book Time Come, I get the impression that you saw yourself as a bit of an observer and a cultural critic looking in, rather than always as a part of the scene you were describing. Was that just the voice that you adopted for your writing or does that in some way reflect how you felt at the time?

You may be onto something there actually, because from a sociological point of view I guess you could probably call it ‘sympathetic introspection.’ I mean, I was always a great student of the music from when I was a kid, because I was learning so much about myself coming here at eleven. I'd been already socialized in the Jamaican folk culture and so on, but there were things I didn't know, and I was learning about my own culture and my own roots from the music. So I wasn't just simply a reggae enthusiast. I was a serious student of reggae and I wanted to write about it with the same approach to it as a literary critic would to literature. So I guess stuff that I wrote is a result of those elements.

You write about Rastafari within the book with admiration, especially for its anti-colonial ethos, but it's not a movement that you joined. I wonder if you could say anything about how you saw the role of Rastafari in the 70s and how it intersected with, but also diverged from, your own outlook?

Well, Rasta is crucial to the development of reggae music, both musically in terms of the Nyabinghi drumming, and the anti-colonial sentiments which gave reggae music a unique ethos. I don't think you'd find any other popular music in the 20th century that was secular and yet with that level of deep spirituality. It armed reggae culture with a kind of a uniqueness in terms of dreadlocks, and the red, golden and green. And people began to remember, or even to discover, the ideas and the teachings of Marcus Garvey and the basis of anti-colonial resistance and anti-colonial sentiments. Rasta was crucial.

But it didn't strike a chord with you personally?

No, I grew up in the church like most Jamaican peasant boys from peasant families. Jamaicans are very religious people. And once I became politically conscious, I was leaning more towards atheism or agnosticism, and although I could identify with Rastafari and found it alluring, I couldn't bring myself round to the notion or feel comfortable with the idea that this man Haile Selassie was god. I also didn’t think that repatriation to Africa as a whole-scale movement was something that was viable. I mean if people wanted to go back to Africa or go to Africa, then that was fine by me, but what was more urgent was gaining political, civil and political rights and freedoms, and to challenge the oppressive environments in which we live, and to fight for power - for black power, for people’s power, for working class power. So I became a political animal and more or less abandoned any idea of the Christian ethos - - that you're dying and you're going to heaven in Jesus name, as Bob Marley says in one of his songs. I mean, I grew up taking all that for granted and then I broke with that completely. Once I discovered the part that Christianity and Islam played in the enslavement and oppression of black people, I rejected all religion. I was never hostile to religion, because I think it is futile to be hostile to religion because I think religion is something which is part of our human dimension, it’s part of what makes us human - this need for a belief in something… I mean put it this way, there will always be god because god is the answer to all the questions that science can't answer.

You mentioned Bob Marley just now. I found some of the portions of your book specifically addressing Bob Marley particularly interesting, given you were writing from the perspective of the mid-1970s…

Back in those days, I was the only one who ever wrote anything critical about Bob!

Right! I wonder, however, if looking back fifty years later, you are any more forgiving in your assessments? For instance, you talk about the “unfortunate evolution” of the music of Bob Marley towards what you call “contrivance and vulgar eclecticism.” Do you still see it that way?

No, I don't see it that way. I tell you what: I was a reggae purist one hundred percent. And I wanted the music to be accepted on its own terms. And I was pissed off by the idea that Chris Blackwell and other people in the business were trying to make it more palatable to a European or non-Jamaican listener or audience. Like in the early days, they’d put a lot of strings and stuff with John Holt to appeal to the British Housewives, because he was singing nice, romantic love songs. But it was hard roots Jamaican reggae in the background. So it was kind of a diluting down for me, of the real authentic roots stuff. I was a reggae purist, and a self-righteous one at that. And of course, later on, I began to understand that Bob and The Wailers had incorporated a lot of American influences. They were inspired by groups like The Temptations and R&B music coming out of America. And they wanted to cross over and reach out to an international audience. So it wasn't alien to bring in rock and blues and other elements into their music. These were elements that they'd already been influenced by. My own outlook was significantly changed once I began to make records myself. You're in a studio making a record and you've laid down your rhythm tracks and you think to yourself, well, there's a break there where nothing's happening. What would sound good there? Would a violin sound good there? Would the accordion sound good there? And then I began to see it differently, you know? But back in those days, I felt that this is our music, accept it on our own terms, rather than trying to muck about with it. But of course Chris Blackwell was a genius in the way that he made Bob's music more accessible to a global or international audience.

As I'm sure you're aware, there's the new biopic film Bob Marley: One Love out there. Have you seen it by any chance?

Yeah, I've seen it. I was a little bit underwhelmed by it. But I think for a younger generation of listeners who probably have just discovered Bob Marley, it will give them some kind of an ‘in.’ They'll learn something about the man and his music, even though it only covers two years of his life properly. But I found it a little bit underwhelming. I was so pleased, however, that the two Black British actors who played Bob and his wife, Rita, got the accents right anyway.

The opening chapter of your book quotes your own song, Bass Culture, to refer to reggae as “music of the blood, black reared, pain rooted, heart geared.” You also write that the music “beats heavily against the walls of Babylon,” and that “Jamaican music embodies the historical experience of the Jamaican masses.” Would you still use this language to describe the music of Jamaica today? And if not, when did the music stop warranting that label?

By the eighties, the music stopped warranting that label, with the advent of the dancehall phenomenon. I mean, early dancehall, I loved early dancehall! You could dance to it. And there were some great lyrics, some very witty stuff that made you laugh and there was still an element of protest or social commentary. But then it sort of degenerated into purely libidinous sexual stuff - people talking about how big their cocks were and how many women that they'd had and denigrating women and so on. That coincided with the end of the period of democratic socialism in Jamaica, and the new tenure of the Jamaica Labour Party. I don't know how these things work out. I haven't really thought about it deep enough, but that was a period of Reaganomics and Thatcherism, when economies were being restructured and the state was being shrunk however modestly at the time. But there seems to me to have been a whole shift away from the spirituality that was represented by Rastafari within the music, and a move more towards materialism, and the consumerist ethos took over from the message of peace and love and black liberation.

You also write about the decline of reggae as a soundtrack for this generation of Black British youth. I'm curious if you see any of the cultural vacuum that this has presumably created being filled with other art forms?

Well, it's one generation growing up and becoming adults and another generation emerging. So that music ended with one generation, and with a particular phase of our struggles for racial equality and social justice in this country, and the end of a particular phase in terms of our struggles to break down the colour bar and so on. If you look at Britain today, it's a different place completely from when I was writing all that stuff. I mean, we've been successful in integrating ourselves into British society and breaking down a lot of those barriers, so that the generation that came after didn't have to fight those battles. The things we had to go through weren't the next generation's preoccupations. But there's been a continuity in terms of different genres. Coming out of dub for instance, you had the drum and bass, you had jungle, you had dubstep, and even the grime music, which is the music of the black youth of today. So there's still that continuity, that link with reggae, the spoken word, and the rhythm, and the drum and bass track, and so on. So there's been change, but there's been continuity. What I find interesting is that even though the influence can be traced back to reggae, the grime music is mostly the product of the youth of second generation West Africans: Nigerians, Ghanaians and so on. It's their time now to make an impact on British popular culture in the same way that my generation did back in the days of reggae, and it’s something new and something that sounds completely separate from the reggae tradition, but if you examine it from a historical or musical perspective, you can find that there is a continuity that can be traced back to reggae and sound systems and all of that.

You have described how your generation transformed British society through activism and insurrection, and that it was reggae that helped to propel that generation in its fight for social justice. Looking back fifty years later, would you say that reggae fulfilled the promise that you so clearly felt it had when you were writing in the 1970s?

Yeah, I think it did the job. I don't want to use too big a word, but it was ‘phenomenal.’ Phenomenal. I guess it was as important for that generation as protest music was in the Sixties, for the generation of the Vietnam War in America. Protest music played a big part in American politics back in the day.

Before we wrap up, I am always interested to know what the records are that have been seminal in the lives of influential musicians like yourself. Are there records that you played fifty years ago that you still pick up and play today? Do you still listen to a lot of music?

Not as much as I used to. I read more. God, it’s difficult, because stuff that I listen to now that I was listening to when I was young would be like Miles Davis and John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk. In terms of Jamaican music, it would be The Skatalites and instrumentals; I still love Burning Spear. Bob Marley and the Wailers music I still listen to - it still sounds so fresh, so contemporaneous, as if it were made just last week! I still like to listen to Toots and the Heptones. A lot of the time when I'm playing old Jamaican music it’s the Rocksteady stuff because that's the music of my youth when I was a teenager. You get nostalgic when you’re an old man like me! You put on that old music. But I still love all the reggae greats: I love Ken Boothe, Delroy Wilson, all these people. But if I want to relax and chill out, I might put on Straight, No Chaser by Thelonious Monk or something like that. I even listen to a bit of classical music from time to time, on the radio. The station I listen to mostly is Jazz FM.

Finally, I've heard you say that you seldom write poetry anymore. What about future musical performance and recording? Is that also behind you or might we have the opportunity to see you in the future?

Well, never say never! I keep getting invitations. People want to bring me out of retirement, offering me ridiculous sums of money! And I'm thinking to myself, why didn't you offer me these monies when I was active, instead of now when I’m an old cripple and can't stand on the stage for two hours anymore because I've got arthritis! But I got a little bit tired of the adrenaline hit that you get performing, because it takes you too long to recover from. You know, you go and do a gig and everything goes right, and it's a kind of high that nothing can be a substitute for - not cocaine nor ganja nor anything else. It lasts for days and days, and it takes you so long to come back down to earth, it's too traumatic, man! But never say no. I still do poetry readings. And people keep offering me ridiculous sums of money to go back on the road, but I don't know. Let's see how the pension goes!

Okay, I'm glad to hear it's not a no!

The interview appeared first in the FESTIVILLE 2024 magazine. Click here to download it as free PDF!