Kiddus I ADD

Interview with Kiddus I

03/09/2013 by Angus Taylor

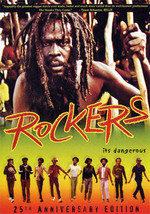

In a follow-up of sorts to our two part interview with Fred Locks [READ IT HERE], Reggaeville got the chance to chat with another veteran Rastafarian singer known for a striking unusual voice and a quality-over-quantity back catalogue. Frank Dowding, dubbed Kiddus I (“Blessed one” in Amharic) began recording in the early 70s as a solo artist and as a member of Ras Michael’s Sons of Negus. But his big moment came via an iconic scene in Ted Bafakolous’ 1978 film Rockers, when main character Leroy Horsemouth Wallace arrives at a Jack Ruby session to see Kiddus singing the hypnotic Graduation in Zion. Like Fred Locks, Dowding never stopped laying tracks after the late 70s - in JA, the US and the UK - yet somehow many results were lost or failed to see release.

A couple of compilations from rescued tapes aside, Kiddus did not put out an album until 2005, when he voiced for the French label Makasound with Earl Chinna Smith’s acoustic collective Inna De Yard. This gave rise to 2009’s Green Fa Life: the musical mouthpiece to an eco-friendly agriculture programme he has been running in Jamaica. An appearance at France’s Reggae Sun Ska festival with Sebastian Sturm’s band Jin Jin resulted in his third album Topsy Turvy World. Issued in February 2013 it attempts to right the missed opportunities of the past - by creating vintage 1970s roots rhythms using Jin Jin and old friends like Familyman Barrett, Chinna and Sticky Thompson.

It’s fairly clear when talking to Kiddus I that he is more bemused than embittered by his less than prolific output and the lack of royalties from his cameo in Rockers. But then, he takes the view that music has always been a vehicle to further a variety of good works: from his 70s involvement in the Café D’Artique arts and crafts commune or the Peace Movement to stop political violence to Green Fa Life today. Reggae historians may be interested to hear below that Kiddus was one of the last people to see the equally under-recorded Jamaican poet Michael Smith alive. They can also listen to a phoneline recording of an original poem he recited to Smith on that fateful day in August 1983 (apologies for the quality of the sound being quite poor).

It’s fairly clear when talking to Kiddus I that he is more bemused than embittered by his less than prolific output and the lack of royalties from his cameo in Rockers. But then, he takes the view that music has always been a vehicle to further a variety of good works: from his 70s involvement in the Café D’Artique arts and crafts commune or the Peace Movement to stop political violence to Green Fa Life today. Reggae historians may be interested to hear below that Kiddus was one of the last people to see the equally under-recorded Jamaican poet Michael Smith alive. They can also listen to a phoneline recording of an original poem he recited to Smith on that fateful day in August 1983 (apologies for the quality of the sound being quite poor).

Unusually for a Jamaican youth, you went to a Quaker School - Happy Grove High.

(laughs) I got a scholarship for the school back in 1959-60. I think it was one of the only Quaker schools in Jamaica at the time – there was also one in Highgate. It was not much different to other schools but I did get to do the history of the ancient Sumerians – not many schools at the time had that text. In church there was a period of silent meditation. We went to church every morning. I was in the choir. In a sense it was a co-ed school with boys and girls – and I had a good time!

Did you have friends’ meetings where you sat quietly and if something came into your mind you were allowed to speak?

Yes, if anyone had anything to say you could get up and give a testimony and speak on whatever subject. This was given every day – if someone wanted to express themselves they had that freedom. If you came up with an idea or questioned something you were able to ask it, whatever it was. Sometimes people would try to answer your questions, or if you had a suggestion it would be taken or not – but you were free to enter into whatever you wanted to question.

You mentioned being in the choir. How did you first become interested in music?

That was like breathing I suppose. I was singing a song from the moment I was able to sing. My father had a lot of music – both my mum and my dad sang so we grew up in that environment of expression. By four years old I was singing – and actually getting bribes to sing! So you could say that at four-five-six I was being paid to sing. If I was singing freely then it was ok – everybody could hear. But if I was being put on the spot by someone saying “Oh he’s got a nice voice” and taking me out of my mode I wouldn’t sing like that just so – so they would bribe me! (laughs) After they put money up and if I felt like singing I would sing in front of them – or I would go in a room away from them and sing from inside to myself where they could hear me. Singing was like second nature to me.

You would later run the Café D’Artique commune for many years. How did you become interested in arts and crafts?

I did art in school and I was quite good at drawing. In fact I got 100 out of 100 for an art piece that I did. They said you couldn’t get 100 in art but this American headmaster who was an art teacher gave me 100. So I did have skills at it – I never took it commercially but as a musician and an artistic person I did the arts and crafts like tie dye, batik and leatherwork and a variety of other stuff. I did painting for a while. It was all just a true and natural expression we identified with.

Like many enterprising young kids in the 60s you carved your own instruments.

In High School we would make bamboo fifes and some of our own instruments. Things that weren’t available. Then I tried out the trumpet but I didn’t like the way it made my lip feel after a while, so I gave it away. Later I played drums as a member of Ras Michael and the Sons of Negus for maybe seven years and then I played drums in Inna De Yard.

How did you come to Kingston?

From a little boy my family moved between Kingston and the country. When I left high school I came and lived in Kingston full time, doing diesel mechanics or diesel engineering as an apprentice, and then after a while I went into surveying for real estate. Since 1969 when I left the bauxite industry where I was doing surveying, I have been self-employed and the music has been one of the main sources. But at the same time I did arts and crafts – silk screen printing of t-shirts – and a variety of other things. I did some farming at times.

Ras Michael and Aston Familyman Barrett were very important in your early days in music. Which did you link first?

Familyman actually played piano on one of the first recordings I did. Carlie, his brother, played drums, Sangie Davis played guitar and actually Bunny Wailer played the bass - I gave him the bassline. It was released in Japan and called Careful How You Jump but I did it in ’72 at 56 Hope Road. I knew Family from the same period but I played with Ras Michael from about ’71 until about ’78, I think, when he left and went over to the States. But we still play now – he’s inside rehearsing and I rehearse with him too. So we are still Sons of Negus in that sense; myself, Chinna and those. When I say Sons of Negus we are Inna De Yard, Rastafarians but at the same time Sons of Negus, the sons of The Almighty in that sense. We all see ourselves as spiritual beings with a certain divine purpose – not for just self but for mankind. We observe and see the ills and the wrongs being perpetrated on the world by our shepherds and our leaders who should be saying “I am my brother’s keeper”.

In 1978 you recorded Security in the Streets with Lee Scratch Perry to celebrate the truce in the political troubles in Kingston and played percussion with Bob Marley at the One Love Peace concert. How did you get involved in the Peace Movement?

Scratch and I were close for many years – some of my earliest recordings were with Scratch. In 1978 during the peace treaty movement myself and Jah Lloyd were at Nyabinghi House – Judah Coptic House of Rastafari – which we started up together in the early ages of our forming as young Rastafarians. We met when he had come back from Canada in about 1971 or thereabouts, when he and I were just turning dread. We became close and he eventually became one of the main spokesmen for the movement. So we were affiliated when Bob came back. I was at 56 Hope Road as a member of the peace treaty committee with the Rastafarian house and Bob and a couple of others. Around that period the UNIA – Marcus Garvey’s movement – were doing a joint thing with the Nyabinghi house. We took over the Heroes Circle in Kingston, this huge park, and every evening from 6 until 9 we had live music – which where live dub poetry really took off. Oku Onuora, Mikey Smith and a number of other artists came and performed. Then afterwards we went into the Nyabinghi groundation and then afterwards in the morning it was the meeting of the UNIA. I was recording with Scratch at that time and he also became involved with what was happening because it was a historic moment in Jamaican history where these two brothers from opposite sides of the political divide had decided enough was enough with this foolishness of shooting and killing our people. The peace treaty came and it was such a wonderful feeling in Jamaica because it resonated a harmonious vibration.

The peace sadly did not last. The election of 1980 was very violent.

At the time I remember telling them that when I was a youth going to Townmore where there was a certain [bicycle] race they called The Devil Take The Highmost. Every lap where you came back up to where you started whoever was at the end drop out and drop out and drop out. So I remember saying to people that the opportunity given to us by the government and the companies and the various media to harness this feeling of harmony – we needed to now put it into positive works in this ghetto area community. Otherwise if we didn’t utilise this moment for the benefit of our people the devil was going to take the highmost. And this is what happened. The progenitors, all of them, were killed off because the establishment didn’t want it. All these people on both sides knew their dirty linen so if you can no longer motivate certain people to do your dirty work this was threatening to their society. So they used various means and they squashed it until we were back at this stage from 79-80 into this tribal political thing.

You mentioned Mikey Smith. He got caught up in all this political violence that lead to his death in 1983 - did you know him well?

Yeah man. I took Mikey Smith on stage for his first dub poetry thing behind live music in ’78. Mikey was a brethren. In the history of it, the night he died, I was going up to visit my children in Stony Hill when driving through Constant Spring I saw him at Manor Park and I picked him up. He had been away for a while and he came back. We were talking and he was filling me in on what was happening because things were going positively in Europe and in Germany and certain places for him. Then I dropped him in Stony Hill – and that was the night he went by a political meeting where he was stoned to death. So I was the last person who knew him who saw him that day. Whoever saw him pass saw him after but I was the person who dropped him off. I even remember telling him “Hey, Mikey, I did poetry too!” and he said “What?” and I started this poem:

SCROLL DOWN TO LISTEN TO THE POEM KIDDUS I RECITED TO MICHAEL SMITH THE DAY HE DIED

Let’s talk about your role in Rockers. You were originally meant to play the lead instead of Leroy Horsemouth Wallace?

Yes, when they first came to Jamaica in 1976. It was myself and a young lady called Fabian Miranda.

She was a poet too.

That’s right. She worked with Jack Ruby, Jack had produced her and I had started doing a co-production with Jack in ’76. That was when [Ted] Bafaloukos came into the studio at Harry J and saw me doing the exact same thing [as depicted in the film] and asked me to keep the song because he wanted to put it in this movie. So it was ’78 when I re-recorded it again live – and actually paid for my studio time and the musicians so I own that three minutes and something that was done on my time. All I’ve got out of it so far is marketing and promotion which I couldn’t have paid for I suppose! But I haven’t got any economic rewards or benefits from it so far. Then Black Disciples went to New York and Bafaloukos met Horsey and Dirty Harry and that movement and decided to go with them. I played my part but no longer was I a possible lead for the movie! (laughs)

You said in the documentary you made about Topsy Turvy World that you had amassed recordings for an album back in the late 70s but the tapes were lost. What happened to them?

I would say I had misfortunes with about ten of my two-inch recorded tapes disappearing somehow. One time I threw away about four of them because I went to a sound exchange studio in LA – a big studio in Malibu. The tapes started shedding a bit and the guy told me they were no good. So I left them in LA only to find out about seven years afterward about the technique of baking! So I lost those. Then I lost a couple down at Inner Circle’s in Florida when they moved. Then at Music Mountain in Stony Hill I left about 12 with Chris Stanley but when I came back I only got five after he died. Then a few tapes got mixed up from my work at Sparkside in London with Matumbi’s Eaton Blake – I recorded quite a bit of work up there. Yeah, I’ve had some misfortunes! (laughs)

Your first released album project was the Inna De Yard acoustic album with Chinna in 2005. How did that come about?

The guys were working with Winston McAnuff and Nicolas [at Makasound] asked after me. Winston told him he sees me all the while down by Chinna so they came down with the idea to record Inna De Yard. At first I thought they wanted to do it in most people’s yards but then the idea just developed into here – Inna De Yard with Chinna and I and I with some other young musicians and the French ones. We did maybe 9 LPs so far and we have another LP which we are putting together to come out later on this year.

How did you come to record your first electric album – Green Fa Life, released in 2009?

Green Fa Life was a vision that I had in Canada – where I was lifted up in the air and was shown water, fresh and salt, and the land to be green. So it’s a commitment to a vision, while recognising the need to be a better husband man in all different ways for the earth, like natural fertilisers instead of chemicals in these pesticides which are so harmful. So I had a track and I had the idea and just made the song in half an hour or so. At the time I was recording it for Inna De Yard because as well as acoustic we also have a variety of productions. So I was using Johnny Moore from Skatalites because he was there with us before he passed, as well as Robbie Lyn and a lot of various top musicians.

Green Fa Life was the musical face of a wider project. Tell us about it.

I have a Green Fa Life programme which is a sustainable development programme for communities where we use moringa as the main plant but also for essential trees and all fruit trees. If we can motivate sustainable development programmes that can feed the basic needs of communities around the equator, the belt of the world, then we can give the people a voice. The beauty of Green Fa Life is that it is like an umbrella in that every culture, sector or class can identify with the need for a green terra firma so we can become husband or husband-woman and become caretakers for Mama Earth and can hand it over to the future generations. So musically we have a platform where we are able to travel and reach across boundaries to promote the Green Fa Life programme.

What is Green Fa Life working on right now?

We want to set up a school feeding programme which is non-profit where they can have stuff with certain nutrients in certain foods that the kids can utilise and the old and infirm can benefit. More or less what I was drawn to as a young man when I heard “One Aim, One Heart, One Destiny” it struck a chord in me and I still see that. Plus it’s food, clothes and shelter - the sick nourished, the aged protected and the infants cared for. And if we work on those six points I think can have a more harmonious coexistence of man and man in terra firma here.

Did you always believe in music as a platform for good causes even when you started recording in the early 70s?

Yes, because you might not want to hear what I am saying, talking in front of you, but the music will play and it will cross the boundaries and come through your windows and you will hear. So music is a fierce medium for expressing positivity or negativity but we see it as a means of enlightenment, untangling some truths, showing some little light here and there. It’s a means that is there for the benefit of upliftment of man. Not something that deviates or runs into a cul-de-sac or dead end. But there are so many seeking minds out there who use music – especially for the youth – so if the message coming out is not positive what you are going to get are headless dolls. But if we use that positively then music can motivate the masses who have minds out there and who are seekers. And for those who are already spiritually connected it is a positive that they can be strengthened by in knowing that there are others who are similarly on the path because there are so many of us around the world who are spiritual and of that network. So we have to control chaos! (laughs)

Your new album Topsy Turvy World grew out of your performance at Reggae Sun Ska with Sebastian Sturm’s band Jin Jin – which I witnessed without knowing its significance. But it also features Jamaican musicians who you’ve known for many years – all making music that sounds like back in the day.

![]() That was where the amalgamation started with Sebastian and Martin from Jin Jin. Then later on I went and did a track with Sebastian and Jin Jin in France for his LP. I did two tracks – I did Wild Child then and I did a rough version of Riddim of Life which I didn’t complete – so then we decided to do this LP. Martin laid a number of rhythms and sent them, I took out most of the bass and used Familyman. I had Tyrone Downie come in, I had Chinna and Sticky Thompson do percussion and I had Bongo too. I have always been close to most of the musicians. Like Familyman – me and him go back 40 years. I’ve worked with Leslie and Harold Butler, I’ve worked with Ibo Cooper, Robbie Lyn, some of the better keyboard players in Jamaica. And as for guitarists I don’t even have to call their names – Chinna Smith, Cat Coore. And when I dropped into England I worked with John Kpaye – there are many I have access to.

That was where the amalgamation started with Sebastian and Martin from Jin Jin. Then later on I went and did a track with Sebastian and Jin Jin in France for his LP. I did two tracks – I did Wild Child then and I did a rough version of Riddim of Life which I didn’t complete – so then we decided to do this LP. Martin laid a number of rhythms and sent them, I took out most of the bass and used Familyman. I had Tyrone Downie come in, I had Chinna and Sticky Thompson do percussion and I had Bongo too. I have always been close to most of the musicians. Like Familyman – me and him go back 40 years. I’ve worked with Leslie and Harold Butler, I’ve worked with Ibo Cooper, Robbie Lyn, some of the better keyboard players in Jamaica. And as for guitarists I don’t even have to call their names – Chinna Smith, Cat Coore. And when I dropped into England I worked with John Kpaye – there are many I have access to.

There was a Serge Gainsbourg cover originally slated to be on the album – what happened to that?

Me and Chinna many years ago used the rhythm for Gainsbourg and I wrote the lyrics for a track called Consider Me. But we were having a bit of a problem because this guy in France loved it so much he took it to Universal for the publishing and they still don’t want to give anything. I don’t even know if it’s on the album or not! I haven’t heard it yet. Martin is supposed to be sending me a copy of it.

What do you think of the horsemeat scandal in the UK that has made world news?

People will try to make money and cut corners in any way. It would be best if one was natural, as in vegetarian, so then they wouldn’t have any problems with meat! (laughs) But it’s money – how to make money in the end – when the demand is too great and you can’t supply then people will do little things out of the way. It’s unfortunate but at the same time give thanks it is not a poison. I heard an English woman say on the radio that during the war they used to eat it but at least they knew what they were eating. It’s less caring of mankind’s welfare because they have to depend on the pharmaceutical companies who make their profits off of your not being well. So they don’t mind if a certain percentage is getting affected, whether it’s meat or whatever kind of food that shouldn’t be given to humans to use. So it suits them to have mankind not too healthy.

Finally, a question from my editor rather than me, but what do you think about Bunny Wailer’s criticisms of Snoop Lion?

Hear me know. I will say this. If you follow the Christian doctrine, Barabas was forgiven on the cross. So if a man has a conversion while on the road and takes a different direction then I have no problem with it. Because each one should find balance – that is our hope for everyone. That is our hope for every human being – to balance the chaos and cosmos and live in a right and correct way. So if Snoop has made that change then all the better for him. As for my brethren’s comments on it I would prefer not to have much to say on that – that’s his opinion.